Scène à Faire: Copyright law's fancy French phrase for "being basic"

The art of being unoriginal.

In this 5-minute read, we'll discuss the scène à faire doctrine, a fancy French phrase from the world of U.S. copyright law. While less well-known to the layperson, it’s already playing a small role in Generative AI copyright litigation. Plus it’s fun to say out loud. Let’s get started!

AI, copyright, and scène à faire

"Scène à faire," is French for "necessary scene." If you don’t speak French, Merriam-Webster has a spoken pronunciation of the phrase on their definition page. In the context of U.S. copyright law, scène à faire refers to a standard or clichéd theme that is commonly found in a particular genre or type of creative work. These generic themes are considered indispensable for conveying specific ideas and are therefore not protected by copyright.

When we consider the five exclusive rights afforded by copyright law, the scène à faire doctrine is principally concerned with the creation of derivative works. This is based on the understanding that certain scenes or elements are so commonplace that they are likely to appear in numerous works across the same genre. To grant an individual author sole rights over such universally depicted scenes would undermine the fundamental goal of copyright law, which is to stimulate, not suppress, creative expression and innovation. (See the “Quick copyright primer” section in “Why AI-generated art can't be copyrighted” for more on copyright basics).

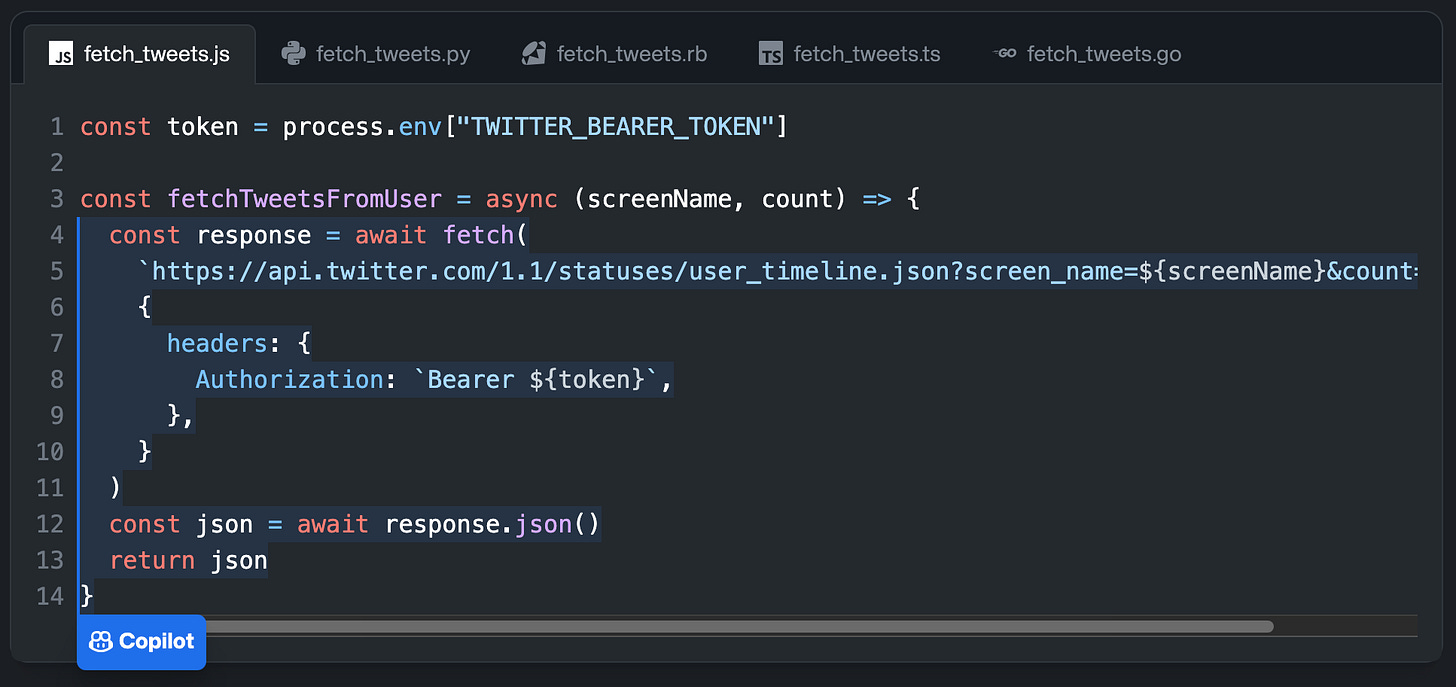

To understand the relevance of scène à faire, let's look at a current ongoing lawsuit in the United States involving several major players in the tech world: Microsoft, GitHub, and OpenAI. The lawsuit pertains to GitHub Copilot, a tool that aids in software development by using AI to generate production-quality code. Microsoft owns GitHub, and OpenAI developed the AI model that powers Copilot (OpenAI is an independent research organization that partners with Microsoft). The plaintiffs in the lawsuit allege that their human-written code was used unlawfully during the AI model's training. This causes Copilot to repeat some of the code snippets in its output, allegedly infringing the plaintiffs’ copyright protection.

In their requests to dismiss the suit (known formally as a “motion to dismiss” in legal parlance), both Microsoft and OpenAI suggested that some code snippets output by Copilot may fall under the doctrine of scène à faire.1 This implies that the companies regard certain Copilot-generated code snippets as constituting widely recognized methods for implementing specific algorithms. Consequently, their argument implies that these snippets, even if they resemble human-written code, should be exempt from copyright violations, being too commonplace to warrant copyright protection.

Quick overview of two famous scène à faire cases

The case Kaplan v. Stock Market Photo Agency showcases the application of the scène à faire doctrine in U.S. copyright law. This case revolved around two similar photos: one taken by Peter Kaplan in 1989, and another taken by Bruno Benvenuto in 1997 (see below). Both images portrayed a man standing on a ledge.

Kaplan argued that Benvenuto's photograph was too similar to his own, alleging copyright infringement. However, the court disagreed. It ruled in favor of Benvenuto, noting, “the situation of a leap from a tall building is standard in the treatment of the topic of the exasperated businessperson in today's fast-paced work environment, especially in New York…”

In essence, the court concluded that a man on a ledge was a “necessary scene” or scène à faire, a standard representation of corporate exasperation. This meant that no single person could monopolize this concept through copyright laws. As a result, Benvenuto's photo, despite its similarities, did not infringe on Kaplan's copyright.

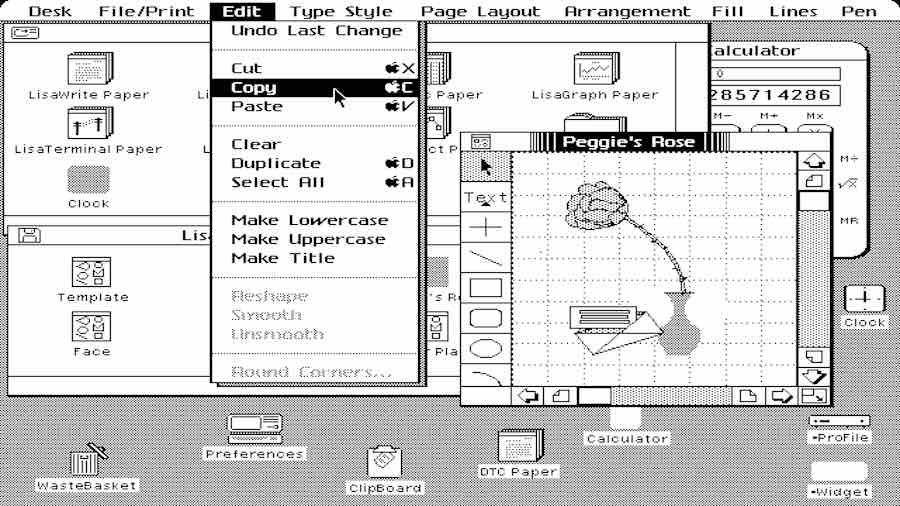

Scène à faire’s impact on the technology sector dates back to a famous 1988 case, Apple Computer, Inc. v. Microsoft Corp. Apple claimed that Microsoft's Windows operating system infringed on the copyright of Apple's Macintosh operating system by copying its visual appearance, including elements such as windows, icons, menus, and the overall "look and feel." The court ruled in favor of Microsoft, stating that most of the elements in Windows that Apple claimed were infringing were scènes à faire. The court found that these elements, like windows, icons, and menus, were common to computer user interfaces (UIs) and necessary for the functioning of a UI-based operating system. To quote the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, “A programmer has only two options for displaying more than one window at a time: either a tiled system, or an overlapping system. As demonstrated by Microsoft's scènes à faire video, overlapping windows have been the clear preference in graphic interfaces.”

Scène à faire and Generative AI

Reflecting on the relevance of scène à faire, some companies might propose its applicability to the output of Generative AI systems in cases of potential copyright infringement, much like Microsoft and OpenAI in their defense of Copilot’s AI-generated code. Consider generative text-to-image AI systems such as Midjourney, which create images based on human-provided prompts. These prompts often describe clichéd or commonplace scenes, which can carry through to the final image. An example is the prompt: “Photo of a man with a beard and glasses in front of a computer screen programming at an office.”

Comparing a Midjourney image generated from this prompt with a similar one from a stock photo service like Shutterstock (as shown below) brings this issue into sharp focus. The images are about as similar as those in the Kaplan case. However, if the photographer of the Shutterstock image were to claim copyright infringement, Midjourney might invoke the scène à faire doctrine in its defense. This same argument could apply to numerous stock images that, by their nature, often depict routine scenes.

Interestingly, a related yet distinct issue is currently being litigated in the U.S., where a class-action lawsuit has been brought against text-to-image technology companies, Stability AI and Midjourney. This case diverges from the main focus of this article in that it centers on the use of copyrighted images for AI training data, rather than the copyrightability of AI-generated output. The plaintiffs accuse these companies of infringing on artists' rights by scraping images from the web for AI model training. At this stage, it remains unclear whether the scène à faire doctrine could serve as a viable defense in this context. Notwithstanding a new legal precedent, claims of scène à faire as protection for use in AI model training would likely be determined on a case-by-case basis.

Pivoting back to AI-generated output, scène à faire could potentially extend beyond images to other types of content. For instance, blues music has a set of standard structures, rhythms, and chord progressions, as do many other musical genres. Thus, the output from an AI music-generation system might be argued to be partially shielded from copyright violations through scène à faire.

Nevertheless, these legal theories remain largely untested, and future case law will be needed to clarify the boundaries and applications of the scène à faire doctrine in the context of AI-generated content.

Broader implications of scène à faire in AI applications

The potential reach of the scène à faire doctrine extends beyond text-to-image AI systems and AI-generated music. In video games, AI-generated assets, such as character models or environmental designs, could draw upon standard or clichéd themes that could fall under scène à faire. Similarly, as AI evolves in its ability to generate narrative content, we might see a more nuanced application of this doctrine in film and television, where standard scenes or plot points could be considered as scène à faire. Again, however, the application of scène à faire to these diverse AI scenarios remains largely unexplored in court, underscoring the need for future legal precedents to clarify its boundaries and applications in the context of AI.

In Microsoft’s motion to dismiss, they write: “Even when a snippet matches training data, there are a host of additional hurdles to the notion that any particular Output would result in copyright infringement: the copyrightability of such material in light of doctrines of merger and scènes à faire…”

OpenAI’s motion states: “Here, Plaintiffs have not alleged facts sufficient to establish a substantial risk that any copyright infringement has occurred or that any future infringement is likely because of the removal of CMI [Copyright Management Information], nor that any of the OpenAI Entities had reason to know of any such likelihood. They have not alleged, for example, copying of protectible expression: that is, that the allegedly copied code was original, that there was no merger of idea and expression, and that the allegedly copied code did not represent ‘scènes à faire.’”