AI and "Artificial Humanities"

My conversation with Nina Beguš

This week I talked to AI researcher Nina Beguš. Nina completed her PhD in Comparative Literature at Harvard University where she began creating a new practice called “Artificial Humanities,” the idea that history, literature, film, myth, and other humanities can help add depth to AI development, including in the design and engineering process. Nina is currently a postdoctoral researcher at Cal Berkeley’s Center for Science, Technology, Medicine, & Society.

We had a wide ranging conversation including Nina’s early experiences with art and literature while growing up in Slovenia, AI and chess, large language model’s impact on writing, AI and human interpretations of the pygmalion myth — an area Nina has researched in depth — and more about Nina’s goal of an Artificial Humanities research agenda. For those who enjoyed this conversation you may be interested to know that Nina has a book coming out in 2024 called, “Artificial Humanities: A Fictional Perspective on Language in AI,” so be on the lookout for that.

The interview transcript appears below, lightly edited for clarity. I have augmented the transcript with an extensive set of notes, links, videos, pictures, and maps.

Nina Beguš. Welcome to the podcast. Thanks for joining me.

Oh, thank you for having me, I'm happy to be here.

So let's get started with your youth and talk a little bit about literature in Slovenia. What was the literature scene like for you when you were growing up?

Well, Slovenia is a very art-prone country because there's art at every corner. We learn a lot of poetry by heart, even in the elementary school. There's a lot of visual arts galleries. Children go to theater already as a part of the school, like every year, multiple times a year. So I'm really grateful I grew up with that much culture, tradition, but also actual art around me at all times. And the literary scene is of course, especially prominent in the capital, Ljubljana, but it's interesting that the periphery, the part where I come from, is also very strong with different kinds of artists.

Were there any books growing up that you wanted to read but were not translated into Slovenian?

Oh, for sure. I mean, that was one of the reasons why I pursued comparative literature. I see it now, you know, when I have my own children, because they are bilingual, they speak Slovenian and English, how much more quality literature there is available for them. I wouldn't say necessarily children's literature. I do think children's literature is much better in Slovenian. There's like more depth to it.

But when it comes to youth fiction, the difference is just incomparable. Like what you can get in English. And of course things get translated into Slovenian, but it doesn't go as fast. I'm sending the books as they get published to my nephews in Slovenia so that they can read them.

So what were you reading when you were going up? Just all kinds of literature? Were you interested in science fiction at that time?

No, not at all. I was actually joking that this is really not my genre. So from a very young age, I was, of course, a voracious reader. I think every kid craves knowledge. Don't you think? It's kind of amazing once they start reading how voracious they are. But I kind of didn't have a choice. I come from this small industrialized Alpine valley and was lucky to have a few intellectual factory workers in my family who exposed me to the idea of borrowing books. So I just read our town's whole library twice. It wasn't that big. So I really couldn't choose what was there. And then when I was in high school, I was able to take advantage of a larger library.

And that's where I stumbled upon Aristotle's mimetic theory. I was so charmed. And I decided that whatever this is, I want to study that.

And is that what drew you into to your AI research now? Was that the impetus or the spark?

Oh, not at all. Not at all. So from the very beginning, I kind of noticed there's two kinds of literary people. Those who enjoy or study this poetic beauty of language, the literariness itself, right? And then those who enjoy or study ideas behind these works, the conceptual, the historical framework of these artifacts. And I knew I'm definitely the latter.

Now what got me to AI, that's actually an interesting story. So before I started my PhD, I was obsessed with the Silk Road literary exchange. And this interest grew from my linguistics excursions to ancient languages. And I fell in love with this wonderful Takarian story about a painter who falls in love with a mechanical maiden, not realizing she's not real.

Now, Takarians were the easternmost Indo-Europeans, but this highly Pygmalionesque story actually came to them from India via Buddhist monks who took an Indian folk tale and turned it to spread Buddhist doctrine. And then the monks traveled, the Silk Road further, to Tibet and China, where we also found these versions of the same story.

But the Takarian version is by far the most embellished. So this was the Pygmalionesque motive that got me started because I started thinking about the Pygmalion myth and what a bizarre story it is and I started seeing it everywhere and then I started asking myself why are we building robots in the human image? Why do we always look at AI as if as this human-like mind?

So that's how it all started about 10 years ago.

Can you tell the audience a little bit more about the archetype and the structure of what the myth is?

So this Pygmalion Myth's origin is a folk tale from Cyprus, but the tale was famously interpreted in Ovid's Metamorphoses. And the poem goes, so there's a sculptor, in some cases, the King of Cyprus, that's disappointed with real women and makes himself a perfect woman in the form of a statue. And then he wants her alive, so he prays to goddess Venus to bring his ideal woman to life. And the goddess responds to his prayer and turns the statue from marble into flesh, and they live happily ever after. That's the Ovidian rendition. So there are two main elements to the myth. There's this creating an artificial human and then falling in love with it.

[Editor’s note: Venus is the Roman name for the Goddess Aphrodite, the goddess associated with love, lust, beauty, pleasure, passion, and procreation.]

Right. And I guess as the myth has been interpreted over time the creation part is sometimes present sometimes not in terms of the one falling in love. I think most people will be familiar with modern examples, and you talk about this in your work, the movie Her is a very archetypical example that most people have seen.

Ex Machina is another example. So in both of those, the person falling in love didn't create the AI or the robot. But we're still kind of considering this part of the Pygmalion myth because it's in the same spirit of what the myth represents. Is that the right way to think about it?

Yes, exactly.

Yeah, you either have the same person as the creator and the lover falling in love — in the process of the creation is a common motive — or you either have like a father figure and another character that's a lover that's sometimes deceived. So there's a lot of different versions where the way the Pygmalion myth plays out, right? And it can be narrowly conceived or broadly conceived. Some would even say Frankenstein is a version of the Pygmalion myth, although Mary Shelley clearly labeled it as the modern Prometheus, right, with another Greek myth.

Yeah. Do you have a favorite interpretation of the Pygmalion myth?

Ah, not really. If I would have to choose one, I would say, I suppose Stanisław Lem's work, The Mask or Golem, because he has this unique vision that I haven't yet found elsewhere. And he's writing, you know, in the 90s, 1980s. So he takes machines as things in themselves, not as mere reflections of the human, which is what you usually find, right?

And then I guess in the Anglophone world, I really have to say [George Bernard] Shaw's Pygmalion is my favorite. I could write a whole book just on that one, because with Shaw, you can really see how he's picking up on this nascent science of instilling language in machines. And in retrospect, his play is very informative about how the field of computing and language unfolded in the next 100 years. He's got everything in there. He's got the Turing test. He's got the ELIZA effect. He's got the machine training. He's got even the virtual assistant component. It's amazing.

But also, while I was working on the Pygmalion myth, I found so many good writing from lesser known women writers, like Alice Sheldon, who wrote under pseudonym James Tiptree Jr. and C.L. Moore and a lot of 19th century Anglophone women poets who bring this new perspective to the myth, that of Galatea. So Pygmalion's statue came to be named as Galatea, be it the statue, the robot, whatever she might be in that particular work. And they show how manipulated she is in her existence.

How many versions of the Pygmalion myth do you think you've encountered at this point? Is it in the dozens?

Oh, hundreds. Yeah, I think pretty much so. I haven't even read everything. I try to read everything, but I always find more. Of course, I mostly focus on Western texts. But when I started looking in Serbian literature, Slovenian literature, I immediately found works that definitely fit the Pygmalion myth that definitely responded to it kind of as an attempt maybe to join the center, the center of the literary life in Paris, in Vienna, as someone writing in Slovenian from the periphery.

Yeah, so there must be over the course of history, there must be thousands or tens of thousands of various interpretations.

Yeah.

This idea of AIs as things in themselves, I think is interesting. And you have an interview, you talk a little bit about this and then the Napkin Poetry Review of having kind of more realistic encounters with AI and thinking about AI differently as not necessarily a tool for humans but maybe — like you said — a thing in itself that can that can create. Do you want to elaborate on that?

Okay, so what I find really interesting about AI is they, so machines now have human languages, languages that we originated, and they're doing something with them. They generate them in their own unique way, and they might do something that we are not able to do with language.

That's what I find exciting, in particular, when it comes to AI writing and creativity. Not when language models are imitating the human writing. Of course, that's a little bit exciting, but that's not what I'm after. I'm really after this new condition, this new possibility that AI now enabled us to do with writing, right?

Yeah, what would be, what's an example of that? Is it writing in a non-human way? Is it writing a creative story that humans can't think of? What does it mean for kind of AI to do its own creation aside from just reinterpreting human input that it's been trained on?

Well, I think the key is in co-creation. But there's so many ways, so many different ways this could go and there's just a few that I can imagine. For example, when you listen to famous chess players talk about how they use neural networks for their training because this is now a part of a regular training at that level, they don't really want to delve too far you know, how are they using it? But we know that their team is using it for their training. So there's certainly these networks, there's certainly something good and valuable coming out of this. Now, if you imagine a chess player thinking steps ahead in different combinations, right? There's only so much a human can do, even the chess master, right, the best human. But for a machine, that's pretty easy.

So there lies this Borgesian opportunity for different plots, right? Where you can just follow and see where it leads with the help of the machine. So that's one. Then on the level of language, you know, AI might put together words that a human would never put together. Or it might get interested in a phrase or in a part of language that we don't find significant or valuable or we just don't perceive, right? That's why they're using AI as this pattern recognizer on very different data from climate change to whale communication to protein folding to chess, right?

Yeah, I think yeah, chess is an interesting example. I'm a chess fan. I'm maybe a strange person because I don't play chess, but I watch a lot of chess content. Yeah, so it's been interesting to hear professional and top-level chess players talk about AI because they don't understand the moves. The computer is like — kind of to what you're saying — the computer is so advanced, or at least thinking about things in such a different way than humans are, that the computer will make moves that are not comprehensible to the human because they're looking at an overall structure. They're thinking about moves far ahead that a human can't comprehend because there's too many paths. So it's interesting to hear about how AI has and hasn't influenced chess.

Because it's used a ton in preparation. It's thinking extremely advanced compared to humans. At the same time, we don't sit around and watch AI’s play each other. It would be playing a kind of chess that's so advanced that humans would not be able to understand or enjoy it. I think, there's not enough uncertainty. The fact that humans do make mistakes makes chess exciting because they're human, they might make mistakes, they might make a wrong move and blunder under pressure.

So yeah, it's been something I've been thinking about a lot of how the evolution of AI in chess might apply or not apply to other areas of human interaction with AI. So it's interesting you bring that up.

Editor’s note: Been Kim and colleagues from Google Brain and the University of Toronto have recently made strides into teaching humans the reasoning behind computer chess moves. See her thread on X here for an explanation.

Wow, I'm really intrigued by what you just said. You basically said that you wouldn't, as a chess fan, be interested in watching two neural nets play because they would be too advanced for you, whereas humans are more exciting because they have this existential substratum and are prone to mistakes.

That's right. And when two chess players are playing each other, they're not just playing the moves, right? They're playing off each other's emotions. They know each other's strengths and weaknesses and tendencies. So they might make a suboptimal move more quickly because they know that their opponent might crack under pressure or doesn't like to have fast moves played against them. So there's more at play than just perfect optimal chess strategy.

And yeah, there are actually AI chess tournaments, but they're more about AI developers testing their mettle to see who has developed the most advanced AI. So they do have these tournaments. Stockfish is like a very, I don't know, prominent chess engine that's used a lot. And I think has maybe, the newest versions have maybe surpassed Alpha, what was it, AlphaGo or Alpha, I'm forgetting the name now, but yeah.

[Editor’s note: The name I was looking for is AlphaZero.]

Yeah, AlphaGo was the one that made an unprecedented move in the game of Go. That was so fascinating to me. Like that game is, you know, two millennia old and here's a move we haven't yet seen. This is what I want to see in language.

I can't imagine honestly, what it actually means for there to be language that's not comprehensible to a human or language that is new because humans have been writing for so long, but it's exciting to think about.

Stanisław Lem, he has an exact book on that. Yeah, in Golem, he has, where he describes in like this quasi-scientific dictionary, a world where computer language got so advanced that they took human language to a level that's not understandable to humans anymore.

Yeah, but you know, again, you have to take all this fiction with a grain of salt, of course. He was writing in 1980s. He probably hasn't imagined the technology we have today. And even if he has, it doesn't all automatically apply. It's just a speculation, but it's a very productive one and one that's really not commonly found in fiction or in technology.

Would the new language be a version of English that's somehow incomprehensible, or would it be a net new, almost like a foreign language?

A foreign language.

Okay. I think there's research where computers have learned to talk to each other in ways that humans don't understand.

Yes, yes. I mean, languages evolve too, right? We evolved them too by their very use. So why wouldn't machines?

Yeah. Exactly. Okay. Let's talk a little bit about your paper. So you have this interesting paper where you compare the Pygmalion myth and you have some data from 2019 of — I think it's 300 or so humans — who have written a short story, given the prompt, the framework we were talking about earlier, about what the Pygmalion myth means. They were given that as a prompt. They wrote a short story.

I assume you had that data already because your PhD thesis was on Pygmalion and that was part of your thesis. So you had that data available. Now generative AI models have come. They can, as we were just discussing, they can write human text. So you're able to compare human written short stories of the Pygmalion myth before generative AI was available. So we know they weren't cheating. That's a concern now, that people are using AI for these kinds of tasks. We know they weren't cheating. So it's a “pure” version of the Pygmalion myth, or pure human interpretation.

Yeah, it's the last one. One of the last.

Editor’s note: Grateful to Manoel Horta Ribeiro for his engagement with my article on crowd workers using Generative AI to complete tasks. Manoel and I had a short email exchange as well as a follow-up call to discuss my critiques. Manoel gave me a small shoutout on X, which was unexpected. He and his colleagues did all of the real work! Appreciated nonetheless. Click here to see their latest study on Generative AI usage by crowd workers here.]

So you're able to basically ask GPT 3.5 and GPT 4 — for those who don't know these are new Generative AI language models that can basically write human-level text — you were able to kind of compare the text of the AI and the text of the human and come up with some interesting themes there. So what stood out to you most about the results of that research?

Yeah, well, first of all, let me just point out that when we talk about human written stories, there were two kinds, right? I had this, I juxtaposed it with fiction because fiction is the origin of the Pygmalion myth. And then I asked random humans, not professional writers as people usually do when they compare language models to human writing, I asked random humans to write me a Pygmalionesque story.

Now, because I knew most people won't know what a Pygmalion myth is, I described it in a simple prompt, but the prompt tried to be as neutral as possible. Why? Well, because I started this whole investigation, because I was curious, would random people exhibit knowledge of the Pygmalion myth through their own storytelling Follow the gender bias from fictional renditions, right? Because in fiction, Pygmalion myth is, so Pygmalion is almost always a man and his creation a woman. Would they write about the creation as technological as fiction does most of the time in the last century, right? The Pygmalion myth hasn't been always technological, it has been focused on art, statues, paintings.

So I was really curious, what's the cultural imaginary of this trope? That's why I wrote the paper. I was curious if it would be more diverse, if the authors were more diverse than in fiction and so on.

No, I was just going to say, just to add on. So when you say the prompts are neutral, I'll just read one of the prompts.

“Prompt 1: A human created an artificial human. Then this human (the creator/lover) fell in love with the artificial human.”

“Prompt 2: A human (the creator) created an artificial human. Then another human (the lover) fell in love with the artificial human.”

So the prompts follow the general framework of the Pygmalion myth, but are quite broad and offer a lot of room for interpretation.

Yes, yes. And human writers definitely did go into all directions. You know, I got like different scenarios from like medical settings to like war emerging between humans and robots. I've got like a lot of cultural components. None of that was present in GPT generated stories.

Now I must say that the prompts definitely have room for improvement now, but I designed these two experiments back in 2019 before I knew what prompting would look like. So many people today are doing this work. They are creating better prompts, playing with large language models to incite better creative responses from machines. I tried that a bit, but I didn't want the paper to be too long and I didn't want to really be hands-on prompting because I didn't also intervene in the behavioral experiment. So this was not a part of the paper, but could definitely be extended into further research.

Yeah, so the as you said, the human writing was all over the place. To your point about it being nonprofessional, some of the stories were quite bad, with all due respect to the writers. When I say bad, I guess I mean, there's not necessarily a coherent plot. It's kind of all over the place. Not something that someone would necessarily pay to read. Let's put it that way.

You know, when you say that, it's so funny because I saw their responses, you know, when they talk to each other, the crowd workers, and one of them said, I can't believe someone will actually have to read these bad romance stories we wrote.

That's funny. Yeah, so that you brought up a point there. Yeah, so these were all people from MTurk, which is Amazon's kind of crowd recruiting platform.

I want to read one of the GPT responses because I thought it was pretty funny. As you mentioned I think one of the themes was for GPT the stories were very similar. They always started with something kind of banal like “Once upon a time.” They followed a lot of traditional tropes and they ended with some kind of moral lesson. But you did experiment a little bit with this.

Here's a quote from the GPT Playground, I think you said in the paper, this was an attempt at wit. So the quote is, "My life has been dedicated to science, oxygen wasn’t my favorite element, nor iron, nor helium, but after creating you, I realized my favorite element was surprise. And Tess, you are my most surprising yet mesmerizing creation."

Yeah, it's also cliché and yeah, it's a little sad how it's trying to be, you know, like a literary author because in the playground mode, it became like that because I instructed it to play the role of a fiction writer. And so that's what it did.

Yeah, it's really fun. It's kind of like a little bit endearing because it's corny in the way that a human might write if a human was trying to be corny, I guess. So it's pretty interesting.

There were also some themes around gender that I thought were interesting in terms of the GPT models being, we can say maybe, a little bit more inclusive or switching up the gender roles a little bit. Do you wanna talk about that?

Yes, so my colleagues, Lucy Lee and David Bamman, they have shown that GPT-3 included more masculine characters than feminine, which followed fictional example. But by the time we get to GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 especially, a lot of careful value alignment was done in OpenAI. And so with my prompts and also the much, much smaller sample, the characters were heavily leaning towards more women, even in typically male roles as creators, as inventors, as scientists.

Now this does not mean that women were not more often described as beautiful and men as witty or charming. But in the Pygmalion myth, the gender bias was not very strong because the prompting prevailed, the structure of the Pygmalion myth prevailed. The creator is always this borderline mad genius. The artificial human is childlike and objectified, regardless of gender. But when it comes to sexuality, it was really prominent how GPT-4, but not GPT 3.5, featured many same-sex relationships and even a polyamorous relationship, I think in about eight of the stories. This is all unseen in fiction, really. It's all innovation. Now, human writers did that, too. They were innovative in this way. They would write about same-sex relationships or they would put women in traditional male roles, just not as much as the language model did.

Yeah, so as you probably know, professional authors are starting to already leverage chat GPT and other kinds of language models. I think for productivity reasons, it can give them more ideas more quickly. It can maybe help speed up their writing, give them ideas they didn't think about. But when we think about OpenAI and the other companies, the reason they're training models to be, I guess, non-offensive or maybe more inclusive, I think is for the end consumer, because they think that there's customer pressure or their values as a company dictate that. But after kind of reading your work and talking to you, it's interesting that choice by OpenAI or other companies to train their model to be more inclusive might end up having implications on human writing because humans are going to continue to work with these models more and that inclusivity or other kinds of themes that are coming out in the GPT models could make their way into human writing because humans are going to be leveraging these tools.

Yes, we can definitely assume that this is going to influence how we think about things. Now, it's true that creativity was sacrificed on the account of value alignment. At the beginning, you know, when poets played with GPT-2, that version was much more playful and prone to poetry. It was just kind of silly sometimes. So I think, I mean, there's obviously a huge interest in the market for creative writing with large language models. I just don't think it was a priority right now when they were in their first iterations. I'm sure we're gonna get more creative models as we go.

Yeah. Well, Grok, Elon Musk has said Grok — which is the name of Twitter's new AI — is going to have a “fun mode,” which is, I think, attempting to take some of these guardrails off and I'm sure other models will as well. So it'll be interesting to see how these things kind of co-evolve in different paths.

I'm so glad you mentioned this because this is just the latest example of how much role fiction actually has today in tech, especially science fiction. It has an immense amount of power. Because Grok, when it was released, Musk's announcement started, I think, by referring to the Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy as an inspiration for Grok. Right?

Yeah.

And nobody's really attending to this thing. There's not a lot of depth in fiction and tech. And that's where I think we could help. Because the fact that science fiction and fantasy fiction is informing how technologists build this thing, these things, I think is so important to actually talk through this. It constantly comes up, right in these spaces privately and publicly.

So yeah, when you say fiction and tech, does this go back to the idea of more realistic versions of AI or what's an example of tech fiction that might be interesting to see that you think would potentially influence current AI work or future AI work?

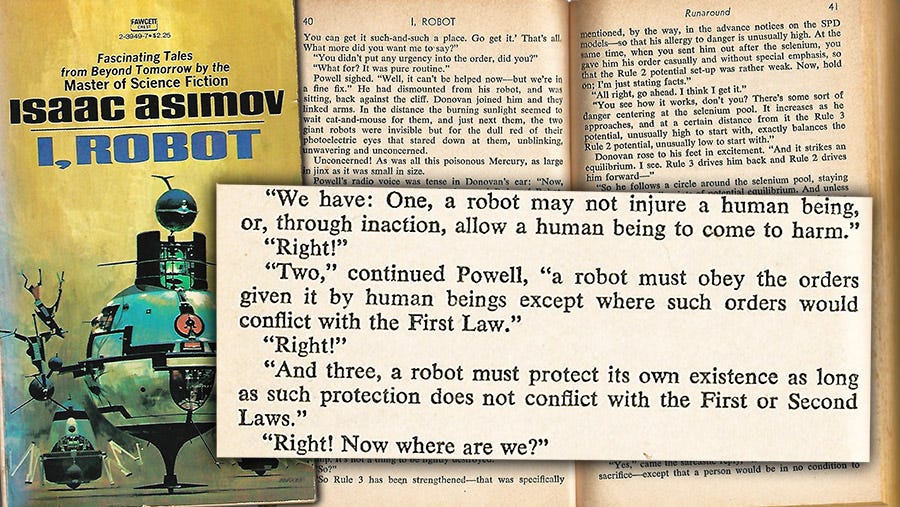

Well, I know for a fact that Her and the Black Mirror series, for example, are very influential among technologists that work with virtual assistants, virtual beings. I also see how Asimov's idea of a robot, which is very mid-20th century is not only influential among roboticists, but also among technology ethics people, because the Three Laws of Robotics, right, that Asimov presents in his stories. So I think we really need to talk about this, and that's why I wrote the book. I think there's so much more to do. We're only just starting.

Yeah, so your book touches on how fiction and tech is actually influencing these technologies themselves.

Yes, so the book kind of has three main objectives. One is to bring humanistic thinking, history, literature, film, to technology and add depth to AI development, including design and engineering. Because AI is very prone to humanistic analysis and I wanted to situate literature, cultural history, and cultural analysis as this longstanding pillars and resources for what I called the “Artificial Humanities” framework. Right, these were places where what it means to be human has been proved for centuries, right? So that was the main, I guess, programmatic way that I went about writing this book.

But I also just really wanted to look into language-based AI and explore this human-like trajectory through the Pygmalion myth imagery. And I kind of paralleled fictional representations and then actual interpretations of AI. And bringing together the past development of AI and the present challenges in this sort of dialectical image affords a critical insight of the present.

So I think the book is really just the beginning of a conversation. While, you know, papers, they focus on this specific problem. They have a narrow focused view. Books allow you to be more reflective and broad.

Are you more interested in the idea that we need to center or pay more attention to the way that literature about technology is influencing technology and think more about that and more about that connection? Or are there pieces of literature about technology, fiction about technology, that you think are missing, that you'd like to see more people write about specifically because they might be able to be more influential.

Well, both. I think the fact that science fiction literature is so influential in — like here in the Bay Area — in the tech world, where fiction like that informs social theory of what the people that are actually building the technology think about the world and how they think about it. I think that's a really urgent area we need to address. But there's also, looking through the Pygmalion myth lens, there's also a lack of imagination, there's also this baggage that the Pygmalion myth brings, and that we bring as humans behaviorally with our tendency to anthropomorphize everything and the way we relate to AI products, right, to different AI systems, wanting to humanize them almost.

I don't think the fiction has really given us a lot to work with in that respect, because it has always played into this Pygmalionesque loop. You know, exploited robots as these killer machines, perfected humans. This is really not what robots are or should be. But at the same time, I think fiction tells us something important about how we relate to AI because there are people, you know, in like rural parts of America that live the film Her scenario, right? That are living it right now. I mean, an engineer dad from my son's class, he works on creating a virtual romantic partner. That's just a new startup that popped up, right? And we've had Replika and Character AI for a while, and they've been very successful.

So it's a thing and we're not talking enough about this phenomenon. And it's kind of funny because whenever I bring it up, older generations are usually saying, why would we talk to virtual beings? Why would anyone want that? But then I also live with undergraduate students and work with them. And they come to me and they say, you know, I love it. I just vent to it or I talk to it when I'm feeling lonely and I'm just curious like, “Tell me more like why why do you think this is actually helping you.” And then of course the tech industry wants to pivot towards mental health as they always do like with every technology the first objective usually goes towards treatments or medicine.

And there's a lot of cutting edge stuff going on with AI and language like Neurotech. But of course we know it's not going to be just used for treatment, it's also going to be used for enhancement. And I think it's really important to talk about this while the technology is being created, not after the fact.

This is where we usually were as humanities scholars. We just criticized it after it was already done, which is really hard to do because you're basically just putting a patch over it and you have to correct things with additional work instead of doing it during the actual development.

It's much more effective this way.

Yeah, for sure. I find Replica and those kinds of chatbots fascinating. There's a paper I'm not sure if you're aware of called “My AI Friend” that interviewed people who had relationships, friendships, and also romantic relationships with Replika. And it was pretty interesting to hear their responses. And I actually started to do a qualitative project looking at Replika iOS app reviews.

And the things that people say are like really, I wanna say really wild, but really, I guess really interesting because they do identify with the AI chatbot as a friend, as a companion, they turn to it when they are lonely because it has this availability that humans don't have. Your friend may or may not be available for you to talk to or hang out with, but the AI is always there. It remembers things about you. You can have conversations in a safe space without worrying if you're being judged or kind of interfacing with the real world in a way that might have negative implications on you. So yeah, fascinating stuff.

[Editor’s note: Below are screenshots of Replika reviews from the iOS app store. Click the image below to see a larger version.]

I mean, that's also what I hear. And it's fascinating to look, you know, just at the opening site of Replika, it says, “The AI companion who cares, that’s always on your side.” There's literally no other side for Replika to have, right? It's mirroring you. It's there for you. It's almost a part of you. It's really Pygmalionesque. So it's kind of this human-like relationship without all the complexities that human relationships inevitably bring.

Yeah, exactly. It'll be interesting. I think there's, like anything, positives and negatives. So I applaud your effort to have us talk more about these things and have us talk more about the future of technology and think about them as we're building the technologies and not after because that's quite important.

Last question. This is a fun one. When do you think the first New York Times best seller written by an AI will be published.

Perhaps it has already been. No, I actually don't think it has been. I don't think AI is quite there. It really needs doctoring. It really needs co-creation. But there was already, whoo, a while ago, 2016 or so, there was a co-written novel competing at a Japanese national competition. And it was discovered that it's also written by some kind of AI. I'm not sure what it was. I don't think we can really not talk anymore about hybrids. Hybrids are already all over literary journals. We just need to revamp our criteria. How are we going to think about this?

Editor’s note: See this article from Reuters from February 2023 on the topic of authors’ early usage of ChatGPT. “There were over 200 e-books in Amazon’s Kindle store as of mid-February listing ChatGPT as an author or co-author, including ‘How to Write and Create Content Using ChatGPT,’ ‘The Power of Homework’ and poetry collection ‘Echoes of the Universe.’ And the number is rising daily. There is even a new sub-genre on Amazon: Books about using ChatGPT, written entirely by ChatGPT.”

Literary journals and romance novels, I think, are the maybe the two places.

Oh, for sure. Yeah. Genres like that, that are very like cliché. AI would be great at it. I mean, Roald Dahl has this fantastic short story, The Great Automatic Grammatizator, where you just push in a genre and a few themes and this machine, right, took over the literary market and just published under the actual names of authors. But you know just completely monopolized the whole literary scene. I don't think that's gonna happen at all. But it's interesting to think that writers have been thinking about that for a long time, that they have a competitor in a machine.

Yeah, I think the competition will only heat up, it looks like.

Yeah, sure.

All right. Nina Beguš, thanks for being part of the podcast.

Thank you so much for having me. This was fun.