Why AI-generated art can't be copyrighted

An explainer on the current legal landscape of AI-generated content and possible policy options

The 30-second summary

In most countries, copyright protection is typically restricted to creative works that have been authored by a human. However, copyright law recognizes the use of computers and AI as tools in the creative process.

As a result, under current laws, AI-generated content is generally not eligible for copyright protection, while works involving AI assistance may qualify. For example, if unaltered images generated by text-to-image tools like Midjourney are published or distributed, they are typically considered AI-generated content and do not qualify for copyright protection. Such works would enter the public domain and become available for unrestricted use. On the other hand, works that merely use AI assistance — such as when an author includes Midjourney images in a larger project like a children's book with human-written text — are more likely to meet the requirements for copyright protection.

When exploring possible legal reforms to address the copyright implications of AI-generated content, four main policy options have been considered:

Keep AI-generated content in the public domain

Establish AI as an “electronic person”

Create specialized laws specifically for AI-generated content

Designate a human author for AI-generated content

The full article

Welcome to this 25-minute read on the copyright status of AI-generated output! If you do not like long-form content, this is not the article for you. Go watch some Tiktok videos instead.1

The goal of this article is to provide an explainer approachable enough for a novice, but with bits of novelty for the experts. It also aims to be technically accurate, globally comprehensive, practical, up-to-date, and include helpful visuals, all while being only a little bit boring. I promise you we can do it! By the end of this article you will know as much about this topic as a bad lawyer. Maybe even a good one!

While the primary focus will be on AI-generated images, rest assured that many of the lessons can be applied to other types of AI-generated content.

Nothing in this article constitutes legal advice.

Overview and what’s at stake

Before we delve into the specifics of AI output and copyright law, let's begin by quickly covering the essentials of copyright law and why the debate surrounding the copyright status of AI-generated content is significant.

I will initially use the generic term “AI-generated” for all AI output, but we’ll discuss the importance of the “AI-generated” vs. “AI-assisted” classification below.

What’s at stake?

The art world was forever changed in 2018 when an AI-generated portrait sold at Christie's New York for a staggering $432,500. Since then, AI-generated art has experienced profound advancements, as evidenced by the remarkable progress of platforms like Midjourney. These groundbreaking AI advancements raise not only eyebrows but also legal questions. Who owns the rights to a work of art produced by an algorithm? How can the originality and creativity of such a work be assessed? And what are the implications for the future of art and culture? In this section, we’ll briefly explore what’s at stake for artists, companies, and society at large.

The copyright status of AI-generated works carries significant implications for creativity and innovation. The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) sums up the stakes involved in this discussion, highlighting two contrasting perspectives:

If AI-generated works were excluded from eligibility for copyright protection, the copyright system would be seen as an instrument for encouraging and favoring the dignity of human creativity over machine creativity.

If copyright protection were accorded to AI-generated works, the copyright system would tend to be seen as an instrument favoring the availability for the consumer of the largest number of creative works and of placing an equal value on human and machine creativity.

Building upon the WIPO statement, seven key areas of focus arise. Many of these focus areas will be discussed further throughout this article.

Economic Significance: The determination of ownership and legal protection for AI-generated content directly impacts the financial beneficiaries, ensuring fair distribution of economic benefits derived from its use.

Enhancing Competitiveness: Clear legal guidelines regarding AI-generated content foster a competitive environment by preventing unauthorized use or theft, safeguarding the interests of creators, and promoting a level playing field that encourages investment in AI research and development.

Driving Innovation: Establishing legal clarity for AI-generated content stimulates innovation in AI technologies, creating an environment that supports creators as well as AI developers.

Legal Clarity and Guidance: Resolving the copyright status of AI-generated content provides clear guidance for AI developers and users, assisting them in effectively navigating legal frameworks and avoiding legal ambiguities or risks.

Legal Precedents: The way copyright issues surrounding AI-generated content are addressed can set important precedents for other legal aspects related to AI, such as liability and accountability.

Industry Impact: Legal clarity surrounding AI-generated content minimizes disruptions in industries that rely on creative outputs, fostering stability and providing creators with confidence about how AI-generated content can and can’t be used.

Ethical Queries: The copyright status of AI-generated works sparks thought-provoking discussions on the nature of creativity, authorship, and the role of machines in artistic and intellectual endeavors. Exploring the ethical implications helps society navigate the evolving relationship between human and machine creativity and determine the value placed on each.

Practical Implications: The Microsoft Example

To further understand the practical implications of the copyright status of AI-generated works, imagine a scenario where technology firm Microsoft used an unaltered AI-generated “banner image” in a U.S.-based online holiday marketing campaign. (For instance, an image similar to the one below I created using Adobe Firefly). Since AI-generated content is not currently copyrightable in the United States, from a purely copyright law perspective it is possible that a competitor or other person or entity could take that image and use it for their own marketing campaign.

There are nuances. The “borrower” could not confuse consumers by keeping an affixed Microsoft logo on the image (trademark law) or by otherwise acting as if the campaign were from Microsoft (unfair business practices law). But the image itself would be fair game.

Likewise, consider an independent author who incorporates AI-generated images into a children's book. There’s a possibility that others could use the same AI-generated images for their own projects without infringing copyright laws. This raises concerns for independent authors who rely on the uniqueness and originality of their works.

Quick copyright primer

Copyright law exists to help protect “the fruits of mental labor” by providing a limited market monopoly for creators.2 This enables creators to reap financial benefits from their work, thereby fostering a thriving creative ecosystem that contributes to the enrichment of culture and the advancement of science for the benefit of the public.3

Examples of copyrightable material include photographs, literary works, computer software, video games, digital art, drawings, sculptures, paintings, plays, and music.4 These expressive creations are commonly referred to as “works,” as in “a photograph is a copyrightable work” or “all 100 of the artist’s works are under copyright.” Regardless of their medium, whether it be writing, painting, sculpting, or computer programming, those who bring these creations to life are called “authors.”

Although specifics vary by country, generally speaking copyright protection offers authors five exclusive rights for their creative works:5

Reproduction: The right to make copies of a protected work.

Distribution: The right to sell or otherwise distribute copies to the public.

Adaptation: The right to prepare new works based on the protected work, for example creating a film based on a novel.

Performance: The right to perform a protected work, for example a play.

Display: The right to display a work in public, for example in an art gallery.

There are some exceptions to these exclusive rights, such as the “fair use” clause in the United States and “fair dealing” in common law jurisdictions, the details of which are not so important for this article (but are very important for other AI copyright questions).6

The duration of copyright protection varies across countries, but a common standard is the life of the author plus 50 years.7 This timeframe ensures that the author can enjoy the benefits of their work during their lifetime and allows their estate and beneficiaries to continue reaping the benefits for a period after their death.

A basic tenet of copyright law is the so-called “idea-expression dichotomy” which states that expressions are copyrightable, but ideas are not. To illustrate this concept, consider the example of pitching a movie centered around a gangster in 1860s New York. The idea itself is not subject to copyright protection. However, when a movie studio creates a specific expression of that idea, such as the film "Gangs of New York," it becomes eligible for copyright protection.

Copyright law generally allows for the usage of tools by creators, for instance a digital artist may use Adobe Illustrator to create a piece of digital art (more on tool use later). Copyright is granted automatically once a work is “fixed” in a medium of expression (ex. digital art is fixed on a hard drive), though it is usually also possible to explicitly register a work with a country’s copyright office (more on that later too). Copyright falls under the umbrella of Intellectual Property Law (IP); other areas of IP law protect inventions (patent law), marks, slogans, and company names (trademark law), and business secrets (trade secret law).

Adjacent bodies of law

While the scope of this article is confined to a discussion of AI output, there are adjacent areas of law that are worth mentioning in brief:

The larger body of intellectual property (IP) law, including the totality of copyright law, but also trademark, patent, and trade secret law.

So-called “related rights.” These are rights that are adjacent to the copyright law that protects authors. Examples include the right for a broadcaster to record, distribute, and rebroadcast a sporting event despite the fact that the event itself cannot be copyrighted or the right for a musician to perform a song she did not write. Related rights could play a role in AI copyright law if they are extended to include the training of AI models or creation of AI-generated content. Such extensions have been proposed.8

Sui generis rights. The term “sui generis rights” is a fancy phrase that simply means “a special, stand alone law.” You can pronounce it like this. In IP law sui generis rights have been enacted to extend protection to areas not covered by traditional statutes. Examples of sui generis rights include integrated circuit layouts, ship hull designs, fashion designs, databases, and plant varieties. Sui generis rights in copyright law are more or less synonymous with related rights. Both will be discussed more in the “Policy options” section.

Safe harbor protections for service providers that administer open platforms where users post content. For example, DMCA provisions in the United States protect YouTube if users upload copyrighted videos as long as YouTube abides by certain provisions such as administering take-down notices. Since AI-generated content is unlikely to qualify for copyright protection in many jurisdictions, including the United States, it will be interesting to observe how safe harbor protections end up intersecting with AI-generated content (or not).

Limited civil liability for internet platforms where users may post content. An example in the United States is Section 230 which provides some protection for social media companies and other online platforms against posting of objectionable content by users. Regulators in the United States have already said that Section 230 will not apply to AI output, however they were referring to content generated by the platforms themselves (ex. Bing Chat). It’s unclear if AI-generated content initiated by users and posted to internet platforms will have differential liability treatment to that of today’s non-AI content. Generally speaking AI liability is an area to watch, but outside the scope of this article.

Laws around unfair business practices. For example, laws against confusing customers, such as an art gallery selling tickets to an exhibit including AI-generated images but implying in promotional material that the images were human-generated.

The right to publicity, which is the right to protect one’s name and likeness from unauthorized commercial uses. For instance, laws against a poster company selling posters of an AI-generated LeBron James without his authorization.

The copyright status of AI-generated content is clearly not the only legal issue of note. The inverse question is equally relevant: can AI-generated output itself violate copyright protection of an existing work? If so, should AI platforms be required to proactively implement measures to restrict the probability of copyright-infringing AI-generated content? What tradeoffs will this induce in terms content quality and usability? What responsibility do users of the tools have? Whatever the answers to these and other questions we can expect more AI-focused legislation soon.

As a practical example, Stability AI has been known to output images that include a Getty Images watermark (see example below via Peter Henderson), suggesting Stability AI used Getty Images during the model training of their text-to-image technology. Getty has an ongoing lawsuit against Stability AI.

As the above image suggests, another primary concern among many is the legal authorization (or lack thereof) of companies using copyrighted art to train AI models. This will be discussed in a future article.

But to return to the primary question at hand, can AI-generated content be copyrighted? The current answer is "probably not" in many jurisdictions around the world, with some exceptions and complications we will discuss. Let’s learn more…

Two important copyright cases

Two pivotal copyright cases separated by over a century — one adjudicated in the United States and one in the European Union — have become among the most highly cited in preliminary legal discourse concerning the prospective copyright status of AI-generated works.9 Intriguingly, both cases concern the authorial choices made in two well-known portrait photographs.

Legal disputes around portraiture might seem an odd source of insight into the copyright implications of AI-generated content, but the cases' impact has already begun to extend beyond academic theorizing; as we'll discuss more later, the U.S. case was invoked in a recent governmental ruling on the copyright status of AI output. Together the cases underscore the necessity of human authorship in order to secure copyright protection, but they also illustrate that authors are allowed technological aids in the production of their creative output (in both instances, this aid was a camera).

The United States case, Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. V. Sarony, was argued before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1884. In this case Burrow-Giles Lithographic Company made unauthorized lithographs of an 1882 photograph of noted author and poet Oscar Wilde taken by photographer Napoleon Sarony. Burrow-Giles argued that photographs were mere mechanical reproductions of the physical world and therefore should not qualify as an act of authorship, negating copyright protection.

The Supreme Court, however, found that Sarony's photograph was protected by existing U.S. copyright law, noting that Sarony carefully arranged the setting and design of the photograph, thereby creating a "[G]raceful picture...entirely from his own original mental conception." By doing so Sarony acted as the “mastermind” of the photo. This passage, along with several others from the Court's opinion, make it clear that for the purposes of U.S. copyright law authorship is a purely human endeavor.

Additionally, the decision clarifies that a camera is a perfectly acceptable technological aid through which an author can express their originality and creativity, implicitly opening the door for the usage of more advanced technological aids in the future. Importantly, the Court noted that if a particular photograph were merely a mechanical reproduction of the physical world, because it lacked sufficient human creativity in its conception, that it may not qualify for copyright protection. (However, note that in the United States only a "modicum of creativity" is needed).

The second case, Eva-Maria Painer v Standard VerlagsGmbH, occurred in the European Union in 2011. The case concerned portrait photographs taken by Painer and published without authorization in several newspapers and magazines in Austria and Germany. The photographs themselves were of Natascha Kampusch, a young girl who had been abducted. Painer had, by happenstance, photographed the girl several years prior. In their defense the publishers made an argument quite similar to that of Burrow-Giles nearly 130 years earlier: that because in portraiture the photographic subject is predetermined, "the creator enjoys only a small degree of individual formative freedom" which is not sufficient to achieve copyright protection.

However, the court disagreed, noting that even in portraiture a photographer can make creative choices such as the setting, background, and camera angle. The court referred to an existing EU regulation, which states that, "only human creations are therefore protected, which can also include those for which the person employs a technical aid, such as a camera." Like the Burrow-Giles case in the United States this EU case underscores the requirement of a human author and the permissibility of technology usage in creative output.

Let's now jump forward to the present day and investigate the copyright status of AI-generated content in the U.S. and EU more deeply.

Copyright laws regarding AI-generated works in the United States

Focusing first on the United States, in a recent correspondence from the U.S. Copyright Office to Kristina Kashtanova the office reiterated that AI-generated works do not qualify for copyright protection as they do not constitute human authorship.

Kashtanova filed for copyright protection for her comic book Zarya of the Dawn which included a collection of images created by text-to-image platform Midjourney.

The Copyright Office based its decision on U.S. copyright law and relevant Federal and Supreme Court precedents, including extensive references to Burrow-Giles. United State Code dictates that to qualify for copyright protection, a work must meet three criteria as outlined in 17 U.S.C. § 102(a). The work must be:

Original

A work of authorship

Fixed in a tangible medium of expression

Given that Midjourney's output is inherently "fixed" in computer memory, it naturally fulfills criterion 3. However, the Copyright Office disputed whether the images satisfied the originality and authorship criteria.

The Midjourney images were not deemed to be original because Midjourney’s image creation process is “merely mechanical.” Midjourney was trained to transform a “field of visual ‘noise’” into a coherent image. Although the process involves user prompts, there is also a significant random component. (For those that are interested in the details I recommend this video from the wonderful Computerphile YouTube channel).

Furthermore, the Midjourney images were not recognized as a work of authorship because Kashtanova was not deemed the “mastermind” behind the work. In contrast to the camera in the Burrow-Giles case, the Copyright Office viewed Midjourney as more than just a technological aid for human creativity.

This opinion echos back to the idea-expression dichotomy. A prompt is an idea for an image, but the image itself is the expression of that idea. In the context of Midjourney, the Office perceives the expression as originating from the AI platform rather than the human user.

The Office's rejection of copyright for images in Kashtanova’s comic book is in line with their existing compendium where they note that, “the Office will not register works produced by a machine or mere mechanical process that operates randomly or automatically without any creative input or intervention from a human author.”

The Office did grant copyright protection for the text appearing in Zarya of the Dawn as it was written by Kashtanova. They also granted protection for the specific arrangement of the images and text as that was also Kashtanova’s production. This means it would not violate copyright law for a different individual to use images from Zarya of the Dawn as long as the way the images were arranged was unique.

Additionally, the office did not preclude the fact that in the future AI-generated images may qualify for copyright: “It is possible that other AI offerings that can generate expressive material operate differently than Midjourney does.”

Furthermore, the Office has also launched an initiative to examine the copyright law and policy issues raised by artificial intelligence (AI) technology.

It’s worth noting that a roughly similar dispute arose during the onset of video games in the late 1980s. In Atari Games Corp v. Oman video game company Atari filed for copyright protection for their arcade game Breakout — developed by Apple founders Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak — twice, but were denied copyright registration on both occasions. In their rejection the U.S. Copyright Office noted the game’s lack of sufficient creativity to qualify for protection. Not until the decision was successfully appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, who at that time had Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg presiding, did the Copyright Office finally accede to the game’s copyright registration.10

While copyright law is statutory in nature, a substantial body of case law has also been built up. Generative AI technologies are sufficiently new as to not have had their day in court; it could be that future legal decisions shift the way copyright law is thought about and applied to AI-generated works. However, this brings up one important difference of note between the Atari case and Kashtanova’s: by the mid-1980s the U.S. Supreme Court had already created a precedent that video games qualified for copyright protection.11

The distinction between AI-generated and AI-assisted works

The discussion surrounding AI copyright law in the United States highlights a key distinction: whether a specific work is categorized as “AI-assisted” or “AI-generated.”12 This distinction has gone by various names in AI-centered legal discourse; for instance the concept of "computer-generated" works in UK law, the “computer-assisted works” vs. “autonomously-generated works” distinction in analysis of Australian copyright law,13 or the notion of “purely computer-generated works” in the EU context.14

While there are no universally agreed-upon definitions distinguishing the two concepts, the dichotomy clearly strikes at the heart of AI copyright law: is a work involving AI driven by human creativity (AI-assisted) or purely mechanical in nature (AI-generated)? Under current copyright laws AI-assisted content may be found to be copyrightable if it includes a sufficient amount of human-backed originality and creativity, whereas purely AI-generated work is likely to fall outside of copyright protection.

This is exactly the U.S. Copyright Office’s stance in the Kashtanova’s case. The Office denied copyright for images produced using Midjourney; noting the works were fully AI-generated. But the office allowed copyright protection for Kashtanova’s comic book as a whole, which included both AI-generated images and human-written text and arrangement, implying that when the comic book was taken in full it was merely AI-assisted (though they did not use that language).

Nevertheless, not everyone agrees with maintaining the AI-assisted vs. AI-generated dichotomy. Legal scholar Robert Denicola has criticized the practicality of making such categorizations, asserting that they involve impossible distinctions. Instead, Denicola proposes assigning rights for AI output to the user, an idea that will be further discussed in the “Policy options” section.

The rise of Generative AI features in popular photo-editing software, including Adobe Photoshop and other tools, lends support to Denicola's viewpoint. As these features become more prevalent, the line separating AI-assisted and AI-generated works will further blur. A significant portion of visual creative output, including the multitude of images captured on mobile phones, will soon incorporate Generative AI elements. It will become increasingly difficult to track the extent of Generative AI involvement within a specific image, especially as different Generative AI features are combined or integrated into features that no longer carry the “AI” label.15 Creators themselves may struggle to quantify the precise combination of AI and human originality, losing track of the specific steps taken to achieve the final output.

This trend extends beyond visual media; Generative AI is also making its way into writing assistance tools like SudoWrite and productivity software like Microsoft Office and Google Workspace.

As this trend continues, the distinction between AI-assisted and AI-generated works may become increasingly irrelevant, as it becomes more challenging to determine the necessary level of human control required to achieve AI-assisted status and thus meet the copyright threshold.

Two AI cases in China

Two cases decided in China in 2020 help further exemplify the complexity at play in the “AI-assisted” vs. “AI-generated” distinction.

In one case the Beijing Internet Court found that an AI platform that accepted a set of keywords and used them to produce an automated report did not qualify for copyright protection. The court determined that neither the software developer nor the software user could be considered the author of the report because they did not create or generate its content. As a result, since the report was not the product of a natural person, it did not qualify for copyright protection.

A second case involved Tencent's "Dreamwriter" AI platform capable of automatically publishing online articles (the case specifically involved an article it published related to the stock market). The article was affixed with a notation that it was AI-generated. Upon seeing this notation Yinxun copied the article and published it on their own site, at which point Tencent sued. This time the Shenzhen Nanshan District People’s Court found the article did qualify for copyright protection due to a series of human decisions needed to configure Dreamwriter to allow for its automated publishing. These human decisions guiding the AI platform qualified as a sufficient amount of human-driven creativity.

Copyright laws regarding AI-generated works in the European Union

Copyright protection for AI-generated images is not likely to be available in other parts of the world either. The Berne Convention, which sets minimum standards for copyright protection for its signatories (most countries in the world), has a decidedly humanist stance. For instance, as suggested earlier when discussing the term of copyright protection, the convention uses the phrase "the life of the author," implying that the author must be a human being.

In the European Union (EU) a set of directives have been issued which provide further copyright guidance to member states. These directives form the foundation of what’s called the EU copyright acquis, the regulatory copyright framework in the EU. While these directives do not strictly require a human author it is clear from the initial directive proposals, created in the lead-up to enacting the directives, that human authorship was assumed.16 Likewise, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), the chief judicial authority in the EU, has built up a body of EU case law by interpreting these directives. As Painer demonstrates this case law also assumes a human author. Additionally, many EU country-specific laws underscore the human-centered notion of copyright. For example the Spanish Law on Intellectual Property notes the law applies to, "[T]he one who performs the purely human and personal task of creating the work..."

In the context of the Berne Convention's emphasis on human authorship, Jane Ginsburg offered an analogy to the physical world which illuminates why using Generative AI tools does not confer copyright protection. Clicking a “Generate” button or providing a text description of a scene does not inherently make one an author:

Offline, merely giving a command does not make one an “author”: Pope Julius II may have commissioned the painting of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel; from a Berne perspective (at the very least), the author of the frescos remains Michelangelo.

However, that viewpoint is not universally accepted as we’ll see later in the “Policy options” section.

To summarize the legal framework in the EU, the Berne Convention sets minimum requirements for copyright law for signatories, which includes EU member states. EU directives layer on additional copyright guidelines for member states on top of the Berne Convention. EU member state laws implement The Berne Convention requirements and EU directives, adding or extending regulations if desired. Though note that at each level there are exceptions available and flexibility in legal interpretation. If there are copyright disputes between countries or a country has not correctly implemented EU law, cases can be brought to the CJEU. Currently, all three levels of legal jurisdiction as well as the CJEU suggest a human author is necessary for copyright law enforcement. (For a more thorough description of the EU legal framework see Footnote 17).17

On 14 June 2023 The EU Parliament passed the AI Act. Talks will now begin with EU countries on the final form of the law. The Act does not explicitly establish regulations around the copyright status of AI-generated works (likewise for AI-assisted works). However, given the sensitivities called out in the act around foundation model providers and data used for model training, it seems likely that future EU copyright regulations enacted by Parliament would be in line with the limited scope outlined in this section.

Five steps to determine copyright status of AI works

The necessity of human authorship can be further examined by leveraging a 2021 EU Commission report, “Trends and Developments in Artificial Intelligence,” which outlined AI challenges to the intellectual property rights framework. Based on an analysis of the Berne Convention, the EU copyright acquis, and case law from the CJEU (including Painer) the report outlined a five-step test to determine whether an AI output qualifies for copyright protection:

Step 1: Determine if the work is in one of the three domains protected by copyright (literary, scientific, or artistic).

Step 2: Asses the level of human intellectual effort needed to create the work.

Step 3: Weigh the space available for human originality and creativity against the automation provided by the AI system.

Step 4. Appraise the level of human expression in the final product.

Step 5. Qualitatively assess the results from Steps 1 to 4 and make a final ruling.

Let’s briefly discuss each step:

Step 1: Determine if the AI work is in one of the three domains protected by copyright (literary, scientific, or artistic).

It is likely that AI output easily meets the requirement of falling within a protected domain. For instance, Midjourney images clearly fall into the domain of artistic output as do literary works from ChatGPT and other Large Language Models. ML models or GPT-generated code could be considered scientific output.

Step 2: Asses the level of human intellectual effort needed to create the work.

Currently, human effort is required in all AI outputs. Even in platforms like Midjourney, where AI can fully generate images, human prompts are needed to initiate and guide the system. However, so-called “prompt engineering” may not qualify as a sufficient amount of human intellectual effort.18

On the other hand, for some projects, AI output is just one part of the creative process. As we saw in Kashtanova’s comic book example, Midjourney images were paired with human curation, arrangement, and prose. This leads us to Step 3.

Step 3: Weigh the space available for human originality and creativity against the automation provided by the AI system.

Let's delve deeper into Step 3, as it carries substantial weight in this discussion. This step acts as a conduit, transforming human intellectual effort (Step 2) into human expression (Step 4) by injecting human originality and creativity. Step 3 therefore emerges as the linchpin in assessing possible copyright protection: there is no room for originality if human agency is suppressed by tools that automate the entirety of the creative process.

Step 3 is further broken into three distinct phases of the creative process:

“Conception” of a creative work.

“Execution” in creating the work.

“Refinement” of intermediate outputs to arrive at the final product (called “redaction” in the report).

These three steps represent the process by which an idea is transformed into an expression.

There is no precise recipe of human involvement needed across the three phases to meet the requirements of creative freedom. Human involvement in one phase of the creative process may be sufficient, but more is likely better.

The conception phase

The EU Commission report notes the following about conception:

The conception phase involves creating and elaborating the design or plan of a work. This phase goes beyond merely formulating the general idea for a work. It requires a series of fairly detailed design choices on the part of the creator: choice of genre, style, technique, materials, medium, format, et cetera.

These previsualization steps are exactly what “Midjourney artists,” if I can use that term, claim as their process while prompt planning. Consider, for example, the 10 attributes in Midjourney artist Nick St. Pierre’s Additive Prompt Framework: General style, composition, medium, film type, subject description, subject styling, environment, lighting, atmosphere, and mood.

This process leads St. Pierre to create fairly complex prompts:

Editorial style side-view medium-full photo shot on Fujifilm Pro 400H of a 40-year-old Greek man with short gray hair & full beard pondering a masterpiece in a Musée d'Orsay Gallery. He's wearing a blue jacquard blazer by Ferragamo with a white button-up. The soft gallery lighting and careful composition evoke a sense of refined luxury and creative curiosity as he gazes fixedly at the magnificent painting in front of him.

The above prompt resulted in the image below. We’ll revisit this image in a moment.

However, the very nature of art makes it impossible to establish a single, universally accepted description for a given image. Consequently, AI image-generation models output one specific visual portrayal based on the semantic associations underlying their text-image training data. But this AI-generated portrayal may differ from an individual’s intended visual representation when attempting to convey their emotions and thoughts through language.19 That brings us to the execution phase…

The execution phase

Even if an individual has previsualized an intended output and is capable of translating their conception into a written description the blackbox nature of text-to-image systems obscure the method by which that description is realized.

There are reasons to question the level of human creative control in current text-to-image systems. As an illustration let’s discuss four limitations of the current state-of-the art text-to-image platform, Midjourney Version 5.1.20

Midjourney is not a “blank canvas” upon which creatives write prompts to control or “build up” images from scratch. Even single-word Midjourney prompts produce incredibly vivid and imaginative images. For example, the set of four images below was generated from the single-word prompt “hat.” See my previous article for many more examples.

There are numerous classes of so-called “antagonistic prompts,” which expose the ways in which Midjourney’s semantic understanding differs from that of a human. The prototypical example is from McCormack et al.’s 2023 research paper, “Is Writing Prompts Really Making Art?” The paper demonstrates that a prompt requesting a horse riding an astronaut produces much the same result as a prompt for an astronaut riding a horse.

Although the specific mechanism by which Midjourney creates images is random, there are surprising motifs which the platform mysteriously repeats. My favorite of these is “The Midjourney Bearded Man” in which prompts describing a man with a beard routinely create images of the same bearded man.

Writing complex prompts — like those generated by following Nick St. Pierre’s prompt system above — does not seem to systematically produce more compliant Midjourney output. In the comparison below, the original effusive prompt from St. Pierre did not appear to steer Midjourney’s output more fruitfully than a sparser, less poetic prompt (“Medium prompt”). Even a quite simple prompt produced desirable results, with the main difference being the age of the man and jacket material, but not the background, lighting, sophistication, or general style.

These examples collectively highlight the difficulty in asserting extensive human control over the output generated by Midjourney, thus demonstrating the limitations in establishing a significant degree of human originality during the execution phase.

The refinement phase

The refinement phase, often overlooked but crucial in the creative process, deserves recognition. Although AI models are starting to possess the ability to evaluate and enhance their own output, humans currently play a significant role in refinement. The degree of refinement applied to an AI output is likely to affect its eligibility for copyright protection. Extensive alterations made to an AI output using tools like Photoshop or other imaging software may be considered sufficient as they transform the visual characteristics of the original AI-generated work. On the other hand, minor refinements, such as merely selecting the best output from a series of AI-generated images, would be deemed insufficient (see the discussion of the Kristina Kashtanova case in the United States as an example).

Step 4: Appraise the level of human expression in the final product.

The degree of human expression that emerges in a final AI output is based on a combination of the three phases outlined in Step 3. As the EU report notes, from a copyright protection point of view what is important is that the “output stays within the ambit of the author’s general authorial intent.” However, machine learning and artificial intelligence models rely heavily on neural network architectures which are of a “black box” nature, obscuring the precise mechanism by which human input transfigures into machine output. For that reason it’s difficult to fully comprehend how intended expression in the conception phase is carried through to AI output in the execution phase. In contrast, it may be easier to grasp the effect of human expression in the refinement phase, especially if it involves a human performing non-AI steps which are more transparent in their operation.

One area of research that holds promise, albeit still speculative, is gaining a better understanding of how text-to-image systems translate human prompts (text tokens) into image output. OpenAI's recent research provides a potential pathway in this direction. Researchers at the company utilized GPT-4 to explain the functionality of each neuron in the multi-layer neural network architecture of the earlier GPT-2 model (see image below). While there are limitations to this initial research, their analysis suggests that the latent space within the GPT-2 neural network exhibits a discernible and coherent structure.

If similar investigations are conducted on text-to-image models, it could shed light on how human prompts influence AI-generated images. This exploration would contribute to our comprehension of the interplay between human conception and the resulting expressive output. If particular words and phrases are shown to be coherently interpreted by the model and result in consistent artistic depictions then Midjourney and other AI platforms might be considered a steerable tool, the same way Adobe Photoshop is via its GUI. This might support an argument for human copyright of AI-generated images. However, the Midjourney experiments outlined above suggest that current model output is dominated by pre-determined patterns in training data and so technological updates themselves may need to accompany model interpretability in order to fully chart a path toward copyright protection for AI-generated images.

Step 5: Qualitatively assess the results from Steps 1 to 4 and make a final ruling.

While every output must be judged on its own merits, Kristina Kashtanova’s case in the United States paints a picture of how EU courts and regulators may treat AI-generated content. While not explicitly discussing the EU’s three phases from Step 3, the U.S. Copyright Office nonetheless followed similar logic, rejecting copyright protection for the execution phase (the AI-generated images), but allowing copyright for Kashtanova’s final product due to her original conception and the refinement need to produce the end comic book.

Ultimately, based on current laws, it is likely that systems like Midjourney restrict human expression to a degree that may not meet the criteria for EU copyright protection unless the refinement phase sufficiently incorporates human originality. The EU report’s video game analogy is apt:

Even if the player feels empowered and “in control” of whatever transpires on the computer screen, they have no control over the creative process, and their choices do not amount to creative acts justifying a claim of authorship.

This distinction again echos back to the AI-generated vs. AI-assisted discussion. AI-generated works would imply heavy AI involvement in the execution phase of Step 3, whereas AI-assisted works would imply human direction during the refinement phase.

Special legal status for AI?

To reiterate, the discussion thus far assumes that only humans are capable of producing copyrightable output. But is that an inevitability?

Interestingly, special legal status for autonomous non-human agents has been considered in the EU. In 2015 the European Parliament's Committee on Legal Affairs (abbreviated as JURI) set up a working group to provide a report on robotics and artificial intelligence. In the report the group set forth a set of recommendations. Among these was the possibility of:

[C]reating a specific legal status for robots, so that at least the most sophisticated autonomous robots could be established as having the status of electronic persons with specific rights and obligations, including that of making good any damage they may cause, and applying electronic personality to cases where robots make smart autonomous decisions or otherwise interact with third parties independently.

(Here the word "personality" refers to one of the theoretical foundations of European copyright law: the notion that, "Intellectual products are manifestations or extensions of the personalities of their creators.")

JURI also commissioned the EU's Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs to provide a follow-up study on the original report. The study firmly rejected the original report's suggestion that a new legal status of "electronic person" might be warranted for autonomous robots and artificially intelligent agents:

In reality, advocates of the legal personality option have a fanciful vision of the robot, inspired by science-fiction novels and cinema. They view the robot — particularly if it is classified as smart and is humanoid — as a genuine thinking artificial creation, humanity’s alter ego. We believe it would be inappropriate and out-of-place not only to recognise the existence of an electronic person but to even create any such legal personality. Doing so risks not only assigning rights and obligations to what is just a tool, but also tearing down the boundaries between man and machine, blurring the lines between the living and the inert, the human and the inhuman. Moreover, creating a new type of person — an electronic person — sends a strong signal which could not only reignite the fear of artificial beings but also call into question Europe’s humanist foundations. Assigning person status to a nonliving, non-conscious entity would therefore be an error since, in the end, humankind would likely be demoted to the rank of a machine. Robots should serve humanity and should have no other role, except in the realms of science-fiction.

Australia

Copyright considerations in Australia share similarities with those in the U.S. and EU,21 with the AI-assisted vs. AI-generated distinction again being important (Australian legal scholar Jani McCutcheon calls this the “computer-assisted works” vs. “autonomously-generated works” distinction).

In Australian copyright law, authorship is contingent upon a minimum level of “intellectual effort” in the creation or materialization of the final output. However, McCutcheon notes that, “it will be difficult ascribing authorial status to any individual where software substantially determines the shape of a work.”

Applying the analysis framework used in the EU jurisdiction to Australian law, while there is some mental effort involved in the previsualization phase prior to AI image generation, the work's ultimate form is determined during the execution phase and therefore lies with the AI system rather than the human. Consequently, AI-generated images are likely to be considered devoid of authorship in Australia, rendering them ineligible for copyright protection.

The UK and other common law countries

The UK's Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 includes a noteworthy provision that defines computer-generated work. According to the Act, a work is considered "computer-generated" if it is generated solely by a computer without any human author involved in its creation. In situations where a work is indeed computer-generated, such as in the case of AI-generated works, and therefore lacks a human author, the Act stipulates that, "the author shall be taken to be the person who undertakes the necessary arrangements for the creation of the work." While laws in Australia are distinct, many other common law countries have followed the lead of the UK including Hong Kong, India, Ireland, Singapore, and New Zealand.22

There is a debate regarding whether the necessary arrangements copyright paradigm could serve as a model for other jurisdictions worldwide. While some argue in favor of this approach, suggesting its potential as a way forward, other legal scholars challenge its suitability.23 It is worth noting that only a single prominent case in the UK has referenced the necessary arrangements concept, and it does not provide substantial clarity on its application to AI-generated works. Expanding the UK model as a policy option will be discussed in the “Policy options” section.

AI copyright in other countries

While this article has examined various jurisdictions and their approaches to the copyright status of AI-generated works, it is worth noting that information regarding this matter in many other countries is limited. However, given that the majority of countries are signatories to the Berne Convention, it can be presumed that the requirement of a human author, as outlined in the EU section, would also apply.

There is one notable research article that discusses the requirement of a human author in the context of Nigeria and South Africa. Caroline Ncube and Desmond Oriakhogba explore the legal implications of the famous monkey selfie case, in which British nature photographer David Slater claimed ownership of a photograph taken by a macaque monkey using his camera equipment in Indonesia. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) sued Slater's U.S.-based book publisher, arguing that the monkey should own the copyright as the photographer. However, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled in favor of Slater, determining that animals do not have the legal authority to hold copyright claims. Ncube and Oriakhogba analyze the concepts of authorship and ownership under the copyright laws of Nigeria and South Africa and conclude that if the case had been brought before the courts in those countries, they would likely have reached a similar outcome to the U.S. courts. It is reasonable to assume that if non-human animals are not recognized as authors in Nigeria and South Africa, the same reasoning would apply to AI-generated works.

Moral rights

Before delving into AI copyright policy options, it is worth briefly addressing a set of protections known as “moral rights” that are recognized in some countries. While the term may initially seem purely ethical, in a legal context, moral rights refer to specific legal safeguards. These rights include the "right of attribution," which allows an author to be acknowledged as the creator of a work, regardless of whether they still own the rights or have licensed it to someone else for publication or distribution. Moral rights also include the “right of integrity,” which provides the author protection against any modification, alteration, or distortion of their work that could be detrimental to their reputation.

Though uncertain, it’s possible that moral rights could apply to Generative AI systems. For example, if a Generative AI system uses someone's images as training data and generates works in that person's style, it has the potential to damage their reputation, particularly if the AI-generated works are of inferior quality or used in ways that the original artist disagrees with. Such a scenario could be seen as a violation of the artist's moral rights.

However, there are at least three challenges associated with applying moral rights to Generative AI:

It might be difficult to prove that an AI system has generated work in a specific artist's style without explicit knowledge that their work was used in AI model training and evidence that the specified output was influenced by that training.

Even if a violation is identified, enforcing an individual's moral rights against an AI system or its developers can be complex and challenging.

While moral rights are part of the Berne Convention, their implementation has been inconsistent. For example, the United States has not fully adopted moral rights,24 and therefore artists might have less protection against the use of their work by AI systems.

Potential solutions to address these challenges could involve establishing clearer laws and regulations regarding the use of training data, potentially requiring permission from artists before utilizing their works in this manner. Additionally, technological solutions could be explored to improve tracking and control over the use of an individual's work in AI systems, or even block the absorption of their style into AI models altogether (see the Glaze tool from The University of Chicago).

Finally, some organizations may choose to use AI systems or publish AI-generated works only if certain rights are respected. Here is an illustrative excerpt from “The Guardian's approach to Generative AI:”

With respect for those who create and own content

Many genAI models are opaque systems trained on material that is harvested without the knowledge or consent of its creators. Our investment in journalism generates revenues as we license that material for reuse around the world. A guiding principle for the tools and models we consider using will be the degree to which they have considered key issues such as permissioning, transparency and fair reward. Any use we make of genAI tools does not mean a waiver of any rights in our underlying content.

As Generative AI and other advanced technologies continue to develop and become more widespread, these questions will likely become increasingly important.

Policy options

Now that we have explored the current legal landscape, let's turn our attention to potential policy options for the future. Several proposals have emerged regarding how to treat AI-generated works:25

Keep AI-generated works in the public domain

Establish AI as an “electronic person”

Create specialized laws specifically for AI-generated works

Designate a human author for AI-generated works

These policy options are generally mutually exclusive although there could be overlap in some instances.

While the following sections present opinions from legal essays that offer compelling arguments for or against these policy options, there is limited data available on the broader preferences of legal experts or politicians regarding which option to adopt.

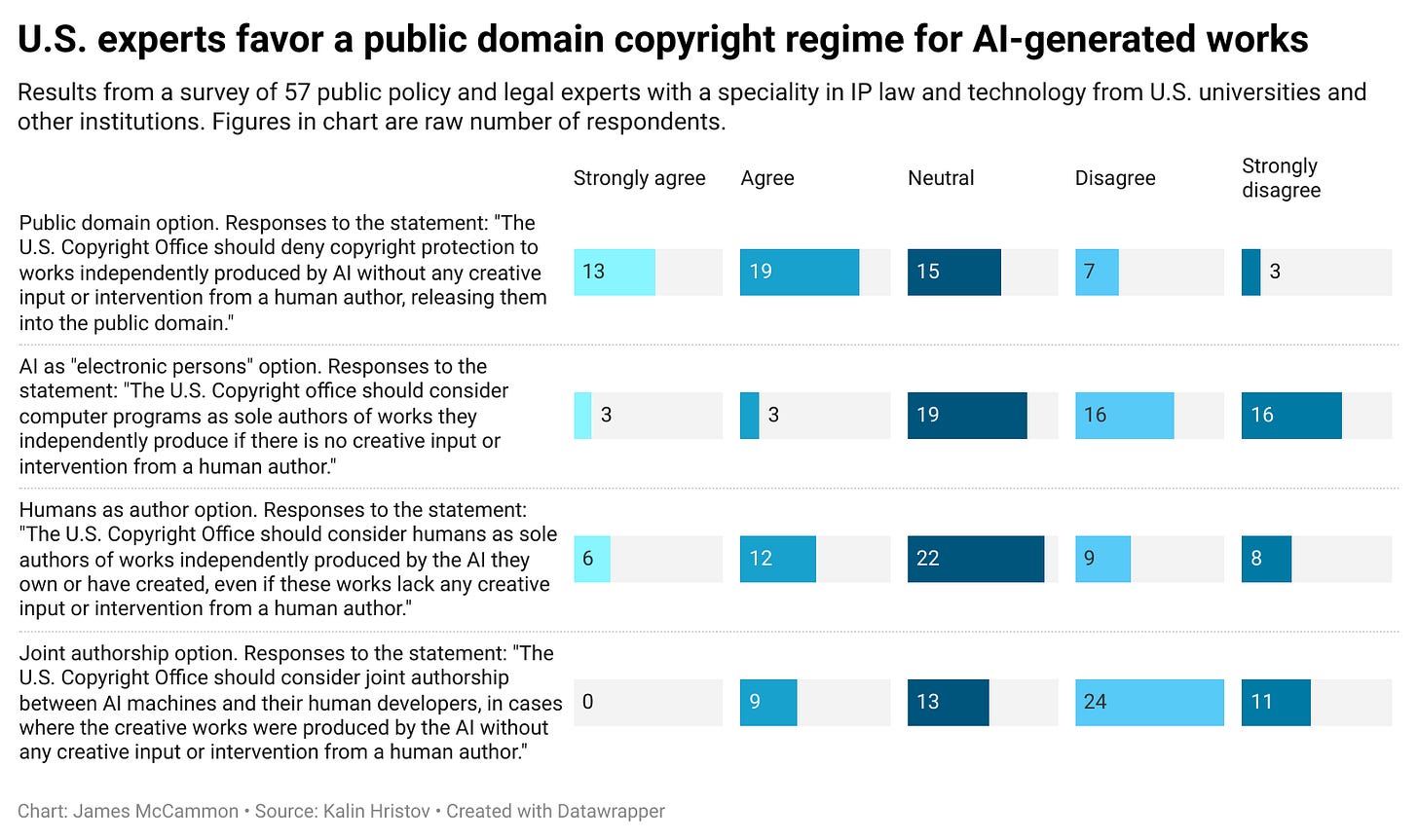

However, one small survey, conducted by teacher and researcher Kalin Hristov, is notable. The survey, likely conducted in 2017 (exact dates unknown), was sent to experts in IP law, public policy, and emerging technologies. Out of the 350 experts who received the 12-question survey, 57 responded. The survey results indicate that respondents generally do not support assigning AI sole authorship or joint AI-human authorship (just 6 experts and 9 experts, respectively, agreed or strongly agreed). However, there was a more favorable view towards assigning a human author to AI-generated works (18 experts agreed or strongly agreed). The most popular policy option among the respondents was to keep AI-generated works in the public domain (more than half of respondents, 32 experts, agreed or strongly agreed).

Option 1: Keep AI-generated works in the public domain

One potential approach to address copyright concerns surrounding AI-generated works is to designate them as part of the public domain (meaning anyone can freely use the AI output). As previously discussed, this approach is currently in wide practice globally including in the United States, Australia, and the EU. This option implicitly assumes that AI-generated work is authorless and therefore cannot qualify for copyright protection.

In the case of AI-assisted works, where humans and AI collaborate in the creative process, it would be necessary to distinguish and exclude the components generated by the AI. Only the human contributions that meet the criteria for independent copyright protection would be safeguarded, as exemplified in the Kashtanova case in the United States.

The implications of placing all AI-generated works in the public domain have raised concerns.26 The public domain option, although straightforward, exposes significant technological investments and efforts in AI — including output from platforms like Midjourney — to an unprotected legal landscape. This absence of protection may undermine the incentives for companies to advance Generative AI systems, potentially hindering their progress. Consequently, the availability of tools to support artists could be more limited. Moreover, authors themselves may be less inclined to create new works using AI if they do not have ownership rights over the output. The combination of these factors could lead to a potential decline in both the quantity and quality of artistic expression. Such an outcome would run counter to the very objectives that copyright was established to promote.

Furthermore, as Generative AI systems continue to advance at a rapid pace a public domain policy may create a greater temptation for authors to withhold information about the genesis of a work or falsely claim that a work primarily generated by AI was merely AI-assisted, in an attempt to secure copyright protection under false pretenses.27

Still, the recent surge in Generative AI innovation emerged amid a public domain copyright paradigm, highlighting that factors beyond copyright-centered market incentives also drive technological advancement and creative output. And concerns over false copyright claims is speculative at this point.

Carys Craig has argued that the public domain option is the most well-suited to protect creators and accord with the underlying tenants of copyright law:

[T]he protection of AI-generated works would not advance the kind of “creative progress” with which copyright is concerned—but worse, it could cause copyright to defeat its own ends, stultifying creative practices in a thicket of privately owned algorithmic productions.

Option 2: Establish AI as an “electronic person”

As previously mentioned, the European Union's Legal Affairs Committee (JURI) has proposed a potentially groundbreaking change: affording AI a special legal status akin to that of human beings. Under this proposition, an AI could be considered an “electronic person,” possessing rights that may be equivalent to, or perhaps more limited than, those of a human. Such rights could include authorial privileges within the realm of copyright law.

Regardless of one's personal opinions on this revolutionary proposal, it's important to note that this idea is unlikely to be implemented in the immediate future. Cornell Law School Professor James Grimmelmann provided a succinct summary of the situation in a 2016 essay:

It is possible that some future computer programs could qualify as authors. We could well have artificial intelligences that are responsive to incentives, unpredictable enough that we can't simply tell them what to do, and that have attributes of personality that make us willing to regard them as copyright owners. But if that day ever comes, it will be because we have already made a decision in other areas of life and law to treat them as persons, and copyright law will fall in line.

Option 3: Create specialized laws specifically for AI-generated works

Another possible approach is to create special-purpose, targeted laws specifically designed for AI-generated works (recalled these are termed sui generis rights). These laws would provide a regulatory framework without disrupting existing copyright laws centered around human authors.28 There are three main benefits to targeted laws for AI output:

Limited breadth of copyright protection: The scope of copyright protection for AI-generated works could be restricted. For instance, protection may only cover exact copies of AI-generated works, allowing greater flexibility for making derivative works based on AI output.

Shorter term of copyright protection: Copyright protection for AI-generated works could have a significantly shorter term than standard author's rights; for example a duration of three years. This time-limited protection recognizes the unique nature of AI-generated content and encourages ongoing innovation and creativity.

Country-by-country flexibility: Implementing special-purpose laws related to generative AI would allow different countries to establish varying copyright breadth and duration requirements that align with their respective economies and societies. However, given the current human-centered nature of the Berne Convention, updating it may be necessary for sui generis AI protections to be compliant.

By implementing these limitations, a dual-rights system could be established. This system would provide some level of protection to authors and companies utilizing Generative AI tools like Midjourney, while still prioritizing comprehensive protections for human-generated works. This approach ensures that human creativity remains incentivized and continues to receive the full range of copyright protections.

It's important to note that the creation of special-purpose laws for a specific industry may be seen as contradicting the principle of "technological neutrality," the idea that law should be independent of any specific technology and instead apply equally across technologies as they emerge.29 However, one might argue that Generative AI is a truly distinctive technology that must be treated uniquely.30

Adopting a sui generis approach also circumvents the challenging task of assigning a human author to AI-generated works under existing copyright laws. While this approach has its advantages, there are differing opinions on its feasibility.

James Grimmelmann again provides a counterargument against the implementation of sui generis rights, emphasizing the diverse nature of computer-generated works and the limitations of specific doctrines:

The problem of assigning copyright in computer-generated works may be a hard problem, but it is not a new problem. It is hard for the same reason that copyright has always been hard — it requires us to make objective legal judgments…Because computer-generated works are no different in kind than other works, special-purpose doctrines have little to offer...[T]he danger of claiming that there is "a" rule for computer-generated works is that it blinds us to the immense diversity that category encompasses.

That brings us to the final option: assigning a human author.

Option 4: Designate a human author for AI-generated works

If we presume that AI cannot be considered an author, one potential solution for addressing AI-generated content is to simply attribute authorship to a relevant human. Rather than introducing a sui generis system, this approach would utilize existing copyright standards and apply them to AI-generated works.

One suggested proposal is to expand the UK's "necessary arrangements" model more broadly. This model already attempts to assign a human author to AI-generated content by seeking to identify the party responsible for making the arrangements necessary to obtain the output. However, it is important to note that this proposal is not universally supported.31

Regardless of whether the "necessary arrangements" model is used or another legal framework is chosen, the primary challenge lies in identifying which human should be granted rights over AI-generated works. There are numerous possibilities:32

The Financial Backer: The entity providing the necessary financial resources to make the AI project possible.

The Platform Provider: The organization involved in setting up and operating the AI system itself.

The Model Subject. The person or group who served as the subject for a photo, illustration, or other creative work used in AI model training.

The Original Author. The person or group responsible for producing a photo, illustration, book, or other creative work used in AI model training.

The Data Collector: The party responsible for collecting and curating the data used in AI model training.

The Data Annotator: The individual or team that cleans, enhances, and labels the AI training data to improve its quality and relevance.

The Model Selector: The person involved in selecting the appropriate AI model for the project.

The Programmer: The individual responsible for training and fine-tuning the AI model.

The Model Deployer: The entity in charge of deploying and making the trained AI model available for use.

The User: The person or entity interacting with the AI platform and providing text input or instructions.

These roles can overlap or combine in different configurations.

The strength of each party's copyright claim on AI-generated works varies, but two particular personas are frequently discussed: The programmer and The User. Let's take a closer look at these two roles and their implications for copyright ownership of AI-generated works.

The programer as author

One approach to determining ownership is to consider the programmer's role. As highlighted by UCSC Computer Science professor Jason Eshraghian, there is an intuitive appeal to designating the programmer as the author of AI-generated content. Eshraghian explained in a Nature Machine Intelligence article that since programmers typically exhibit skill and creativity in developing the code that trains the AI model, they could be said to have a claim of authorship on the resulting AI-generated works.

A prominent UK case, Nova Productions Ltd v Mazooma Games Ltd., ruled in favor of the programmer, applying the “necessary arrangements” doctrine mentioned earlier. The court concluded that Mr. Jones, the programmer of an electronic pool game, was responsible for the necessary arrangements and thus held the copyright for the computer-generated images displayed to users during gameplay.

However, applying the programmer-as-author model as a global copyright framework faces several critiques:33

Many other parties involved in the creation and training of an AI system may also be said to exercise a degree of skill or creativity. Why should the programmer’s contribution be prioritized over theirs?

The programmer (or their employer) already possesses the copyright for the software used to train and optimize the AI model, which can be monetized through sales or licensing. This offers ample incentive to innovate without needing to further grant them copyright over the AI-generated content.

Granting ownership to the programmer could potentially discourage users from utilizing the AI system to generate new creative works. If artists cannot reap the benefits of selling or exhibiting works they generate using the AI system, they may have little incentive to use it. This undermines the very purpose of copyright, to incentivize the creation of new works.

The programmer may lack comprehensive knowledge or control over the specific outputs generated by the AI model. This might hinder their ability to enforce their copyright protection.

The expertise of the programmer may not align with the intended usage of the AI model. While a programmer may excel at developing a sophisticated text-to-image platform through advanced model training, it does not necessarily mean they are the party most skilled or likely to benefit from the usage of the AI platform.

The user as author

As has been discussed at length in this article, under current copyright laws, the user of a platform that produces AI-generated output is explicitly not considered the legal author due to their perceived minimal and nonexpressive contribution. However, there are strong arguments from legal scholars as to why the user is actually the most appropriate party to assign copyrights to:34

Traditionally, copyright law has recognized the person who “fixes” a work in a tangible medium as the author. For example in Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, discussed at the beginning of this article, Napoleon Sarony was granted copyright for a photograph he took of Oscar Wilde. Although Oscar Wilde was the subject, Sarony was considered the author because he “fixed” the photograph. Similarly, the user of an AI program directly causes the AI-generated work to materialize and therefore become “fixed.” The user therefore has a claim to ownership based on their instructions.

Granting copyright to the user aligns closely with the philosophical purpose of copyright law, which is the advancement of society through creative and scientific output. By granting copyright to the user — the party that brings the work into existence and “fixes” it — they are incentivized to continue producing more works, fulfilling the core objectives of copyright law.

In some jurisdictions, there is legal precedent for granting copyright protection to minimally expressive acts. For example, in the United States, someone who records a live performance of improvised jazz is considered the “author” of the sound recording,35 even if their creative input is as simple as pressing the “record” button. Extending copyright to users of generative AI tools would follow this precedent, even if their contribution is as basic as clicking a “Generate” button or providing a simple prompt.

The user often pays for the rights to use the programmer's AI platform, either through purchase, lease, or license, which supports their claim to ownership.

Legal scholar Robert Denicola further argues that designating the user as the owner simplifies the distinction between AI-assisted and AI-generated works, aligning with the principle that a user who employs a computer as a tool in their own expression should own the resulting work. As we have previously discussed, distinguishing between these two categories becomes increasingly challenging in the rapidly evolving landscape of AI technology.

If AI-generated works are owned by entities other than the user or are deemed ineligible for copyright protection altogether, we would remain entangled in the ongoing debate between AI-assisted and AI-generated works, which Denicola deems “an obviously difficult, indeed indeterminate, and ultimately pointless endeavor.”

The European Union has also considered the user as the potential owner of AI-generated content in their “Report on intellectual property rights for the development of artificial intelligence technologies,” suggesting that copyright should be granted to the individual who lawfully prepares and publishes the creative work, provided that the designers of the underlying technology do not oppose such use.

At a time when artistic creation by AI is becoming more common…it is proposed that an assessment should be undertaken of the advisability of granting copyright to such a ‘creative work’ to the natural person who prepares and publishes it lawfully, provided that the designer(s) of the underlying technology has/have not opposed such use.

Assigning the user as the author of AI-generated works presents its own set of challenges, particularly when it comes to global implementation. Unlike the existing approach of placing works in the public domain or establishing specialized sui generis protections, creating a worldwide copyright system with more lenient protections for users would require international harmonization and may not receive universal support. It would involve either drafting a new international treaty or amending the Berne Convention. While there are instances where copyright protection has been granted for works with minimal creative input, designating users as authors of AI-generated works could unintentionally extend copyright to "merely mechanical" creations, potentially affecting other aspects of copyright law. Therefore, if such an option were pursued, it would need to be carefully crafted to minimize unintended consequences and gain support from advocates who prioritize human-centered approaches.

Special shoutouts

“Research Handbook on Intellectual Property and Artificial Intelligence” edited by the prodigious Ryan Abbott.

The time traveler Pamela Samuelson who somehow back in 1986(!) wrote “The Future of Software Protection: Allocating Ownership Rights in Computer-Generated Works,” which is arguably still the single best legal treatment of how copyright should treat AI-generated works.

This concludes my wonderful little article on copyright law and AI-generated content. I hope you had fun reading it! What’s your preferred policy option? What other questions do you have about Generative AI and copyright law? Do leave a comment below and make sure to smash the subscribe button.

What a sick burn!

For a deeper discussion of the four theoretical justifications for copyright law — fairness theory, personality theory, welfare theory, and cultural theory — see Giancarlo Frosio’s “Four theories in search of an A(I)uthor” available for free here, but also featured in the “Research Handbook on Intellectual Property and Artificial Intelligence.”

The first even copyright regulation enacted was The Statute of Anne, passed in 1710 by Parliament of Great Britain; it stated the importance of copyright was, “[F]or the Encouragement of Learned Men to Compose and Write useful Books.” Copyright protection is also enshrined in the U.S. Constitution (art. 1, § 8, cl. 8) in order “To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”

Creative works that fall outside of copyright law include utilitarian designs and functional objects. This traces back to the idea-expression dichotomy and the threshold of originality. For more, see this short description from the U.S. Copyright Office or this case from the EU.

For example, In the United States see 17 U.S.C. § 106. The Berne Convention lists similar exclusive rights as the United States, but at a slightly more granular level. For instance, calling out “performance” and “recitation” as two distinct rights.

For example in cases involving the legal status of the data used for model training.

This is the term under Berne for most works. In the United States the term is generally the life of the author plus 70 years.

See, for example, Enrico Bonadio and Luke McDonagh’s article, “Artificial Intelligence as Producer and Consumer of Copyright Works: Evaluating the Consequences of Algorithmic Creativity” in which the authors note that, “A sui generis right protecting AI-created works might fit well into the ‘related right’ category of rights that aims at incentivising investments in crucially relevant technological fields.” The authors reference Directive 2001/29/EC, which notes that, “Technological development has multiplied and diversified the vectors for creation, production and exploitation. While no new concepts for the protection of intellectual property are needed, the current law on copyright and related rights should be adapted and supplemented to respond adequately to economic realities such as new forms of exploitation.”

In fact, Atari had to appeal to the district court twice before finally being granted their copyright.

See the Atari Games Corp. v. Oman Wikipedia article for an accessible discussion: “The decision builds on early copyright cases that treat video games as an audiovisual work, including Atari v. Amusement World (1981), Atari v. North American Phillips (1982), Stern Electronics, Inc. v. Kaufman (1982), and Midway v. Artic (1983). The series of decisions became influential on the copyrightability of software more generally.”

Here are the definitions GPT-4 provided when I asked:

“AI-generated images refer to images that are created entirely by artificial intelligence systems, with minimal or no direct human intervention. These images are generated through the sophisticated algorithms and neural networks of AI models, which can learn from vast amounts of data and produce novel visual content that resembles real-world images. AI-generated images are primarily the product of machine intelligence, where the AI system generates every aspect of the image, including its content, style, and composition.

On the other hand, AI-assisted images are those that involve the collaboration between artificial intelligence systems and human creators. In this context, AI technologies serve as tools or aids to enhance and augment human creativity and productivity. The AI system assists in various stages of the image creation process, such as generating suggestions, providing automated editing features, or offering real-time feedback. However, the final outcome and creative decisions are ultimately made by human users, who actively contribute their artistic vision and subjective judgment.”

See “The Vanishing Author in Computer-Generated Works: A Critical Analysis of Recent Australian Case Law” By Jani McCutcheon.

See “People Not Machines: Authorship and What It Means in the Berne Convention” by Jane C. Ginsburg.

The chess-playing supercomputer Deep Blue was considered a huge advance in AI; now we have Mittens the chess playing cat. Or consider spell checking, “Though common to the point that people take them for granted today, spell checkers were considered exciting research under the branch of artificial intelligence back in 1957.” When I was a child talking computers very much would’ve been considered AI; now they are simply “intelligent assistants.” Ho hum.

See also “People Not Machines: Authorship and What It Means in the Berne Convention” by Jane C. Ginsburg.

This description is simplified. First, the Berne Convention only includes authors’ rights, related rights are included in the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Rome Convention. Second, most digital works are actually covered under the WIPO Copyright Treaty (WCT), which is a special agreement under the Berne Convention, but technically not a part of the core of Berne (meaning there are some parties to the WCT that are not signatories of the Berne Convention in full). Third, for all intents and purposes Berne — as well as other major copyright agreements and conventions — are actually implemented via the WTO’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), which incorporates copyright standards into the WTO’s enforcement and dispute settlement process. Fourth, there has been some questioning about whether, in practice, EU law actually defers to TRIPS. For example, see this 2010 article in the European Journal of International Law about whether the decision in Microsoft v. Commission was TRIPS compliant.