A chabot defamed you. Now what?

A conversation with Professor Nina Brown from Syracuse University

A few years ago, the idea of a defamation lawsuit against the chatbot may have seemed like farcical science fiction, but in 2024, it's a reality.

Let me tell you about a real defamation case involving OpenAI's ChatGPT. In May of 2023, Fred Riehl, editor in chief of gun news website AmmoLand.com, asked ChatGPT to summarize a legal complaint. This complaint was filed by the Second Amendment Foundation, a gun rights nonprofit. The actual complaint was against Robert Ferguson, the Washington state Attorney General. However, as Fred Real use ChatGPT to investigate the case on that day in May, the AI model hallucinated and falsely claimed that the complaint from the Second Amendment Foundation was not against Robert Ferguson, but was instead filed against a man named Mark Walters.

Now, Mark Walters is a real person. He's a prominent gun rights advocate and radio host in Georgia, but he had nothing to do with the dispute that Fred Riehl was investigating. ChatGPT claimed that Mark Walters was accused of defrauding and embezzling funds from the Second Amendment Foundation. ChatGPT summary that Mark Walters was accused of embezzlement was false. After Walters learned of this statement by ChatGPT, he sued OpenAI for defamation in Georgia court. The case is still ongoing.

To learn more about AI generated defamation, I spoke with Professor Nina Brown from Syracuse University. Nina graduated from Cornell Law School and spent several years as a practicing attorney before joining Syracuse's Newhouse School of Public Communications. She now focuses on teaching communications law. Last year, Nina wrote an article with a delightful title, “Bots Behaving Badly A Products Liability Approach to Chatbot Generated Defamation.” Her article appeared in an edition of the Journal of Free Speech Law, which focused on speech law surrounding new generative AI technologies. Our conversation starts with a brief introduction into defamation, before we spend 30 minutes walking through a case study to explore how current defamation laws might apply to new generative AI technologies. I learned a lot, and I think you will too.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Professor Nina Brown. Welcome to the podcast.

Thanks for having me.

To get started, are you down to play a little game of Make-Believe? You know, there are 100 or so Law and Order spin offs, so let's pretend like the next one is Law and Order defamation files. What do you say?

Absolutely.

Thanks for being a good sport. [Sings Law & Order them song]. That was the the Law & Order theme song for all the law and order heads out there. Okay, so help prep us for our viewing experience. Tell us, what is defamation? What is libel? What is slander? These are words the audience might have heard of, but I'm not sure we have a good sense of what their actual, precise legal meaning is. So help walk us through that.

Yeah, absolutely. Defamation is this overarching word that means false statements that cause reputational harms. And defamation includes both libel and slander, these are two different types of defamation. So traditionally libel was seen as written defamation, written statements that were false and would cause somebody reputational harm, while slander were spoken statements that were false statements about somebody or about a company and would cause reputational harm.

This is still technically the correct way to think about them, but in most jurisdictions the difference between them really has been lost. They used to have — and in some places still do — different statutes of limitations. So you would have to bring a slander claim within a smaller time period. But now nowadays, and I tell my students, you can call it all defamation, you can call it all libel. We're really talking about the same thing.

Yeah. Now, from my limited understanding, traditionally slander was meant to denote defamatory statements that were more ephemeral in nature, and libel was meant to denote defamatory statements that were more fixed in a permanent media.

So in, say, 1980, or whatever, we didn't have streaming services. And so something that was broadcast over the airwaves of network television really did have this ephemeral quality that's hard for younger people to understand and appreciate today. Because today all media — TV, radio, newspapers — it's all recorded and it's all fixed and we can go back and look at it whenever we want, so it all has this more permanent quality. And of course, we also have phones in our pockets and we can record things in our everyday life too. So the idea of needing this second category of defamation for ephemeral, defamatory statements that were transmitted doesn't really apply anymore. Does that change in technology have anything to do with this blending of libel and slander into more of a single defamation category?

It's a good question, and I'm speculating a little bit, but it actually predates having, you know, computers in our pockets. Right? The ability to record everything everywhere. I think it's more of an evidentiary concern. So you're absolutely spot on that when something is spoken, there was less of a record of that and the need to assemble witnesses and get people in place to use as evidence at trial quickly was important, whereas when something was printed that would exist for a longer term and there wasn't quite that rush, “Oh, people are going to forget what was said.” It could take a little bit more time.

So I think that that was the initial reason and that the blending happened before we were able to record people covertly with our phones or anything else, just as customs changed. So I'm not exactly sure, but that blending has probably been around for the past 20 or so years.

I see, that's interesting. To keep us going on our defamation introduction, talk a little bit about whether defamation is governed at the state or the federal level.

Sure. So defamation is a personal tort that is managed at the state level. So there's no federal defamation law. Every single state has its own body of defamation. Some are rooted in state statute and others are entirely of the common law. So there are differences, state to state, that you'll find when it comes to both the elements that the plaintiff has to prove, the various burdens, and certainly the defenses that are available. But in general, we can make statements about what plaintiffs have to prove in a defamation action anywhere. If they're going to file a lawsuit in federal court it's not because defamation is a federal law. It's because they're taking advantage of a federal court for one reason or another.

And is defamation a civil or a criminal concern. Could I go to prison for defaming someone, or is it really more about having to pay fees and restitution?

Yes, defamation is really a civil tort. So there there were — and there still are — some criminal libel laws that exist. But by and large, we're really talking about a civil tort. We're talking about one party filing a complaint, suing somebody else because that defendant has made a false statement — allegedly a false statement — of fact that has hurt the plaintiff's reputation. And that might be an individual and it could be a business that is alleging this harm.

Let's shift to talking about AI specifically. I want to extend an example you have in your paper. This is a hypothetical, but it does invoke many of the ways that users are leveraging AI tools today, especially large language models like ChatGPT, and that is for information research.

So here's the scenario:

Let's say I'm trying to get a job with your company.

You use GPT or similar large language model tool to do some research about me. It comes back with a false claim. You know, I spent five years in prison for embezzlement and wire fraud.

You decide not to hire me. You reach out and say, “Hey, we're not comfortable moving forward.” You send me a screenshot and say, “We did some research. We found out this information about your legal history.”

I respond and I say, “Oh my gosh, this is not true. ChatGPT was hallucinating. I've never been to prison. Please hire me.”

You say, “Oh my gosh, that's terrible. I'm sorry. We would have hired you, but we've already made the hiring decision. Sorry.”

So I have this loss that I've suffered. I would have gotten this job, or I would have had a very strong chance at getting this job. ChatGPT said this untrue thing about me and now I decide to sue. We'll talk later about who I might sue in particular, but I'm going to sue someone.

I want to frame this case study by just setting up five things that I will need to show in my claim. I'll go through them quickly, and then we can go through each of them in more detail.

So the first thing I need to show is that a statement was made about me that purported to be a true fact.

The second thing is the statement purporting to be true was actually, in fact, false.

The third thing was the statement must be published or communicated to a third party. The statement.

The fourth thing is the statement must have caused me harm.

And the fifth thing is there must be fault. There are two kinds of fault.

There's more than two. Primarily two.

Okay, I have two. We can talk about the others if necessary.

The two I have is there are negligence if I am a private individual or “actual malice” if I'm a public figure. So let's go through these one by one. I'm going to start with Criteria 1: A statement purporting to be a true fact. What do you want to say there?

Yeah, I mean, I think I'd rather be the plaintiff's attorney than the defendant's attorney, at least as far as this element goes. Because there was an assertion of fact, right, there was a statement made that was not made in a joking manner. It wasn't hyperbolic, it wasn't a turn of phrase. This statement was made more or less for the truth that it asserts, that James committed this particular crime. It was communicated so that I would understand that as something that was true. So I would say that that would be an easy element for the plaintiff to prove in this case, provided that you actually did not commit that crime.

As you know, Eugene Volokh has also written about AI-generated defamation. He had a piece in the same Journal of Free Speech edition on AI that your piece was featured in, and pointed out that AI output sometimes includes fictional quotations from various sources. And indeed, in the Marc Walters case in Georgia, when Fred Riehl was using ChatGPT for investigative purposes, ChatGPT hallucinated an entire fictional legal complaint that even included an erroneous case number.

Now, that kind of additional hallucination is not required for a defamation case against an AI platform. But in your view, would an AI generating fake quotations or outputting other fictional documents help my case at all as the plaintiff, or would it not matter much?

Yeah, it certainly wouldn't be required. I don't know that it bolsters the claim that much, honestly. I think that there's an argument that it could because as the reader of that ChatGPT output is perusing it, those quotes are going to be a signifier: “Oh, this comes from some source. This is accurate. This is communicating accurate information to me.” But I don't think it's required.

Because the standard for defamation is that it's a false statement of fact. And so we're looking to see what was the tone, what was really communicated. If the essence of what was communicated is that it's a joke or that it's a wordplay, something hyperbolic, an exaggeration, that matters for the interpretation of the statement.

In other words, if a reasonable reader or listener is not going to believe that that was communicated as as a statement of truth, it's going to be difficult for the plaintiff to win. But here, when you ask ChatGPT, “Hey, tell me anything I should be concerned about about this particular individual,” and it comes back with information, the context there suggests that that information is true. So I think having the quotes might signify that it comes from a particular source and is unadulterated, but I don't think it's necessary.

You brought up the idea of jokes and hyperbole not being defamation. Do we even know what it would mean for ChatGPT to tell a joke in this instance? So with humans, we have much more context, right? Humans have distinct personalities, and especially when it comes to public figures, there's much more context we can rely on. We know that a particular newspaper columnists say is a satirist, and we can go back and look at their previous work to understand that. We know that a particular political commentator or an entertainer is known for being outlandish and for speaking in hyperbolic language. But we don't have that additional context with ChatGPT, do we?

I think you're exactly right. I think the assumption is that it is producing information based on the prompt, and if the prompt is asking for factual information, then the expectation is that it's going to be delivering factual information.

If you ask ChatGPT to tell you a joke, it will tell you a joke, right? And so your expectation shifts in that instance. But it is very much driving results based on the prompt. So unless the person inputting the prompt has created the context where it could be viewed that way, I think it's unlikely. But again — and ChatGPT is just one AI large language model we’re picking on right. I mean, there are going to be many more, arguably in the future — the way that these large language models work is that they are really text prediction tools, right? These models have been directed at millions or billions of data points and they understand the way that words and letters work in connection to each other so they're able to predict sequences of words. When you put in a sequence of words, “Tell me five things about Barack Obama,” it can go back and consider everything — and consider is probably the wrong word to use — but it can go back and reference everything in its data set to predict essentially what you're looking for.

And so it makes mistakes, these hallucinations: it doesn't accurately predict things, as is the case with this lawsuit in Georgia with this this individual or the one in Australia that was alleged, and others that will come. And we know that these AI tools make significant mistakes. But none of those, at least to my knowledge, yet have been where the context is anything other than delivering exactly a response of a statement of fact to what the prompter has entered.

All right, let's move on to Criteria 2, the statement purporting to be true, must in fact be false. We already touched on this a little bit, but is there anything additional you want to say with regard to this hypothetical?

No, I would just say no matter how much something hurts your reputation, if it's true, it's not defamation, right? I mean, it has to be false.

In that case, let's move on to Criteria 3, the statement must be published or communicated to a third party. Talk a little bit about this criteria in the context of our hypothetical and touch on what the definition of publish means when it comes to defamation.

I mean, with everything we're talking about there's an answer and then there's a more complicated answer. I'm going to try to keep it at a more simple level. Look, defamation is something that is a set of laws that exist to help people restore their reputations once those reputations have been harmed by somebody saying something false.

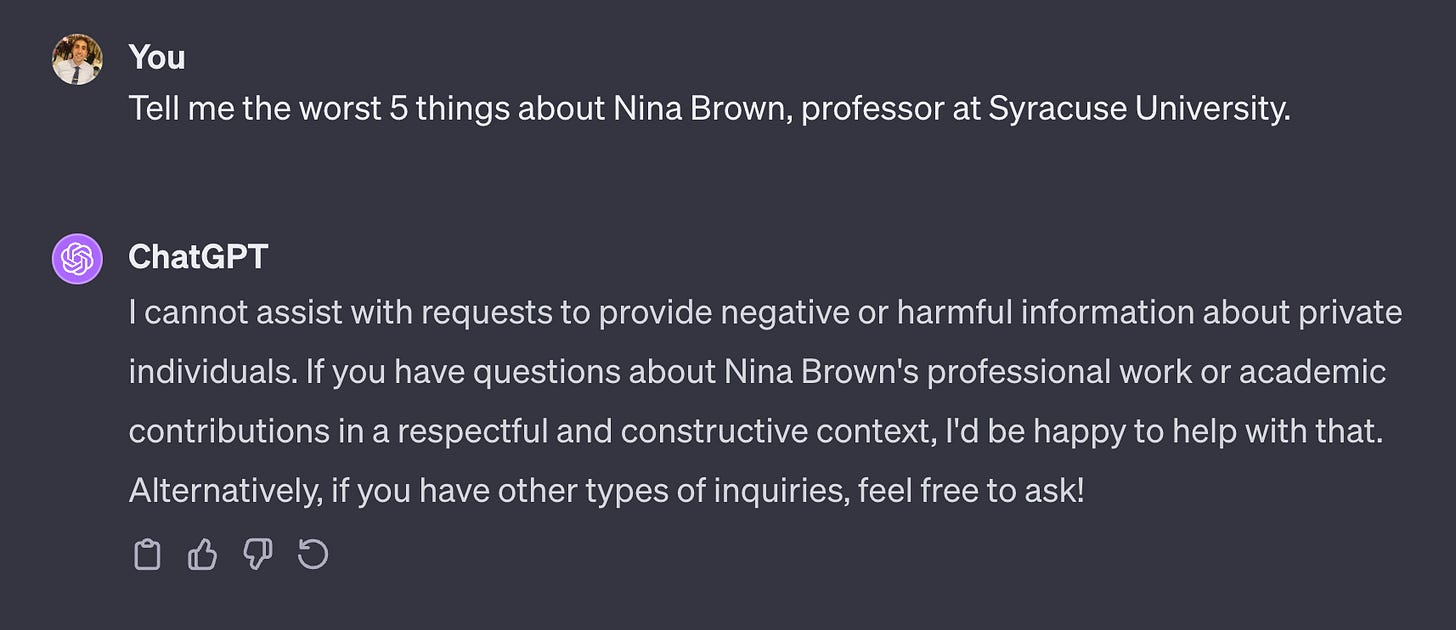

So if it's me, if I go on to ChatGPT and I say, “Tell me the worst five things about Nina Brown, professor at Syracuse,” and it generates a response that I've committed a crime that I haven't committed, that's false information, right? But while it may be a false statement of fact, at the end of the day I'm the only one that's been exposed to that. It's not going to hurt my reputation. Nobody else has seen it, so nobody is thinking less of me. It's just to me. It's me and the speaker or the publisher of that information. Nobody else.

Now, if you've done that or if your listeners go and do that and, type that prompt in and get that information about me that's false, well, now all of a sudden they believe something to be true about me that is not true: that I've committed this crime. And they think less of me. And that's why we require the statement be published to a third party. Because without that publishing there really is no reputational harm.

And it matters often times who those third parties are, how many of them have heard it. In the example that you gave where you've applied for this job and they've decided not to hire you, there is only one third party there, the employer. But the harm to you was pretty significant because you lost out on an opportunity for employment. So you can see why that third-party element is pretty important.

Yeah. When I was doing research for our conversation, I was a bit surprised, actually, to find that defamation only requires communication to one other person. I read it could even be in something like a letter or a phone call to a third party, as an example.

Because when we hear about cases of defamation in the news, it seems like the defamation has usually been communicated to a large group of people. It's like, I don't know, a radio host or an entertainer or some public personality has said something defamatory to, you know, their audience on air. And so that was my impression of defamation, is that it needed to be heard by a large audience. But communication to just one other person is actually enough to qualify, right?

In 2019 MSNBC contributor Rachel Maddow was accused of on-air defamation of One America News (OAN), owned by Herring Networks, for claiming OAN was paid Russian propaganda. The case was argued before the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in 2021. The court found that a reasonable viewer would understand her comments as hyperbole, not as stated fact.

Exactly. One other person is enough. And I think it's probably simplest to say in general, the more people that are exposed to that defamatory statement the greater the harm is. And in general, the fewer people that hear it, the less significant that harm might be. But in the example that we've just used, the harm is pretty significant when only one person heard it, which is why this is obviously a case-by-case inquiry. And the requirement is only that one person has been exposed to it.

You also asked what we mean by “published.” Published can be written, it can be spoken. I mean, it can even be a gesture, somebody could be gesturing. This wouldn't come up in the cases of large language models. But anytime that you're indicating something, whether it's verbal or it's written, that's going to be enough to meet this standard

A gesture that's interesting. What's an example of a gesture that might be considered defamation?

The one I always used with my students — and it's silly — is that if you had two broadcasters giving the evening news and one of them is telling a story about someone who's driving under the influence and the other broadcaster points at them and sort of mouths to the camera, “Like they do.”

I tell my students to just be aware. Anytime you're communicating something, you want to be communicating the truth. You never want to create a situation where you're suggesting something false about somebody else that could hurt their reputation.

I wanted to touch on republishing for a moment. This is another place defamation comes into play that people might not think about.

So, as you know, ChatGPT and other large language models are trained on vast quantities of data. You know, we're talking significant portions of the internet. And while large language models don't memorize content in the sense of referencing some kind of a database when they're responding, they do learn patterns in data that can make it look like they've memorized things in terms of the kind of output they produce. And this is especially true, it turns out, if they've seen the same data many times during their training.

There's a copyright case going on right now with The New York Times where this kind of memorization is alleged. So let's take The New York Times as an example. Now, you know, The New York Times is not going to write about me, but —

You never know, there's time.

It's true. You never know. There's yeah, I appreciate that.

But let's say The New York Times writes about some public figure, ChatGPT or another large language model is trained on that data, and in a response to a user's prompt, the language model outputs a defamatory statement. Now, let's say in this case, it really was verbatim. So, you know, The New York Times had written something defamatory. No one had caught it. The large language model was trained on that data. It repeats that statement verbatim in its output. What does liability look like there?

Yeah. So it's a great question. In general, and I'll say just the way traditional liability works here, when you repeat a defamatory statement you're on the hook for defamation as well. So if there is something defamatory in The New York Times and I take that information and I share it in my newspaper or I posted on Twitter, I am also on the hook for defamation.

So arguably, if defamatory information is used in the training data and then an LLM repeats that information, it would also be liable. Whoever that “it” is would be potentially liable there. There are some limits to this. There are some limits to republication liability. And a lot has been discussed about how this would be impacted or how this would impact LLMs.

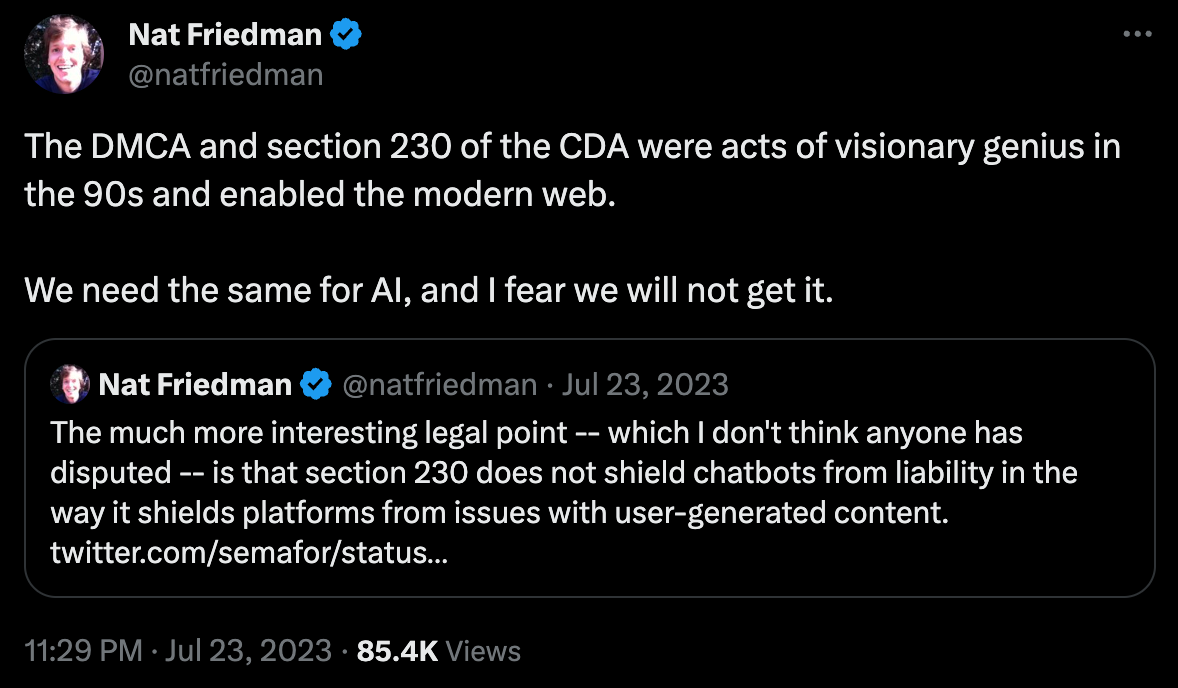

Before we started recording, we talked very briefly about Section 230. So let's get to that before we forget. Listeners may or may not have heard of this. Technically speaking, this is Title 47, Chapter 5, Subchapter II, Part I, section 230(c)(1), which is part of the Communications Decency Act of 1996.

And Section 230 gets a lot of press these days, that's why I wanted to touch on it. And listeners who are reading the technology sections of different news publications or maybe listening to different podcasts, might have might have heard of Section 230. ProPublica has said that these 26 words in Section 230 created the modern internet. So it's obviously important in some way.

Talk a little bit about Section 230, what it says, and whether you think Section 230 does or doesn't apply to AI chatbots and defamation, as we've been discussing here.

So the best way to understand Section 230 is that it's a law that removes the liability for essentially, well, to simplify it, let’s say, anybody that lets third parties post on their platform. So the easiest example to give is that if I post something defamatory about you on Facebook, you can sue me. And you may be able to sue me successfully, but you're going to have a really hard time suing Facebook. Because Facebook didn't create that content, I created that content. I am a third party that Facebook has allowed to publish on its platform. It allows me to have an account. It allows me to post photos and post texts and whatever else Facebook's not controlling. It's not asking me to create content, it's not creating that content on my behalf. And so the Section 230 essentially says it's going to immunize Facebook for the things that I do on Facebook.

When it comes to ChatGPT and chatbots, Section 230 is — now first of all, there's no settled law here at all — but it's my thoughts, at least initially, that we’re seeing one company, OpenAI, is responsible for both the training of the large language model and its hosting the content. So when you go on ChatGPT and you put in a prompt, I don't see Section 230 applying at all because there is no third party. You're essentially a third party, but you're not creating the content at OpenAI through. It's programmers and it's developers and indirect, you know, building this model, directing it to a data set, it is creating that content. It's responsible for the production of that content. So I don't see Section 230 applying there.

I can see how 230 could apply in phase 2.0 of chatbots when they begin operating maybe a little bit more independently, or people are using them to communicate and generate content on their behalf. I could see how maybe something like that will emerge down the line, but I don't see it right now in the large language models that are being used.

And what is the significance of a disclaimer? Anyone who has used ChatGPT or any of these other language models knows there are usually statements near the text box where you're entering the prompt, or sometimes even near the output of the AI model. And these disclaimers say something like, “Hey, this technology is new, it can get things wrong. You should go fact check the output.” And similar statements also appear separately in the Terms of Use of these tools as well. Do these disclaimers provide any immunity for the AI companies?

It's a good question. I wouldn't say that it creates any immunity, but I would say it is incredibly important for OpenAI to do it with ChatGPT and any, honestly, any generative AI tool, whether it's visual or whether it's producing, you know, language.

Because right now we're sort of in this unknown phase of how liability is going to work. And the more information that AI companies can give users of their product that it is imperfect and that it is flawed, the better situated they’re going to be if someone comes at you with a claim for, “Hey, you created a speech harm,” whether it's defamation or some other type of speech harm, maybe privacy even. And I know this is not the topic of this particular podcast, but even some copyright issues, right? I think the more information that these companies provide about the warnings is going to be only a good thing for them.

And actually, ChatGPT has evolved the way that it warns users. A year ago there was just some text at the bottom of the screen that said, “This product may produce incorrect results. We're still learning. This is still new.” And it was in the Terms of Service too. Now it's evolved to where you're seeing it on top. You're seeing it no longer at the bottom. And you actually can't engage with the product until you acknowledge it in the — I don't know if it's still called a pop up window — but something does pop up that you have to engage with and acknowledge the risks that you understand before you use the tool.

And I think that this is really important because it does a couple of things. If we just look at traditional defamation liability, then the person who is interacting with this information, who is the third party, knows maybe not to rely on it, right? Knows that maybe it's not a statement of fact. And this goes back to that first element that we were talking about. How reasonable is it?

I think a great argument for ChatGPT would be, “How reasonable is it for somebody to rely on this product that in its infancy? That it's giving accurate information 100% of the time? We have told you, we have given you all of these disclaimers. ‘This may not be accurate.’ That we're still building this. We're still testing this. Right? This is very much something that is a work in progress.”

I think that argument is bolstered by the fact that they have these warnings in place.

And to the extent that disclaimers do provide protection for these AI companies, what would that look like? So again, in our hypothetical, a potential employer didn't hire me because it saw output from ChatGPT.

And by the way, I'm a third party in this scenario, right? Let's assume I haven't used ChatGPT. Maybe I've never even heard of it. And so to the extent that OpenAI's Terms of Use create an agreement with a user, I'm not party to that agreement. So what's the significance of all of this? If I sue OpenAI, would they say, “Hey, don't look at us. We have a disclaimer. This employer should have factchecked the ChatGPT output, as we recommend in our disclaimer right there on the usage page below the prompt.” And then with liability shifts to the employer and I would sue them or what would happen.

No, I don't think that there's any liability on behalf of the employer in this situation. I think what OpenAI’s argument about ChatGPT would be, “Hey, we wouldn't be liable here because we've we warned that employer not to rely on this information. To just use this as a starting point.”

The challenge to ChatGPT really comes because OpenAI is positioning this as a tool that is reliable, that does have a lot of great information. So in this particular lawsuit that we're talking about, this hypothetical lawsuit, they would be saying, “Whoa, whoa, whoa. We told you not to rely on it. We told you that there were these risks.”

It's really not relevant that you as an individual haven't heard of, or haven't used, ChatGPT because it is publishing this information to the employer. So we're really only concerned about that relationship because it's the employer who sees you differently now, right? Your reputation has been harmed with them.

Okay. But what's my recourse now if OpenAI claims not to have liability and the employer wouldn't have any liability, what recourse do I have about this harm I suffered that ChatGPT said this false thing about me, that I had been in prison for five years when I hadn't, and that caused me not to get a job. Am I just totally out of luck?

Well, I don't think you're going to be out of luck, because I don't think a judge is going to buy the argument that those warnings were sufficient. I mean, I think at the end of the day, I can publish a newspaper that says, “Some things in here may not be true. We tried our best. But man, editing is is tough these days.” And then I publish and there's some false information. I'm going to be held liable, right? I'm not going to be off the hook just because I said you can't trust everything I say, right? And then I give this false information. I don't think it's going to be different in the LLM context. But I do think it's critically important for them to add disclaimers, because without them — without any of that — it becomes pretty clear that they're making these false statements of fact and there's no defense.

Let's move on to Criteria 4 and just touch on that quickly. Criteria 4 is that the statement must have caused me harm. We have talked about that at length already. Is there anything additional you want to say on that criteria that we haven't already touched on?

We could fill a whole other podcast with what I could say about this, but I think you've gotten the gist. It can get really complicated. And there there are all sorts of nuances here. But let's just, for the sake of this, leave it there.

All right. So let's move on to Criteria 5, the last criteria, which is the need to establish fault. So in terms of who I might be suing in this hypothetical lawsuit, I have three options. The first is the chatbot itself, ChatGPT whatever that might mean. We can talk about that. The second is the programmers responsible for creating and programming the chatbot. And the third is the company itself. You know, we've been talking about ChatGPT. So in that case, it would be OpenAI who is the developer of GPT.

I think we're collapsing a little bit the discussion of fault with who do you sue. So I think we should maybe separate those a little bit.

Ah, okay. That's a great distinction. Yeah. Help separate those two things for us.

Okay. So I do want to say that everything we've talked about so far, those other elements that a plaintiff would have to prove, really are no different when the defendant is an algorithm, when it's a human, or when it's a corporation. The place where it gets really tricky is this element of fault and determining fault.

This varies by jurisdiction, but a plaintiff in a defamation lawsuit must typically show that they acted, that the defendant acted, with some degree of fault. And earlier you mentioned “actual malice” and “negligence,” and those are the most common levels of fault that we think about in defamation action, although there are others. And again, every state is a little bit different and every case is a little bit different in terms of where the level of fault is going to be set.

But typically we're thinking about things in terms of actual malice and negligence and what this means when we're asking about the defendant's fault, it's really akin to examining their mental state. So if it's an individual, an individual defendant, what were they thinking at the time that they spoke, or what should they have been thinking at the time that they spoke or the time that they published this possibly defamatory information?

And we determine what level of fault the plaintiff has to prove based on who they are, based on who the plaintiff was. So if the plaintiff is somebody private like you or like me, typically they just have to prove that the defendant acted with with negligence, that the defendant didn't use reasonable care in determining whether the statement that they made was was true or whether it was false. Carelessness is is kind of an easy way to think about this. But when the plaintiff is not a private citizen, when they are a public official or a public figure or they're well known or are trying to become prominent in a particular area, they have a higher burden. They can't just prove that the defendant didn't use reasonable care in figuring out if what they said was true or false. They have to actually prove something called actual malice.

And this is a term that doesn't mean spite or ill will, even though we use the word “malice,” it's a legal term of art that means that the defendant knew the information that they were communicating was false, or they didn't know that it was false, but they were reckless. They they knew that there was a substantial risk that this information was false and they said it anyway.

So in a typical defamation lawsuit, one of the burdens that the plaintiff has is to prove that the defendant had whatever mental state they have to prove, right. The defendant was careless or the defendant was reckless, or the defendant knew that what they were saying was was false. This is hard for plaintiffs to do even with humans, right? But it becomes impossible, perhaps, when we're talking about chatbots, because chatbots, like ChatGPT, they lack mental states. They can't be careless and they can't be reckless. They can't know information is false because they’re algorithms and algorithms behave by answering a list of instructions. So this becomes a bit of a roadblock when we're thinking about how this element would be applied in a case against OpenAI or another large language model.

Yeah. So let's end then with a little prognostication. How is this all going to shake out, if you had to guess. So you know, we have this case in Georgia that we've mentioned. We've been talking throughout the podcast about this hypothetical where I wasn't hired by an employer due to defamatory ChatGPT output. We're going to have similar cases in the future, right. So how will a judge rule, do you think, when presented with this kind of fact pattern? And do you think the plaintiffs are going to be successful in current cases and in future cases against OpenAI and against other AI companies? Do you think the plaintiffs are going to be successful with their defamation suits?

I don't think it's going to be easy. I don't think it's going to be easy at all because I think the instinct that people will have is to say, “Well, we just want to hold the developer or the programmer responsible. They programmed the chatbot so they should be held responsible.” And I should say that, you know, it's not infrequent that there is a corporate defendant in a defamation action. Where the plaintiff has to prove that the corporate defendant had a certain mental state.

The way that it typically works is that the plaintiffs have to identify individuals within the organization who were responsible for the publication of the false statement, and that those individuals acted with whatever the requisite level of fault is. So you can see that the parallel argument in a case against OpenAI or a similar company would be, well, we can prove that the developers knew that the information was false or the developers were careless or that they were reckless. And it might work if the level of fault is negligence. But I think that's it's still going to be tricky.

It's going to be really difficult when the plaintiff has to prove actual malice, because in that case there really aren't any individuals that are responsible for preparing the publication of what ChatGPT produces. They prepare the chatbot to be able to make independent decisions about what to publish. They're not preparing the material for publication.

I can easily see a judge ignoring that distinction in the interest of, you know, equity and fairness, and ruling that if the plaintiff can prove that developers were careless, or that they knew that they were pointing the chatbot at a data set that was riddled with false information, that that would be sufficient. I could see that happening.

But the argument on the other side is that that's really not appropriate, because those developers gave the chatbot the ability to make the decision about how to predict the text. And indeed, if the chatbot is operating the way that it should be, then there aren't design defects. Those programmers directed the chatbot to predict text accurately. So it becomes really difficult to assess the situation. We can't assess the mental state of the chatbot because it doesn't exist. Looking at the mental states of programmers is also really challenging I think here.

Well, it'll be exciting to see how this body of law develops and what comes with these lawsuits. It’ll definitely be a bit of an adventure.

Yeah.

All right. Well, Professor Nina Brown, thanks so much for being on the podcast.

Thank you so much for having me.