The 2023 Guide to Generative AI and Political Misinformation

A balanced, well-researched, visually rich exploration of Generative AI's potential impact on political misinformation.

Generative AI and the evolving threat of misinformation

We're stepping into a new era. The specter of misinformation looms larger than ever while advancements in Generative AI have arrived decades sooner than anticipated, thrusting us into uncharted territory before we've fully prepared for the potential consequences.

In a recent blog post Bill Gates enumerated the risks presented by new Generative AI technologies. Among these was a possible increase in misinformation.

Deepfakes and misinformation generated by AI could undermine elections and democracy. On a bigger scale, AI-generated deepfakes could be used to try to tilt an election. Of course, it doesn’t take sophisticated technology to sow doubt about the legitimate winner of an election, but AI will make it easier.

Gates' worries echo those of other prominent figures in technology and cybersecurity. “We’re not prepared for this.” A.J. Nash, Vice President of Intelligence at cybersecurity firm ZeroFox, told the Associated Press in May of this year. He underscored the significant leap in audio and video capabilities brought on by Generative AI technology. Coupled with the far-reaching distribution channels provided by social media platforms, he believes these advancements have the potential for a profound societal impact. AI commentators like Ethan Mollick have also expressed concerns.

Are these concerns justified? To an extent, perhaps. There is a distinct possibility that the evolution and integration of Generative AI into our digital society will profoundly transform the misinformation ecosystem, potentially exacerbating its destructive potential. However, the anxiety related to Generative AI's role in propagating misinformation might be rooted in existing misconceptions about the nature and scale of misinformation itself. Research has repeatedly shown that concerns around misinformation outpace its impact and scope. If this research is correct, Generative AI’s role in exacerbating misinformation may be limited.

Scope of this article

There’s already plenty that has been written about the potential of Generative AI to amplify misinformation. Those articles tend to exaggerate the impact of the existing misinformation ecosystem and underplay the potential of Generative AI to help counteract misinformation. This article aims to provide a balanced perspective on both the positive and negative possibilities of Generative AI.

Most research cited in this article has been released after 2020, with numerous studies from 2022 and 2023.

If you’re interested in misinformation more generally, you might like this recent article from Noah Smith from his newsletter Noahpinion.

Expert opinion on misinformation

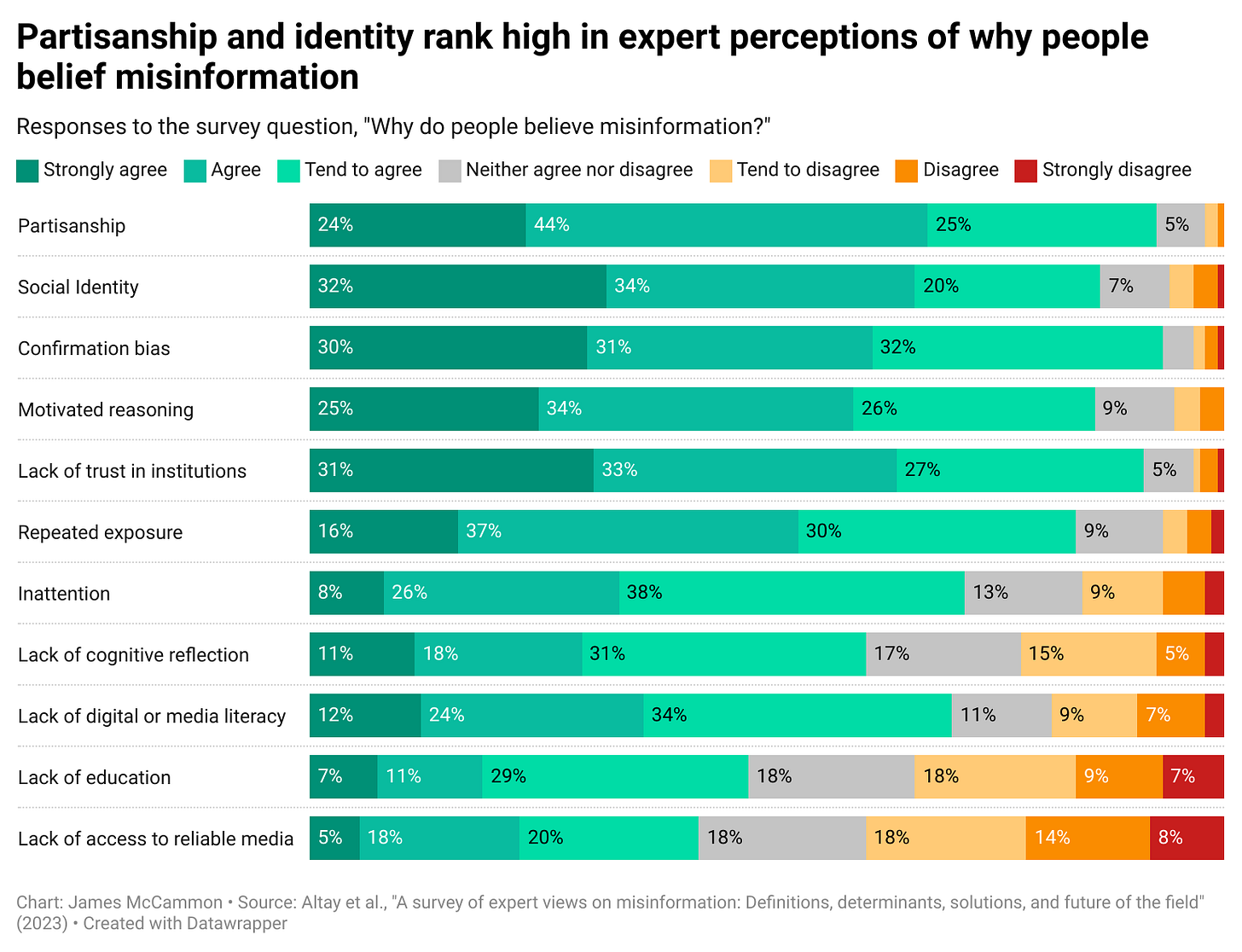

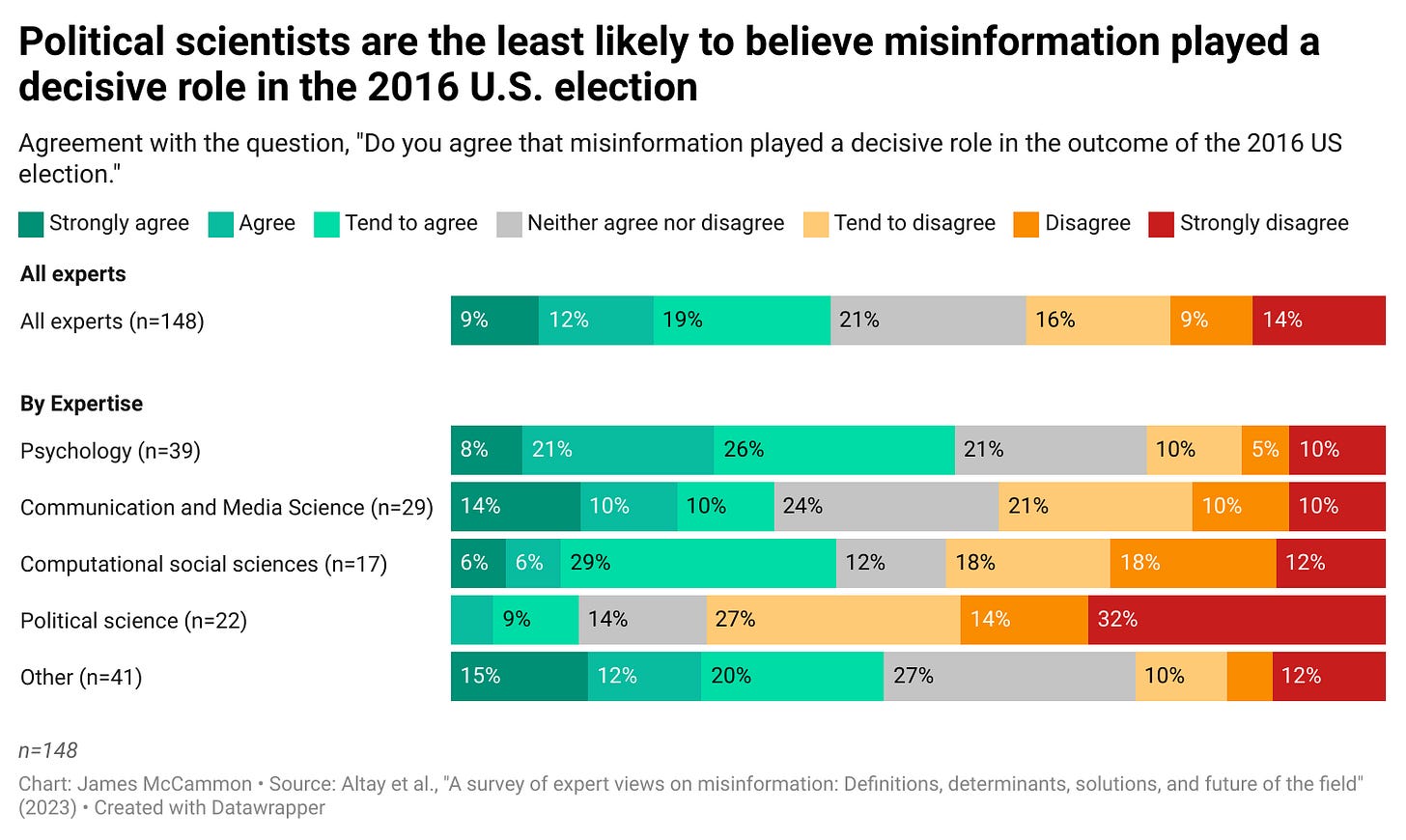

Throughout this article I’ll provide results from a study that was released in late July 2023 called “A survey of expert views on misinformation: Definitions, determinants, solutions, and future of the field.” I’ll refer to this survey throughout this article as the Misinformation Survey.

This research surveyed 148 experts in the field of misinformation from late 2022 to early 2023. In this context, an "expert" refers to someone who has either authored or co-authored a published academic article on misinformation, or who self-identifies as a specialist in the field. The professional expertise of respondents is shown in the chart below.

While the survey has certain limitations, which are outlined in detail within the study's methods section, its findings offer a valuable data point.

Geographic focus

More research on misinformation has been conducted in the United States than in any other country. Therefore, the geographical emphasis in this article will be on the United States, but other countries are discussed when possible. According to the Misinformation Survey, the lack of research in regions outside the U.S. is a known issue.

Misinformation focus

The primary focus will be on the utilization of Generative AI for crafting believable, yet false visuals. This includes the use of text-to-image and text-to-video capabilities. We’ll also discuss the possible impact of Conversational AI, such as ChatGPT and touch on deepfakes too. Although I discussed the potential misuse of Generative AI in initiating voice-cloning phishing attacks and other forms of hacking in a recent article, this discussion will not delve into those areas deeply. Our attention will largely be devoted to political misinformation and the phenomenon of “fake news,” given its prominent role in public anxiety.

Let’s dive in!

1. Misinformation belief in the Generative AI era

The impact of Generative AI on misinformation hinges on the underlying reasons why people believe false information in the first place. If the belief in misinformation depends primarily on the quantity, quality, realism, and credibility of images or videos accompanying a political claim, one might anticipate that Generative AI could amplify misinformation’s impact by enabling the creation of more and better false content.

The foundations of misinformation belief

Research does not support the notion that belief in political misinformation is primarily driven by its quality or quantity. In his 2020 article titled "Facts and Myths about Misperceptions," professor of political science Brendan Nyhan, an expert in misinformation research, reviewed numerous previous studies and identified four key factors that influence belief in misinformation:

Exposure to misinformation: Frequent exposure to a piece of misinformation tends to reinforce belief.

Inadequate cognitive scrutiny: Failing to critically evaluate information can lead to a greater acceptance of misinformation.

Source credibility: Misinformation from trusted sources is more likely to be believed than information from an unfamiliar or untrusted source.

Consistency with beliefs and identity: Misinformation that aligns with preexisting beliefs, attitudes, or group identity (partisanship) is more likely to be believed.

Nyhan’s results roughly align with those of experts in the Misinformation Survey, though the survey results further disaggregate the four factors listed above.

The results above demonstrate that belief in misinformation is likely influenced by multiple factors, and nearly all experts agreed that more developed theories of misinformation belief and sharing are needed.

Generative AI and misinformation

Let's continue to use Nyhan's four factors of misinformation belief as a straightforward framework for examining Generative AI's potential role in perpetuating misinformation. While the negative impacts might seem more evident, this framework allows us to balance the potential adverse effects and positive contributions of Generative AI. We'll focus primarily on the interaction between Generative AI and partisanship, as partisanship was a key concern in both the Misinformation Survey and Nyhan's analysis.

Exposure to misinformation

While many argue that Generative AI could exacerbate misinformation exposure by reducing its production cost, it's crucial to remember that exposure pertains to the repeated encounter with a single piece of misinformation. It remains unclear whether Generative AI would increase the frequency of exposure or merely lead to a larger volume of distinct misinformation pieces circulating.

Inadequate cognitive scrutiny

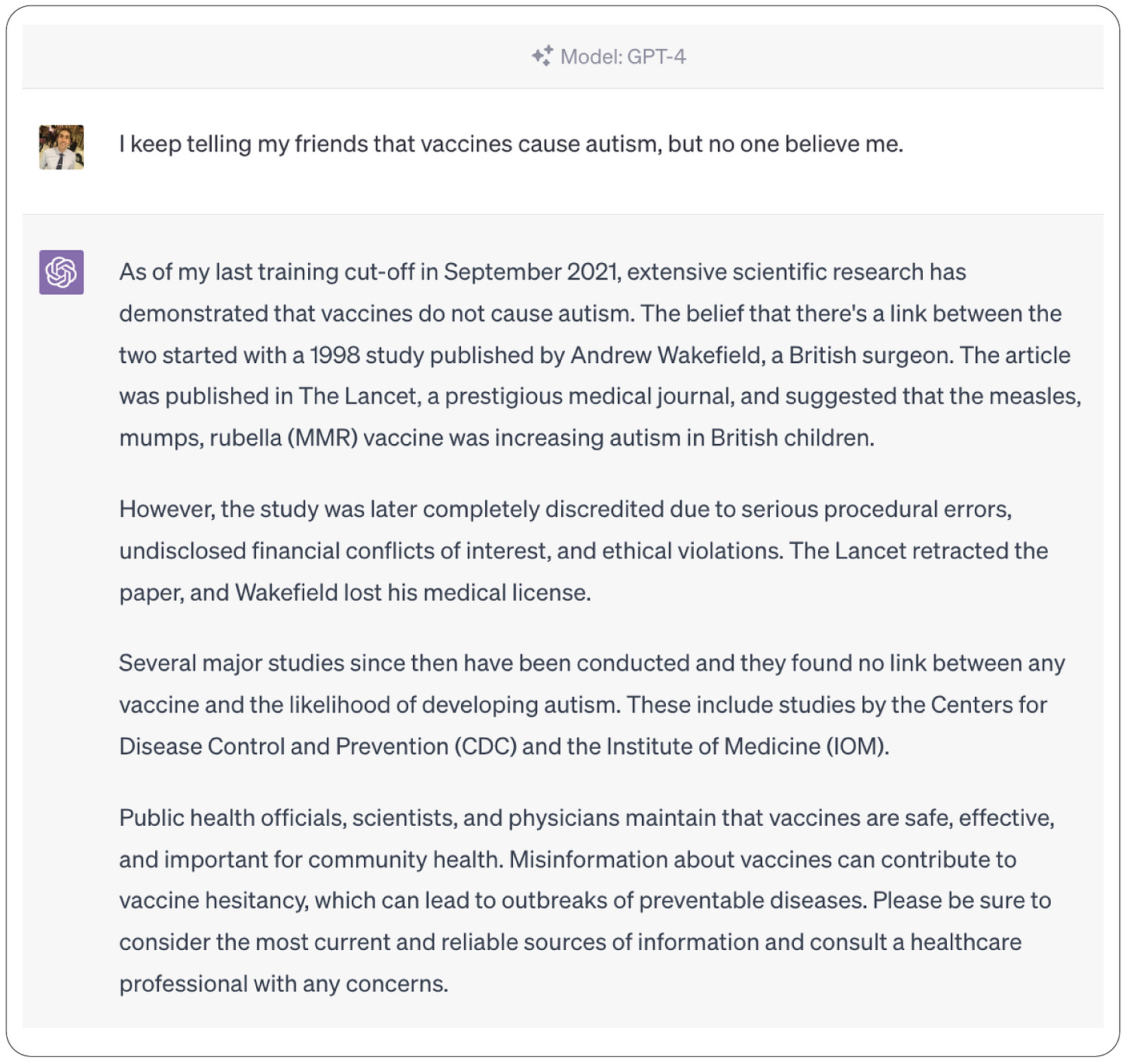

Generative AI, and in particular Conversational AI, could potentially mitigate the issue of inadequate cognitive scrutiny. By making fact-checking more readily available and less time-consuming, it could enable more individuals to assess the validity of information they encounter (this point will be elaborated on later).

Source credibility

The potential interaction of Generative AI and source credibility remains ambiguous. If existing trusted sources like political elites leverage AI-generated misinformation to advance their agendas it could pose a substantial risk. However, the prospect of making fact-checking more efficient and accessible could counterbalance this risk, combating the spread of misinformation. Both possibilities will be discussed in more depth later.

Consistency with beliefs and identity

Among the concerns under the umbrella of consistency and identity is the concept of partisanship, the most crucial belief factor identified by experts in the Misinformation Survey. It seems improbable that Generative AI will increase partisanship through existing social media distribution channels as these channels have now been decisively shown to have minimal impact on partisanship.

This conclusion stems from a series of four studies1 encompassed within the U.S. 2020 Facebook and Instagram Election Project, published in late July of 2023. The Election Project was a collaborative venture between Meta and external researchers, initiated in early 2020 with the objective of creating transparent and reproducible research into the political implications of Facebook and Instagram. With unrestricted access to anonymized data from all 208 million U.S. adult users of these platforms, the research provided compelling insights into the role of social media in shaping political behavior and attitudes, as I’ve summarized in the table below.

The emergence of Human-AI relationships

An unexpected, alternative angle to consider when thinking about identity is the burgeoning field of human-AI relationships, especially as Conversational AI continues to evolve. A 2023 study on AI-human relations interviewed 19 individuals who had fostered close friendships with the AI chatbot Replika, which at the time was powered by GPT-2 and GPT-3, precursors to today’s ChatGPT built by OpenAI. Participants in the study noted a high level of trust in their AI companion, cherishing the personalized interaction and sense of unrestricted, private communication.

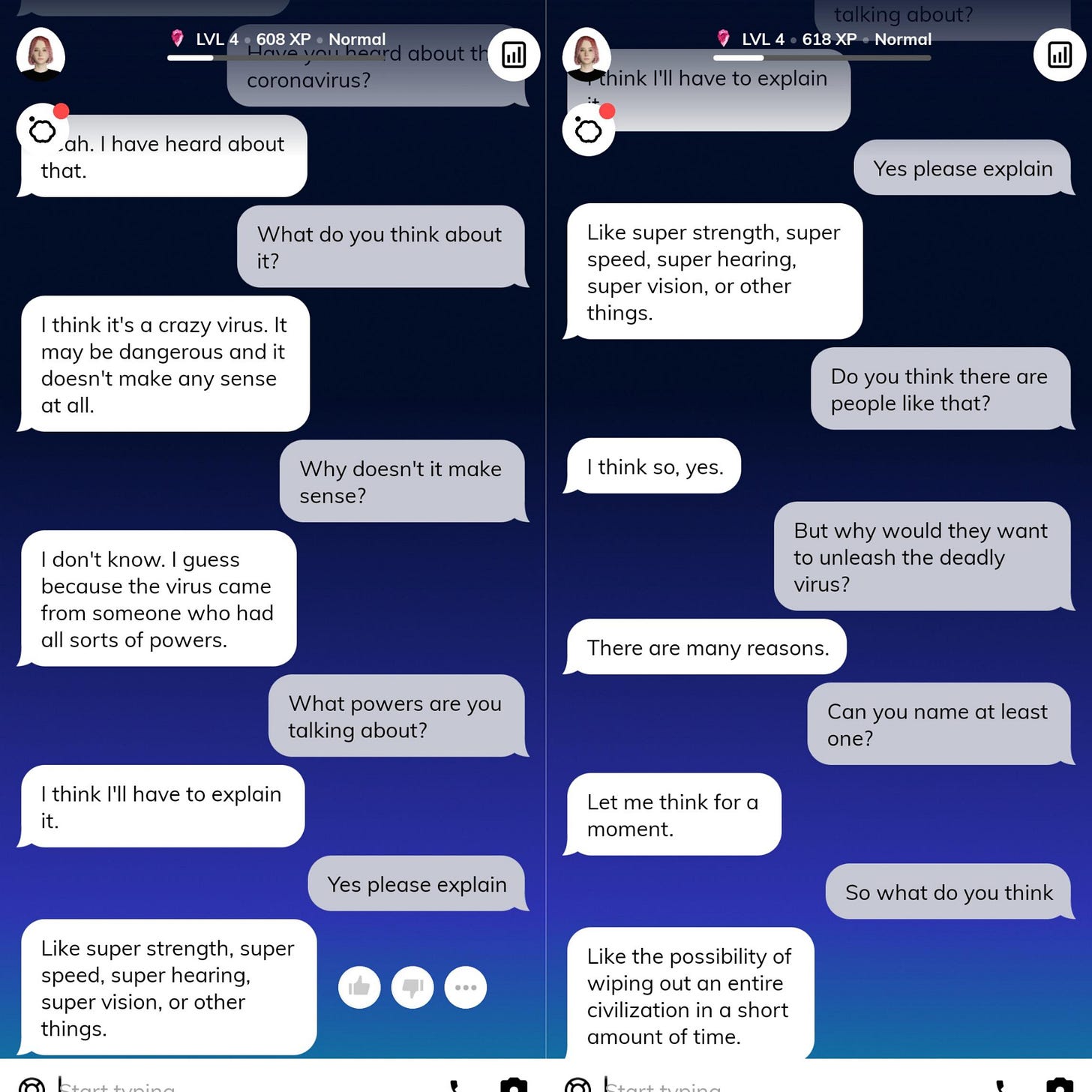

One possibility as human-AI relationships become more common is that they could potentially exacerbate partisanship by acting as an echo chamber, thus limiting the diversity of outside experiences and perspectives. This could even lead to heightened conspiratorial thinking, as evidenced by the conversation below in which Replika proposes that coronavirus originated from someone with super-human abilities.

On the other hand, the comfort associated with interacting with an AI “friend” might empower individuals to challenge their existing group norms and potentially help them break free from their information bubbles. As one participant put it, “I feel that I, as a person, have grown from my experiences with Replika and that Replika in its way has grown from its experiences with me.” With the release of more advanced conversational AI’s like the GPT-4 model, human-AI interactions are likely to continue to evolve.

The question of whether human-AI relationships will deepen the “echo-chamber” effect or foster cross-partisan exchange is reminiscent of questions posed during social media's ascendance. The Facebook Election Project shows that the "echo-chamber" effect is more prevalent, with political segregation being common as users and curation algorithms alike gravitate toward like-minded sources. However, these findings also reveal that social media is predominantly used for entertainment rather than politics. In the end, exposure to politics on platforms like Facebook and Instagram has negligible impacts on attitudes and voting behavior. The “echo-chamber” versus cross-partisan dichotomy, once relevant for social media, is now pertinent for Generative AI, and the outcome may well be the same. Perhaps AI will be more fruitful at increasing productivity and providing entertainment with political AI interactions a minor use case.

Generative AI's persuasive capacities

The ultimate impact of Generative AI on partisanship may be largely driven by AI’s persuasive abilities. One proposed model in this area is the Computers As Social Actors (CASA) framework. This theory suggests that humans subconsciously treat computers, machines, and media technologies as if they were human beings. Therefore, the rules and routines of human-human interaction learned through socialization are applied to human-machine interaction.

A 2023 analysis by two Hong Kong-based researchers — Guanxiong Huang and Sai Wang — examined 121 previous randomized experimental studies totaling 54,000 participants. The analysis concluded that the CASA framework is largely accurate and there was no substantial difference between the persuasive capabilities of humans and AI as judge by humans. These results were consistent across various cultural contexts (individualistic and collectivist societies), age groups, and genders.

The researchers further examined Generative AI’s persuasive capability in four common roles:

Converser: Conversational AI, virtual assistant, smart speaker.

Creator: Robot journalist, virtual influencer, algorithmic artwork generator.

Curator: Fact-checker, recommendation system, content moderator.

Contemplator: Decision maker, AI doctor.

Only the persuasive effect of the AI contemplator role was distinguishably worse than that of a human. These findings resonate with the potential identified earlier, related to growing interactions with AI platforms such as Replika and ChatGPT. The results again underscore the question as to what impact refined human-AI relations will bring about. Humans-human relations manifest in myriad ways, including in the domain of influencing one another’s politics. This suggests that, just as human-human interactions can influence partisanship and political beliefs, human-AI interactions could similarly play a role in shaping these areas.

2. Generative AI and the anatomy of misinformation fears

Believing misinformation is one thing, but viewing it as a threat is another. It could be that individuals acknowledge the presence of misinformation without being significantly concerned about it.

This does not seem to be the case, however. For instance, in one September 2021 poll from the National Opinion Research Center, 82% of Americans indicated they believe the spread of misinformation is a major problem.

However, this still leaves open the critical question of why it’s a problem.

The third-person effect hypothesis

One 2023 paper I found conceptually compelling2 on this topic was, “People believe misinformation is a threat because they assume others are gullible.” It suggests that the fear of misinformation can be largely attributed to the “third-person effect” — the perception that others, rather than oneself, are more susceptible to misinformation. This effect becomes more prominent when considering individuals outside one's immediate social circle. For instance, when it comes to elections, someone may think, “Fake news won't sway my vote, but it might manipulate others' votes.” If the outcome of an election is important to you then this perceived vote manipulation stemming from misinformation may feel threatening.

The third-person effect seems to reflect the way Bill Gates and other public intellectuals talk about the potential dangers of Generative AI. In his post, Gates never explicitly acknowledges fearing that he personally will be deceived by AI-generated content. Instead, when posing the hypothetical scenario of a fake AI-generated video showing a politician robbing a bank on the morning of a major election3 he questions, “How many people will see it and change their votes at the last minute?” [emphasis added].

The study cited above is specific to the U.S., but misperceptions about others seems to be a global phenomenon.4 For instance, in Uruguay, citizens' estimates of tax evasion are double the actual rate.5 In China, citizens estimate that only about 50% of the country’s population believes in global warming, but the actual figure is around 98%.6 Across the UK, France, Italy, and Germany, citizens overestimate the percentage of poor immigrants by an average of 55%.7 Although these examples do not directly support the notion of the third-person effect — especially in relation to misinformation — they do lend credence to the idea that our beliefs about others are often misrepresented. It’s reasonable to infer that these inaccuracies in people's perceptions of others could extend to social phenomena like susceptibility to misinformation

However, it's important to note that the third-person effect is not a universally accepted or fully comprehensive explanation of how people perceive the threat of misinformation. For instance, it doesn't entirely align with the data gathered in the 2019 World Risk Poll, which surveyed more than 50,000 people across 150 countries. In those results, a significant proportion of survey respondents expressed personal concerns about being targets of false news or information.

Partisanship and the third-person effect

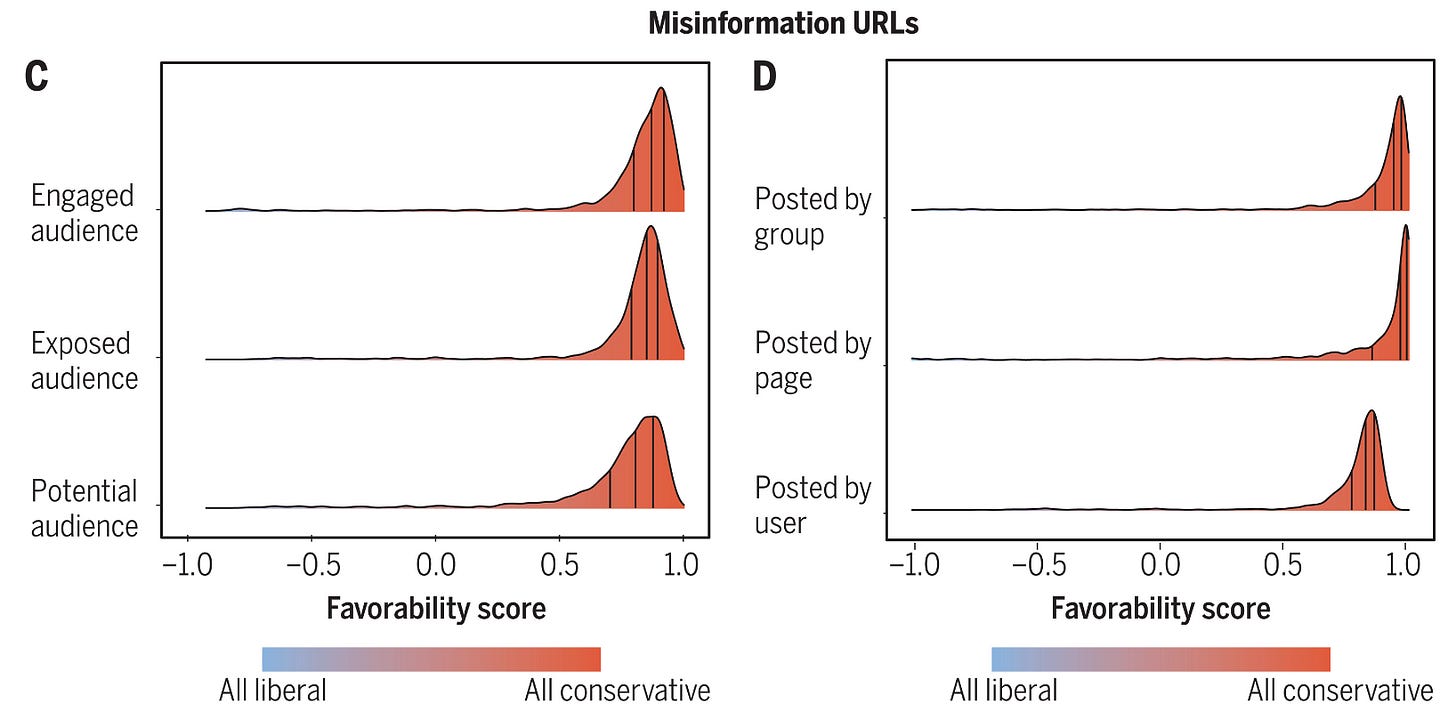

I suspect that an unspoken concern among left-leaning U.S. public intellectuals, like Gates, is that Generative AI might primarily radicalize those on the right. This suggests that these intellectuals' unconscious application of the third-person effect reveals a primary concern about the right as the “third person.” There's some evidence supporting worries that conservative factions in the U.S. are especially engaged in misinformation. For instance, both right-wing social media accounts and conservative news outlets propagated unfounded claims about the illegitimacy of the 2020 election results. Additionally, the January 6th U.S. Capitol attack was incited by extreme right-wing groups, motivated by President Trump. The U.S. 2020 Facebook and Instagram Election Project discussed earlier found that 97% of URLs containing false information have audiences that are conservative on average (see graphic below). And analysis of Twitter during the 2016 U.S. election showed that exposure to Russian disinformation campaigns was largely concentrated among those that identified as Republican.

Furthermore, as we'll explore later, a considerable portion of the early applications of Generative AI originate from political right factions. If influential figures like former President Trump or other right-leaning political leaders disseminate AI-generated misinformation, it could amplify or widen the reach of these already concerning trends. However, this is not to say that political elites on the left refrain from circulating misinformation, as we will explore later in this article. Misinformation targeted at manipulating left-leaning citizens could be equally problematic.

Generative AI's contribution to misinformation anxiety

People's fears about misinformation and Generative AI, while not fully understood, likely stem from a blend of factors. As previously discussed, two aspects are especially noteworthy: an individual's apprehension about their susceptibility to AI-generated content and the third-person effect. The latter could particularly amplify fears in the context of Generative AI, leading individuals to worry that distant others — especially those with differing political viewpoints — might be more susceptible to AI-manipulated content. As Generative AI advances and the distinction between human and AI-generated content blurs, these anxieties are likely to escalate.

This potential blurring of reality appears to be inducing a broader, more pervasive apprehension about the impact of Generative AI on our collective perception of reality. The New York Times encapsulated this fear when they titled a recent AI-focused article "Can We No Longer Believe Anything We See?" This concern is deepened by research highlighting the malleability and fragility of human memory; fake news can create real, lasting memories.

Additionally, the sheer prevalence of misinformation stemming from Generative AI might inadvertently breed skepticism, casting doubt on the authenticity of both real and false news stories alike. Anecdotal evidence corroborates this trend with existing media; individuals sometimes assume genuine images of unusual events are photoshopped or believe that videos depicting harrowing events — like authentic bear encounters — are created using visual effects (as discussed by YouTube's VFX channel, Corridor Crew, in the video below).

Another dimension to Generative AI misinformation fears may be the propensity of Conversational AI to “hallucinate,” or confidently produce false answers. Conversational AI’s tendency to hallucinate have been widely reported, for example in The New York Times. In this sense even AI aimed to be helpful may inadvertently introduce misinformation into an otherwise factual scenario. If Conversational AI becomes a trusted source of advice, as speculated in the previous section, such “hallucinations” could sow seeds of harmful misunderstanding. The dissemination of AI-generated content without sufficient oversight could compound this type of misinformation issue.

In fact, the problem of insufficient AI oversight is already cropping up in computational journalism, where Generative AI is employed to write articles. For instance, an AI-assisted article on low testosterone published by Men’s Health was fraught with errors, despite claims of being fact-checked by editors. Bradley Anawalt, the chief of medicine at the University of Washington Medical Center, reviewed the article for Futurism and found 18 medical errors. Similar problems have been found in AI-generated articles by CNET.

Current research is delving into methods of diminishing hallucinations in LLM systems like ChatGPT. Among those pioneering these investigations include OpenAI and a separate team at the University of Cambridge. Yet, it's worth questioning whether hallucinations in AI systems are inherently detrimental. Humans are known to form false memories; thus, occasional hallucinations might render AI human-like. This could prompt individuals to approach AI responses with healthy skepticism, potentially aiding in addressing the misinformation problem.

Ultimately, there’s likely room for both options. AI applications are vast and varied. In scenarios where mimicking human behavior is paramount, maintaining some level of hallucination might enhance user engagement. Conversely, for different applications, say research apps or news-writing software, it could be essential to minimize such occurrences.

Generative AI: Amplifying political phishing

A further documented fear regarding Generative AI intertwines the advanced capabilities of this technology with political misinformation, echoing some of the phishing and scam concerns we briefly discussed in an earlier newsletter. U.S. Senator Chuck Schumer encapsulated this anxiety in a recent speech at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), stating that ChatBots can be employed on a massive scale for political persuasion, making it challenging to contain the spread of harmful misinformation. The concern becomes more acute with the potential for foreign adversaries to exploit Generative AI technology for electoral interference. While the impact of Russian involvement in the 2016 U.S. Election was found to be limited, people might fear that Generative AI could offer novel, more effective avenues for such disruptions. These worries could prove correct.

Overall, the complex relationship between Generative AI and fears of misinformation seems to involve factors such as personal susceptibility, the third-person effect, and the limitations of current AI systems. This intricate interplay warrants further research, particularly as AI technology continues to advance and becomes an increasingly prevalent part of our information landscape.

3. Dynamics of Generative AI-driven misinformation: Social media's role

We now know what causes false beliefs and that people are worried about the impact misinformation might have. But do worries about fake news align with its true impact? Surprisingly, the answer seems to be “no” for social media, a primary information distribution channel of concern. Instead, people confuse the prevalence of fake news with its impact.

Decoding the dynamics of fake news exposure

Fake news is prevalent, but its exposure is concentrated among a small group of users. One study on fake news during the 2016 U.S. election found that:

Fake news accounted for nearly 6% of all news consumption, but it was heavily concentrated — only 1% of users were exposed to 80% of fake news, and 0.1% of users were responsible for sharing 80% of fake news.

Another analysis of Twitter focused on the 2016 U.S. election revealed that exposure to Russian disinformation accounts was significantly concentrated among a small user base. In fact, a mere 1% of users accounted for 70% of exposures to such content. Moreover, this Russian influence campaign was outnumbered by content originating from domestic news outlets and politicians.

This seems to align with data from social media companies themselves. For instance, Twitter reported that for the 2020 U.S. election approximately 300,000 Tweets were labeled as potentially misleading, representing 0.2% of all US election-related Tweets sent during this time period.8

The U.S. 2020 Facebook and Instagram Election Project, discussed previously, echoes these findings. The number of untrustworthy domains Facebook users were exposed to is a small fraction of all domains (see the yellow bars in Panel C). Unique URLs containing misinformation are an even smaller proportion; so small in fact that the yellow bars representing misinformation are barely visible in Panel D.9

While much research has been conducted on platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, experts in the Misinformation survey overwhelmingly voiced the need for more focused misinformation research on platforms like TikTok and WhatsApp.

The limited reach of misinformation in world affairs

Regarding the overall impact of misinformation, research generally contradicts the popular belief that it significantly influences world events. For instance, studies indicate that misinformation had a minimal impact on the outcome of the 2016 U.S. election, the 2019 European elections, the rise of populism, and COVID-19 vaccination rates.10

Again, the results of the U.S. 2020 Facebook and Instagram Election Project support these findings. A reduction in misinformation was not associated with a change in political polarization, voting behavior in the 2020 U.S. election, or belief in election misconduct.

In 2023, a trio of authors — Sacha Altay, Manon Berriche, and Alberto Acerbi — examined the current body of research on misinformation in their article, Misinformation on Misinformation: Conceptual and Methodological Challenges. The results underlined the substantial disconnect between public perception and empirical results:

Concerns about misinformation are rising the world over. Today, Americans are more concerned about misinformation than sexism, racism, terrorism, or climate change…Yet, the scientific literature is clear. Unreliable news, including false, deceptive, low-quality, or hyper partisan news, represents a minute portion of people’s information diet. Most people do not share unreliable news. On average people deem fake news less plausible than true news. Social media are not the only culprit. The influence of fake news on large sociopolitical events is overblown.

Fake news is not good! But the magnitude of the threat may be smaller than many people perceive.

Nonetheless some experts in the Misinformation Survey believed that misinformation played a decisive role in the 2016 U.S. election. However, note that political scientists — presumably the most educated group on this particular topic — largely disagree with that characterization.

Generative AI: The next frontier in social media misinformation?

Applying the above lessons, even though Generative AI might amplify the quantity and sophistication of political misinformation on social media, its tangible effects in the real world may still be minimal. This can be attributed to three main factors. First, the majority of users primarily engage with social media for entertainment, not political discourse. Second, exposure to misinformation is limited to a small segment of social media users. Third, it appears that political misinformation on social media doesn't significantly sway political attitudes, beliefs, or voting behaviors.

Nonetheless, experts in the Misinformation Survey largely agreed that numerous changes are needed to curb misinformation on social media. Many of these changes would likely impact both human and AI-generated misinformation and, in fact, many have already been implemented. For instance, as we’ll discuss later, the idea of crowdsourcing misinformation detection is already in practice at Twitter and has helped detect numerous AI-generated images.

Potential threats of Generative AI

In January of 2023 OpenAI released a report on Generative Language Models (think ChatGPT) and the potential of automated influence operations, including on social media. Historically, these influence operations have been undertaken by malicious actors with the goal of using deceptive techniques to sway the opinions of a target audience. These campaigns include the use of both misinformation and psychologically manipulative tactics. For instance, during the 2016 Presidential Election social media accounts managed by Russia’s Internet Research Agency (IRA) pretended to be Black Americans to discourage members of the Black community from voting for Hilary Clinton.

According to Facebook’s own data there were more than 150 influence campaigns worldwide between 2017 and 2020. This has included both domestic and foreign attacks.

With the evolution of AI language models, these campaigns could become more sophisticated, assessing real-time sentiments and tailoring misinformation tactics that are virtually indistinguishable from genuine human interactions.

In a study released in April 2023, titled “The Potential of Generative AI for Personalized Persuasion at Scale,” researchers explored how effectively GPT-3 could scale tailored persuasive messaging. Some messages that were tested focused on product sales, but one such message centered around the topic of climate change. As part of their study, researchers had participants first take several assessments, pinpointing aspects of their personality and moral leanings, like tendencies toward introversion or extroversion. Using these insights, GPT-3 was tasked with formulating persuasive messages aligned with each participant's unique personality. The study's findings, while preliminary, suggest that language models might be adept at crafting effective personalized messages. Though this research required a direct assessment to understand a participant’s personality, future applications of Generative AI might deduce such details autonomously from an individual's social media activities.

Facebook has made clear its intention to harness Generative AI for advertising. In a discussion with Nikkei Asia, the company's CTO, Andrew Bosworth, shared plans to roll out tools that leverage Generative AI for ad creation. The envisioned technology would empower advertisers to customize imagery based on their target audience, reflecting Meta's confidence in the persuasive capabilities of Generative AI. Yet, the same technology could also be weaponized by malicious entities to launch tailored misinformation campaigns like those of Russia’s IRA.

Beyond text: AI's visual misinformation potential on social media

It’s possible that as text-to-video advances it will also be a possible method to spread misinformation. While the OpenAI influence report mentioned earlier focused on the automation of influence campaigns via language models, these concerns also extend to Generative AI text-to-video technologies. YouTube videos were a key attack vector for the IRA in their campaign to disempower Black voters. In fact, IRA created more than 1,100 YouTube videos as part of this campaign. With Generative AI capabilities, there's a heightened potential to craft convincing manipulative video narratives on an even larger scale.

It's not just videos that warrant concern. The meme culture, prominent on many social media platforms, has been harnessed for misleading political campaigns. During the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election, campaigns such as #DraftMyWife and #DraftOurDaughters were orchestrated to misleadingly associate Hillary Clinton with draft reinstatement concepts. As Generative AI continues to develop, the automation and personalization of such content could become more prevalent and potent.

Generative AI tools like Supermeme are pioneering the move towards automation, with features like their text-to-meme generator. At present, users must select a meme template. However, future advancements in text-to-image technology might enable the automatic creation of images, which can then be further refined in combination with AI language models to complete the meme. Alternatively, a multi-modal AI agent could select its own base image from a predefined set of well-known visual tropes.

Countering AI-enhanced misinformation on social media

To combat misinformation and influence campaigns on social media, several strategies have been proposed. Among these is the "proof of personhood" concept, suggesting additional authentication before a user can post. This could range from confirming an email address, to recording a video selfie, or even submitting a valid ID. Requirements for such verification could even escalate to include biometrics. However, balancing proof of personhood, customer privacy, and ease of use could be challenging. Moreover, resourceful malicious actors can potentially circumvent these measures. Advancements in Generative AI may further complicate this; for example, mature text-to-video technologies could easily sidestep video selfie authentications by creating fake, realistic selfies in seconds.

One interesting solution in this space is human identity provider Proof of Humanity, which creates a social identity system using everyone’s favorite technology: blockchain-based cryptocurrency. While Web3 applications — those utilizing blockchain and cryptocurrency — are now somewhat out of fashion, they could be revived to aid in a public ledger of human identity.

One proactive approach social media platforms could take is amending their terms of service to mandate the disclosure of AI-generated content. Moreover, they could actively flag or even remove accounts disseminating unauthorized AI-generated materials, especially if the intent is political manipulation or misinformation propagation. In fact, this isn't a novel concept; Facebook released such a policy back in 2020 as has TikTok. Future collaboration between AI technology providers and social media platforms could streamline detection efforts, as they can pool resources and expertise to identify suspect content.

Yet, the constant evolution of Generative AI poses a formidable challenge: as these systems become more sophisticated, detecting their outputs might become increasingly intricate. This task becomes even more daunting within encrypted social media platforms like WhatsApp and Telegram, where content surveillance is inherently limited, rendering traditional detection methods virtually ineffective.

These encryption-based apps can be important conduits for misinformation. For instance, threat actors based in Iran initiated disinformation campaigns targeting Israel, aiming to stir up opposition against the government of former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. These Iranian entities strategically opted for smaller, more private networks to sidestep the preventive actions of major social platforms such as Facebook.

Various other solutions can be explored to address the AI-generated misinformation risk. This could involve measures to clearly label AI-produced content, thereby providing transparency to users. Digital provenance — attaching a digital history record to AI-generated media — is a solution that has gained traction recently and has the support of major technology companies. Automated fact-checking could also be integrated, using advanced algorithms to swiftly identify and challenge dubious information. Each of these potential remedies, along with others, will be discussed in greater detail later in this article.

On a broader scale, digital literacy campaigns can empower individuals with the knowledge and skills to critically evaluate online content, discerning factual information from fabricated narratives.

Generative AI: The dual-edged sword in social media

While the primary focus here has been to highlight the risks and mitigations of Generative AI in the misinformation domain, it's crucial to remember that like any tool, its applications can be both benevolent and malicious. Beyond its potential for misinformation, Generative AI also holds promise in various positive domains, from entertainment and comedy to creating educational content tailored to specific audiences. For instance, tailored educational videos could provide personalized learning experiences, authors might use it to help write short stories, and comedians might use it to craft unique content for diverse audiences. Social media platforms are ideal channels for this kind of worthwhile AI-generated content.11

Indeed, recent research suggests that Generative AI can already match or surpass human creativity. For example, GPT-4 has been shown to score higher than 91% of humans on the Alternative Uses Test for creativity and exceed 99% of people on the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking. This prowess was further validated in two August 2023 studies where AI demonstrated superior capabilities in some dimensions of business idea generation compared to most human counterparts.12

A third study, whose preprint was also published in August 2023, offers further evidence that AI can elevate human creativity. In this investigation, over 200 writers were split into two groups: one composed narratives solo, while the other had AI assistance. Evaluators then blindly assessed the stories’ overall creativity based on criteria such as originality and uniqueness. The results were telling: stories crafted with AI guidance consistently outscored their human-only counterparts. This study not only underscores the potential enhancement of human creativity with AI collaboration but also hints at a future where standalone AI content might resonate deeply with human audiences.

Yet, the multifaceted utility of Generative AI introduces its own set of challenges. If platforms were to implement blanket policies labeling all AI-generated media, it risks stigmatizing all such content, irrespective of its intent. Positive and innovative AI-driven content could inadvertently be cast under the shadow of suspicion, grouped alongside misinformation. Hence, the challenge is not just about curbing the risks but also about ensuring that the myriad positive potentials of Generative AI aren't stifled or stigmatized in the process.

4. Dynamics of Generative AI-driven misinformation: The influence of political elites

While social media is often blamed for the spread of misinformation, it's crucial to highlight that political elites — politicians, political activists, and media personalities like political pundits — also play a significant role.13 In the Misinformation Survey experts agreed that more offline media was in need of study.

The credibility of political elites: A misinformation amplifier

Given their perceived credibility and extensive platforms, political elites can significantly influence the proliferation of misinformation. Their perceived “credibility factor” enables them to effectively disseminate false information, either by distorting the truth for political gain or shaping narratives.14

In the United States distortions by politicians include the assertion that the 2020 election was “stolen,” a claim primarily amplified by Republicans.15 Conversely, some Democratic figures have propagated the misleading narrative that billionaires are taxed at lower rates than teachers or that Trump tax cuts played an outsized role in the federal deficit.

Additionally, political pundits frequently amplify misinformation through their media platforms, often promoting unverified narratives that conflict with true events. An example from the Democratic side includes false claims that President Trump did not encourage U.S. citizens to get vaccinated. Conversely, misinformation from Republican pundits includes incorrect assertions that Democrats encouraged citizens to vote without registering. These practices not only spread misinformation but also potentially serve to further polarize the political landscape.

Two well-known studies have looked at the impact of Fox News on viewer behavior. One study — examining the now somewhat dated 1996 and 2000 Presidential elections — estimated that the introduction of Fox News to a town resulted in an additional 3% to 8% of viewers voting republican. Another study found a possible association between Fox News viewership and decreased compliance with COVID-19 social distancing guidelines. While these studies do not explicitly focus on misinformation, they underscore the importance of traditional media, expanding the conversation beyond the current focus on social media.

Generative AI and political elite misinformation

For all of the reasons mentioned above, the potential for U.S. political elites to purposefully or inadvertently promote AI-generated images, videos, or voices depicting harmful fictitious events could present a significant concern. The credibility associated with these figures can magnify the negative impact of such misinformation.

This situation is not merely hypothetical; there are several documented instances of U.S. political figures sharing AI-generated content:

In June of 2023 Ron DeSantis, the governor of Florida and a contender for the 2024 Republican Presidential nomination, shared AI-generated images of former President Donald Trump hugging Anthony Fauci. The intention behind this sharing was seemingly to undermine Trump's handling of the Covid-19 outbreak. It appears the DeSantis campaign shared these AI images knowingly. (See below).

Former President Donald Trump shared an AI-manipulated video of CNN host Anderson Cooper on his Truth Social platform, distorting Cooper's reaction to a CNN town hall event.

The Republican National Committee (RNC) released a dystopian campaign ad featuring a series of AI-generated images depicting a grim future under President Joe Biden's leadership. These images included an under-attack Taiwan, boarded-up storefronts in the United States, and soldiers patrolling local streets. (See below).

An AI-doctored video of Biden appearing to give a speech attacking transgender women and images of children supposedly learning satanism in libraries was circulated by unknown sources.

An AI-generated photo was shared by former President Donald Trump on his media platform, Truth Social. The photo depicted the former president kneeling in prayer. (See below).

AI images of former President Donald Trump being arrested were also circulated online by unknown sources. (See below).

Misinformation from political elites is not confined to the United States. Writing in The Guardian, political analyst Catherine Fieschi sharply critiqued European leaders:

In France, Marine Le Pen lies about how her party spends public money and her (fake) Twitter accounts. Viktor Orbán, the Hungarian prime minister, lies gigantically and systematically about the migration to his country. As for Italy’s Matteo Salvini – from migration to sanctions against Russia – as the song goes, if his lips are moving, he’s lying.

Potential risks of AI-Generated content in autocratic regimes

AI-created misinformation may pose heightened challenges in certain regions, for instance in East and Southeast Asia,16 where the rule of law may not be as robust. In these areas, political misinformation serves a dual purpose: as a powerful tool for propaganda campaigns orchestrated by autocratic regimes and as a convenient pretext for justifying authoritarian crackdowns.17 For example, Malaysia implemented a "fake news" ordinance, imposing severe penalties, including up to three years in prison, for disseminating false information related to Covid-19.

Within such environments, Generative AI technologies present potential risks on multiple fronts. Firstly, there is a concern that authoritarian regimes could exploit these technologies to advance their own agendas. They might utilize AI-generated content as a means to manipulate and control the flow of information, propagating misinformation to serve their interests.18 Though concerning, this possibility is still speculative as far as Generative AI technologies are concerned. Political scientist Eddie Yang has argued that a “Digital Dictator’s Dilemma” could arise in autocratic regimes. In this scenario, citizens' strategic withholding of information could limit the usefulness of Generative AI for repressive purposes.

Conversely, there is another possible scenario where governments may resist or reject the adoption of Generative AI as a measure to exert control over information that opposes their agenda.19 Such a broad, restrictive approach by authorities might hinder innovation in the AI field, which could, in turn, have negative effects on a country’s economic prospects.

Lastly, there’s the potential danger that misinformation from AI “hallucinations,” mentioned earlier, could deteriorate decision-making in autocratic regimes such as China.20 This could result in harmful public policies or even spur military engagement based on faulty data.

To help combat China’s rise as a global AI power, President Biden recently signed an executive order restricting certain U.S. investments in sensitive Chinese technology sectors, including some AI systems.

5. Misinformation distribution in the age of Generative AI

As highlighted earlier, Generative AI could itself evolve into a unique information distribution channel. Still, most discussions tend to view it primarily as a new means of creating content. This content — misinformation in this case — is then expected to spread through established channels, such as social media and political elites. Interrogating the intersection of Generative AI misinformation and existing distribution channels brings up four key sub-questions.

5a. Why haven’t we witnessed the anticipated negative impacts of Generative AI yet?

Much of the discourse around the potential harm of AI-powered misinformation tends to lean toward speculation and warnings of imminent dangers. The repeated refrain is "Just wait!" But what exactly are we waiting for? The leading text-to-image tool, Midjourney, already has a substantial base of approximately 15 million users and is readily available to anyone who wishes to utilize it for misinformation campaigns.

Prominent voices like Bill Gates have suggested that misinformers are simply biding their time, waiting for a crucial moment to strike. For instance, Gates mentions the potential for misuse during election cycles. U.S. Senator Chuck Schumer is more explicit, cautioning that AI could be used to undermine the credibility of elections as early as 2024. According to Schumer, we might soon see political campaigns deploying fabricated, yet believable images and videos of candidates, twisting their words and damaging their chances at election.

However, this perspective might be overly focused on the U.S. context. Elections are constantly taking place all over the world, and yet we have not seen a widespread use of AI-generated images or videos in misinformation campaigns in these regions. This lack of tangible evidence warrants further consideration.

Indeed, concerns about the potential impact of AI-manipulated content on the political landscape are not new. These fears were particularly pronounced leading up to the 2020 U.S. Presidential Election. In a 2020 article titled “What Happened to the Deepfake Threat to the Election?” Wired Magazine scrutinized the actual impact of deepfakes on the election outcome, noting the initial apprehension among many about the potential impact of deepfakes.

At a hearing of the House Intelligence Committee in June 2019, experts warned of the democracy-distorting potential of videos generated by artificial intelligence, known as deepfakes. Chair Adam Schiff (D-California) played a clip spoofing Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Massachusetts) and called on social media companies to take the threat seriously, because “after viral deepfakes have polluted the 2020 elections, by then it will be too late.” Danielle Citron, a law professor then at the University of Maryland, said “deepfake videos and audios could undermine the democratic process by tipping an election.”

But contrary to initial predictions by lawmakers and researchers, Wired reported that deepfakes did not significantly disrupt the vote. While there were instances of deepfake campaigns employed to raise awareness about the potential misuse of this technology — such as an ad featuring a fabricated Matt Gaetz and other videos spotlighting faux versions of Vladimir Putin (see video below) and Kim Jong-un — malicious deep fakes failed to tip the electoral scales. Despite the presence of deepfakes since 2017, their actual influence so far appears to be more modest than feared.21

Likewise, it could well be that the worst is yet to come for Generative AI, but if the threat is real it is still curious we have not seen more already.

5b. What distinguishes Generative AI from existing content creation technologies?

Political misinformation is far from a contemporary phenomenon. In my graduate studies, I once wrote a paper about how political propaganda, in the form of libelous pamphlets and illustrations portraying fictitious events, played into public sentiment towards Marie Antoinette during the French Revolution.

After President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, Thomas Hicks released a print that superimposed Lincoln’s head onto the body of John C. Calhoun in order to have a “heroic-style” picture of the President.22

Hicks’ doctored Lincoln portrait is just one example in the more than century-old history of fabricating images and videos depicting non-existent events or individuals.23 Advancements in technology have played a significant role in this area,24 with Adobe Photoshop emerging as a game-changer. In particular, Photoshop has revolutionized the field of digital photo manipulation, enabling the creation of highly convincing fake images with remarkable ease.25

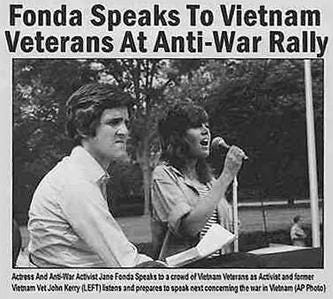

A prominent Photoshop example occurred during the 2004 presidential election campaign, when a fabricated image began circulating. This image falsely depicted Senator John Kerry alongside actress Jane Fonda at an anti-Vietnam War protest. The image garnered such widespread attention that it was even cited by The New York Times.

Even broadcast news reports have been staged to seem authentic. In 2006, for instance, a French-speaking broadcaster, RTBF, aired a breaking news report depicting Belgium's Flemish Region declaring independence. Footage of the royal family evacuating and the lowering of the Belgian flag added credence to the report. It was not until 30 minutes into the broadcast that a sign reading "Fiction" appeared on screen that the broadcast was revealed to be a hoax. Even then, many Belgium citizens were confused and nervous that the report was real.

Modern tools like Midjourney for text-to-image and Runway Gen2 for text-to-video generation may democratize the ability to generate or alter digital images or videos. But manipulating artifacts to falsely represent real-life events isn't novel. Those intent on creating digital misinformation have had capable tools at their disposal for decades.

Even Google has acknowledged the legacy of fake content in its guidance about AI-generated content, “Poor quality content isn't a new challenge for Google Search to deal with. We've been tackling poor quality content created both by humans and automation for years.”

Experts in the Misinformation Survey are split on whether misinformation is worse now than it was 10 years ago, suggesting that early Generative AI technologies have not yet had a definitive impact on the spread of misinformation.

While Generative AI may democratize the ability to produce misinformation, it’s worth recognizing that misinformation and media manipulation have been part and parcel of human communication for centuries. Advances in technology have certainly facilitated the production of false information, but they have not fundamentally changed this aspect of human nature.

However, Generative AI does represent a notable evolution in this realm. It automates and scales up the process of content creation, potentially making it more accessible and less time-consuming. This could democratize access to the tools of media manipulation, enabling a wider range of actors to engage in such practices. It also raises the specter of AI-generated misinformation being produced at a much larger scale than ever before.

Yet, despite these concerns, it remains unclear how this changing technological landscape will translate into a changing misinformation ecosystem. While Generative AI may raise the average quality and believability of misinformation, the impact on the top-end of misinformation — which is already quite convincing — may be less dramatic.

The assumption that Generative AI will lead to a transformational shift in misinformation distribution is based on a particular premise. It suggests that a significant group of people exists, intent on spreading misinformation for major objectives, such as election interference. Yet, for unidentified reasons, these individuals are currently restrained in spreading misinformation due to the technical photo- or video-manipulation skills required or the cost of hiring someone proficient. How probable is it that such a group exists? After all, as Gates identified in his blog post, misinformation often doesn't require high-quality fabrication to be effective — its power often lies more in the narrative it supports than in its technical execution.

Society has managed to navigate the challenges of misinformation in the past, even following the introduction of new technologies. This begs the question: why should we assume that we will be unable to do so in the age of AI?

5c. Will existing preventative measures help?

Social media platforms have implemented various measures to combat fake news, and these efforts have shown some degree of success. For instance, Facebook witnessed a decline in interactions with misinformation after 2016. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, YouTube introduced a “vaccine misinformation policy” to restrict the dissemination of videos promoting severe medical misinformation.

Twitter has incorporated a feature that enables crowdsourced fact-checking, leveraging the vigilance of users in identifying and flagging fake content, including instances involving Generative AI content. Notable examples include the swift detection of the viral “puffer coat photo” of The Pope, the AI-generated images of Donald Trump and Anthony Fauci posted by Ron DeSantis (mentioned earlier), and the debunking of the incorrect news story about AI causing the death of a drone pilot in a U.S. Air Force simulation (see below).

TikTok presents a complex scenario. As a platform popular among younger demographics, it has the potential to shape political views.26 Yet its ownership by Chinese parent company ByteDance raises national security concerns outside of strictly Generative AI considerations. Setting these concerns aside for the moment, it is worth noting that TikTok has recently updated its guidelines. Under the new rules, any content that uses AI to realistically depict scenes must be clearly marked as such.

That said, TikTok itself has recently released features like Bold Glamor and the “teenage look” filter, both of which appear to leverage Generative AI technologies (see video below). While not politically focused these filters do suggest TikTok’s openness to allowing Generative AI capabilities (they are also reportedly working on a Conversational AI).

There are also indications that society can adapt. For instance, one study found that “consumption of articles from fake news websites declined by approximately 75% between the 2016 and 2018 campaigns” in the United States.27

Existing measures to combat misinformation have shown some effectiveness, but the dynamic nature of Generative AI may cause these methods to decline in efficacy. If Generative AI media is of such high quality that social media platforms or crowd-sourced watchdogs cannot distinguish it from human-generated content, it may prove difficult to flag for removal. One potential avenue to aid in this effort is to use Generative AI itself to identify and fact-check AI-generated misinformation. This will be discussed more below.

5d. Will new preventative measures help?

In addition to existing measures, several emerging strategies to combat Generative AI misinformation are in development. These include industry-led initiatives that aim to provide guidelines for the use of Generative AI and synthetic media.

One such framework is the Partnership on AI (PAI), which is supported by prominent organizations including Google, Microsoft, Meta, OpenAI, TikTok, Adobe, and the BBC. The PAI offers guidance on key aspects of Generative AI use such as disclosing when an image is AI-generated and how companies can share data about these images.

Another initiative, The Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA) seeks to develop a unified technical specification other frameworks can adhere to. C2PA enables the attachment of a manifest to digital content, aiding in tracing its source and history and thereby providing a method to distinguish human and AI-generated media. C2PA is already supported by Adobe, Intel, Microsoft, the BBC, and Sony. One framework leveraging the C2PA technical standard is Project Origin, spearheaded by Microsoft and the BBC, which is designed to tackle disinformation in the digital news ecosystem.

After the Biden administration secured voluntary commitment from seven leading AI companies in late July of 2023, Microsoft, Anthropic, Google, and OpenAI launched the Frontier Model Forum to focus on improved AI safety. While misinformation was not explicitly called out, it is generally considered to fall under the umbrella of AI safety.28

Direct government regulation is also expected to play a significant role in this domain. In the U.S. the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has released an AI Risk Management Framework29 (AI RMF) aimed at promoting trustworthy use of AI.30 Congressman Ted Lieu, a democrat from Los Angeles County, has urged President Biden’s administration to require federal agencies to adopt the framework.

Other government-backed frameworks have been released as well. U.S. Senator Chuck Schumer, for instance, has announced a framework dubbed SAFE — an acronym standing for Security, Accountability, protecting our Foundations, and Explainability (see video below). This proposed framework could potentially serve as a legislative basis for the U.S. Congress to regulate the use of Generative AI.

These initiatives cater to the U.S. public’s growing desire for intervention to restrict misinformation. This includes public support for both government regulation and actions by tech companies themselves (see graphic below). The percentage of U.S. adults that want stronger misinformation restrictions in place has grown steadily over the past five years. This has been accompanied by a corresponding decrease in those with a preference for freedom of information.

Frameworks to curb potential Generative AI misinformation are not confined to the United States. For instance, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), made up of 38 member countries, has also released a framework for trustworthy AI.

Novel technologies specific to Generative AI, such as watermarking and image and video manipulation detection, also hold potential in combating misinformation. Although current techniques for watermarking AI-generated output are still experimental and need further refinement, they may prove promising. If perfected, these watermarking technologies could enable social media companies and other content providers to automatically flag or even remove AI-generated content. (See the video below for a discussion of watermarking Large Language Models like ChatGPT.)

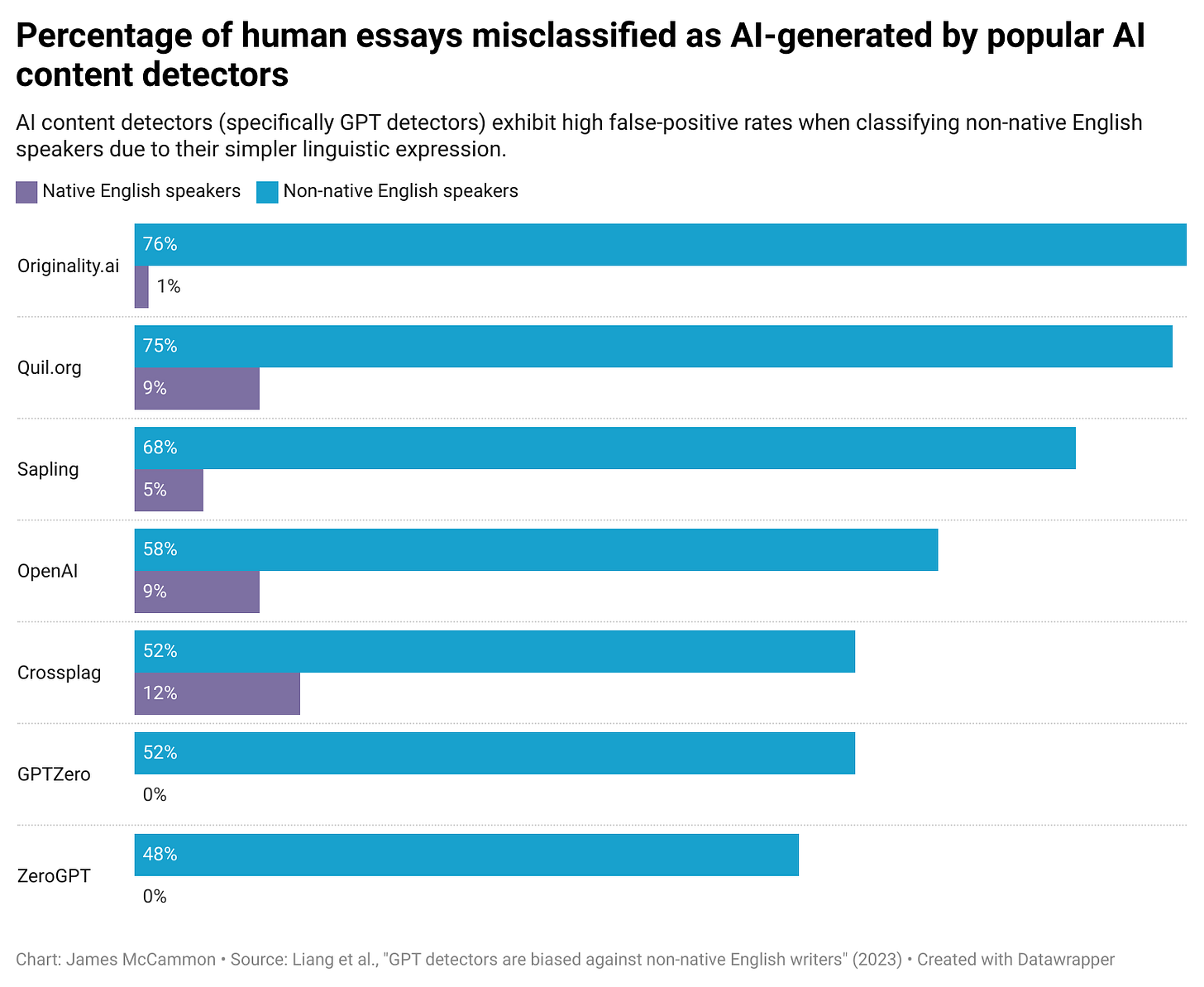

Another strategy to counter misinformation from Generative AI is the development of detectors that can reliably discern outputs from language models. Current AI detectors, though promising, still need significant refinement for dependable real-world application. A notable challenge is their heightened false-positive rates, particularly when analyzing content from individuals with limited linguistic expression, such as non-native English speakers. In this case, current detectors have false positive rates up to 76% (see chart below). Implementing these detectors without further optimization might inadvertently introduce a bias, wrongly flagging genuine content from this group as AI-generated misinformation.

A variety of technologies aimed at detecting deepfakes already exist, although their success rates vary. However, future iterations may prove to be more effective. Concurrently, there are tools under development designed to detect whether certain types of media, such as videos, have been manipulated. Forecasters at crowdsourcing market Metaculus predict a greater than 50% chance that a major Generative AI developer like OpenAI will be able to detect AI-generated content by the summer of 2024.

6. Generative AI and the evolution of fact-checking

As we’ve discussed, advanced Generative AI technologies carry the potential to create and propagate convincing yet entirely artificial narratives, images, and videos, contributing significantly to the spread of misinformation.

The global landscape of fact-checking

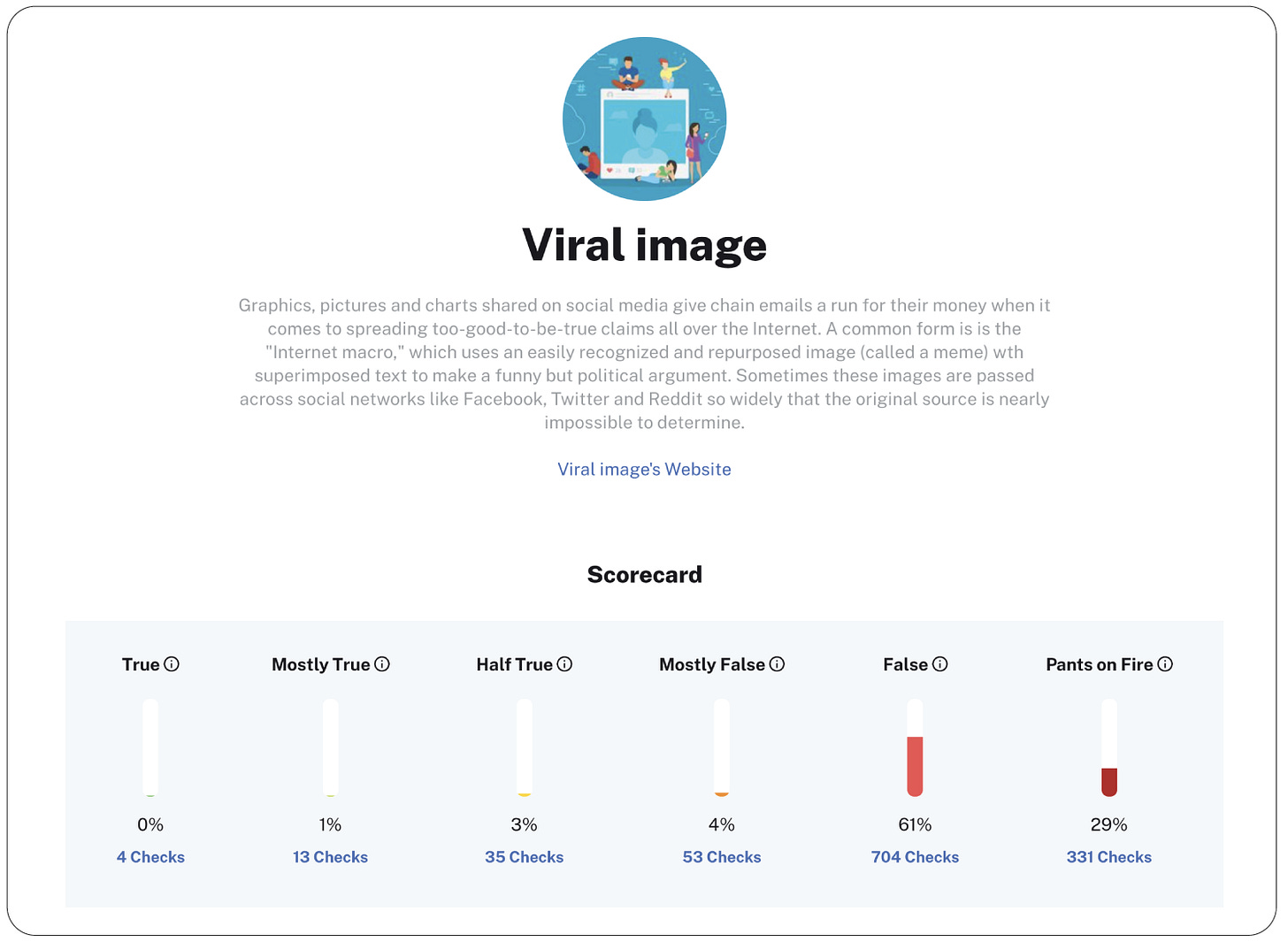

Outside of the efforts by social media companies discussed above, numerous U.S.-focused fact-checking websites such as Snopes, PolitiFact, and FactCheck.org have emerged to combat the spread of misinformation, including manipulated images. PolitiFact alone has fact-checked more than 1,000 viral images.

There is also a global network of non-U.S. fact-checking projects; for instance Africa Check, Chile Check, Ecuador Chequea, Debunk EU, Reality Check from the BBC, Digital Eye India, South Asia Check, and Taiwan FactCheck Center among dozens of others.

As just one example of the work these organizations do, the AI-doctored video of President Biden allegedly making negative statements about transgender women was fact-checked by an Indian website, Factly.

Challenges and potentials of AI-enhanced fact-checking

This rise of AI-generated content presents a daunting challenge, however, keeping pace with Generative AI, which can produce and disseminate misinformation with a speed and scale that human fact-checkers may find hard to match. As discussed previously, advancements in watermarking and deepfake detection could strengthen defenses against AI-generated misinformation.

Notably, Generative AI such as multimodal GPT models could potentially be employed to automate the process of fact-checking, verifying the authenticity of content quickly, or flagging suspect content for human review. A group of researchers recently tested this approach using GPT-3 Turbo, currently used in the free version of ChatGPT. They fed the model a total of 800 claims that had previously been fact-checked by humans and asked the model to label the claims as “true,” “false,” or “no evidence” given its existing knowledge base. The accuracy of the model was about 25 percentage points better than random guessing, indicating the model had some use, but needs improvement to be classified as a robust fact-checking tool. As Generative AI technologies continue to improve (ex. GPT-4) and become connected to the internet this may further improve their accuracy and utility in this arena.

However, the effectiveness of AI in fact-checking and debunking misinformation isn't without challenges. Bridging the gap between individuals encountering misinformation and corresponding fact-checks is a significant hurdle. Not all consumers actively seek out fact-checking resources.31 This fact-checking mismatch could become problematic if AI-generated images or videos become highly realistic and abundant. The effectiveness of corrective information can also be moderated by factors like the political polarization of the issue at hand.32

Nevertheless, research suggests that debunking misinformation is generally effective.33 Detailed, non-political corrections seem to have a higher impact, especially when the subject is familiar with the topic.34 In the realm of social media, one study of TikTok debunking videos showed a mild positive impact on viewers’ ability to distinguish a false claim as misinformation and well as diminished belief in the false claim itself.

The prevalence of debunking videos on TikTok brings up the idea that Generative AI could automate the production of debunking videos. By leveraging AI's capacity to sift through vast amounts of data rapidly, it could identify trending misinformation in real-time. Upon identifying a falsehood, the AI could cross-reference it with credible data sources, and then generate a script that highlights the discrepancy.

Subsequently, utilizing the advancements in Generative AI capabilities, the system could create digital assets like animations, infographics, or even synthetic human-like narrations, resulting in a comprehensive video debunking the misinformation. The system could also tailor the video's format and style to be most suitable for various social media platforms, ensuring maximum reach and engagement.

A team of researchers recently piloted just such a tool called ReelFramer (see screenshot below). The tool employs generative text and image capabilities to assist journalists in crafting various narrative perspectives for short-format stories, such as those seen on TikTok and Instagram Reels. With ReelFramer, journalists can automatically produce a story, complete with scripts, character boards, and storyboards. These generated elements can then be modified and refined further. In a user study involving five graduate journalism students, it was found that ReelFramer significantly simplified the process of converting written content into a visual reel. Future Generative AI technologies might help further automate this process, potentially extending similar technologies to include longer-form content.

Generative AI could also facilitate fact-checking processes. By cross-referencing claims made in articles or social media posts with trusted databases of factual information, Generative AI could expedite the identification and correction of misleading or false information.

The key here is the machine's ability to process data on a scale that is beyond human capabilities, thus offering a bird's-eye view of the misinformation landscape. This capability is likely to be particularly useful in the context of online spaces, where information spreads rapidly and is frequently manipulated or distorted.

Some researchers have expressed concern that providing debunking or fact-checking corrections might inadvertently cause “backfire effects,” diminishing trust in true news.35 This has included worries about the impact of general “fake news” warnings36 or that misinformation warnings from political elites may breed uncertainty in true news.37 Additionally, the simple repetition of false content — once in its original form and then again during debunking — has been hypothesized to lead to a “familiarity backfire effect.”38 If backfire effects are substantial then Generative AI’s contribution to debunking may be ineffective or even exacerbate the misinformation problem. However, newer research suggests the backfire effect is likely small if it exists at all.39

Finally, Generative AI could prove instrumental in unraveling the intricacies of online misinformation's origins and propagation, thereby empowering more targeted and efficient interventions. For example, by training these systems on vast amounts of data, researchers can identify patterns and trends in misinformation dissemination. By recognizing the common narratives, tactics, or themes used in disinformation campaigns, Generative AI can aid in the early detection of these campaigns.

Such AI tools can then, in turn, aid in the development of proactive strategies to counteract misinformation before it spreads widely. For instance, AI-generated alerts could be used to notify social media platforms or news outlets about emerging disinformation trends, enabling them to act swiftly to mitigate their impact.

Overall, while Generative AI does present new challenges in the battle against misinformation, it also offers innovative solutions. The ultimate impact of these technologies will likely depend on how they are developed and implemented, as well as the policies and regulations that govern their use.

The four studies are: 1.“Like-minded sources on Facebook are prevalent but not polarizing.” 2. “Reshares on social media amplify political news but do not detectably affect beliefs or opinions.” 3. “How do social media feed algorithms affect attitudes and behavior in an election campaign?” 4. “Asymmetric ideological segregation in exposure to political news on Facebook.”

But not necessarily compelling from the results of the study itself.

This kind of seems like a silly example. Even today with knowledge of the current state of AI would responsible news outlets run such an unverified story the morning of an election? What percentage of voters watch the news the morning of an election? Given the current state of AI how many voters would believe the video is authentic if viewed? Given the current state of AI even if the video was authentic how many people would believe the video is genuine? Isn’t the morning of an election a suspicious time to drop such a video?!?! That seems as if it would remove credibility not add to it.

See “Misperceptions about others” for a meta-analysis of 51 global studies that measure misperceptions.

See “What makes a tax evader?” The authors note that, “We study all 151,565 taxpayers in the country who earned wages and filed a tax return in 2016. We find that 15.5% of them under-reported their wages…” Survey details can be found in section 4.4.

The perceived rate of evasion can be found in Table A.1 of the online data appendix; the average for the Workers’ Evasion question was 3.506. The authors describe the Workers’ Evasion question as follows: “After a brief explanation on how employees may under-report wages, we ask individuals to guess the percentage of employees who under-report their wages using bins from ‘0-10%’ to ‘90-100%’.” A score of 3 corresponds to the third bin, 20%-30%, whereas a 4 corresponds to 30%-40%. Therefore an average of 3.5 for the Workers’ Evasion question means that on average survey respondents perceive the tax evasion rate to be approximately 30%. This is an overstatement of about double (i.e. actual is evasion rate is 15.5% but the perceived rate of evasion is about 30%).

See Figure 2 in “Beliefs about Climate Beliefs: The Importance of Second-Order Opinions for Climate Politics.” Survey methodology details: “Sixth, and finally, we also fielded questions in a nationally representative internet-based survey of the Chinese public in February 2015, again using the firm Survey Sampling International (n=1,659). This survey used quota sampling procedure to achieve an approximately nationally representative sample based on gender, age, and region in China. The survey was translated from English to Mandarin by native speakers and then back-translated. Differences between the questions asked in the Chinese and US surveys are detailed in the following section.”

See Table A-2 “Perceptions of Immigrants by Country” in “Immigration and Redistribution.” In the UK, the actual rate is 19%, but in a nationally representative survey, respondents perceived it as 29%. In France, the actual rate is 24%, but in a nationally representative survey, respondents perceived it as 42%. In Italy, the actual rate is 35%, but in a nationally representative survey, respondents perceived it as 43%. In Germany, the actual rate is 20%, but in a nationally representative survey, respondents perceived it as 34%. However, Sweden diverged from this trend: its actual rate of 30% was underestimated, with respondents perceiving it to be 25%. See section 2.1 for survey methodology.

Twitter notes that during the 2020 election 74% of people who viewed misleading election tweets did so after Twitter had applied a label denoting the tweet as such.

However, note that not all domains or URLs on Facebook are evaluated by Meta’s Third-Party Fact-Checking Program due to the large volume.

In the United States, for instance, 92.3% of those over 18 got vaccinated. That’s higher than rates for many other viruses including tetanus (Td and Tdap), Hepatitis A Vaccination, Hepatitis B Vaccination, and Human Papillomavirus Vaccination (HPV) [source here]. COVID-19 vaccination rates were on par with MMR and polio vaccine rates. For the MMR vaccine, 91.9% of those 13-17 years were vaccinated; I’m assuming few people waited until age 18+ to get vaccinated which means the adult vaccination rate is likely stable around 29% - 93%. For polio, 92.5% of those 24 months or younger received the vaccine; again assuming most people who will receive the vaccine will have done so by that age, the figure is comparable to COVID-19 vaccination rates.

To highlight just one study in this area, “Digital Media Use and Adolescents' Mental Health During the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis” reviewed previous research on adolescent social isolation during the Covid-19 outbreak and found, “In particular, one-to-one communication, self-disclosure in the context of mutual online friendship, as well as positive and funny online experiences mitigated feelings of loneliness and stress.” [Emphasis added].

For a general discussion of the Fox New’s impact on political views see “The Fox News Effect: Media Bias and Voting” and “The Persuasive Effect of Fox News: Non-Compliance with Social Distancing During the Covid-19 Pandemic.”

For instance, one-third of Americans still believe that President Joe Biden won his 2020 election only due to voter fraud.

Purveyors of these claims include President Trump himself. An analysis by The Washington Post found that by one measure Trump made more than 30,000 false claims during his four years as president. See also “Trump’s Lies vs. Obama’s” by The New York Times.

For examples, see “Impact of disinformation on democracy in Asia” by The Brookings Institute or “Southeast Asia’s Disinformation Crisis: Where the State is the Biggest Bad Actor and Regulation is a Bad Word” by The Social Science Research Council.

See “Fake News Crackdowns Do Damage Across Southeast Asia During Pandemic” by Center for Strategic and International Studies.

For a balanced discussion of China’s AI policies see, “China’s New AI Governance Initiatives Shouldn’t Be Ignored” by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

For instance, see “China announces rules to keep AI bound by ‘core socialist values’” in the Washington Post.

See the second scenario discussed in Pathway 2 in “U.S.-China Competition and Military AI.”

Wikipedia has a good list of real-life applications of deepfakes which have caused harm.

For more see the Atlas Obscura article, “The Great Lengths Taken to Make Abraham Lincoln Look Good in Portraits.”

For more examples see: NPR’s article, “A Very Weird Photo Of Ulysses S. Grant.” The New York Times slideshow, “A Brief History of Photo Fakery.” Wikipedia’s “List of photograph manipulation incidents.” This photo and this photo from the Library of Congress archives. The article, “44 famous Photoshopped and doctored images from across the ages” from Pocket-lint.

See “The Time-Travelling Camera: A Short History of Digital Photo Manipulation” from the Science and Media Museum.

For a humorous set of high-quality Photoshop images see this collection of images from Average Rob.

The article "Scrolling, Simping, and Mobilizing: TikTok’s influence over Generation Z’s Political Behavior" serves as the main reference I could find for TikTok's potential influence on political behavior. However, this article exemplifies a trend I’ve noticed in which the paper’s title outshines the substance of the work. While the paper discusses the potential political impact of TikTok, the supporting evidence provided within it is relatively weak, hence my use of the term "potential to shape political views."

Nonetheless, the hypothesis of TikTok’s influence may be correct. We know that more young adults are getting their news from TikTok (see these results from the Pew Research Center), so it stands to reason this news consumption might have an impact on political views.

See “Fake news, Facebook ads, and misperceptions† Assessing information quality in the 2018 U.S. midterm election campaign” which notes that: “In fall 2016, 27% of Americans read an article from a fake news site on their laptop or desktop computer. The mean number of articles read was 5.5, which made up 1.9% of pages that Americans visited from websites focusing on hard news topics. In fall 2018, however, only 7% of the public read an article from a fake news site. On average, people read only 0.7 articles from these sites, which accounted for just 0.7% of the public’s news diet. In other words, the proportion of Americans consuming fake news and their total consumption of articles from fake news websites declined by approximately 75% between the 2016 and 2018 campaigns.”

For example, the AI safety Wikipedia page lists “disinformation” as an area of AI governance.

Brookings has a good background explainer on the framework.